Arts & Culture June-July 2025

A room of her own

Exhibit traces British women artists’ role in 20th century social change

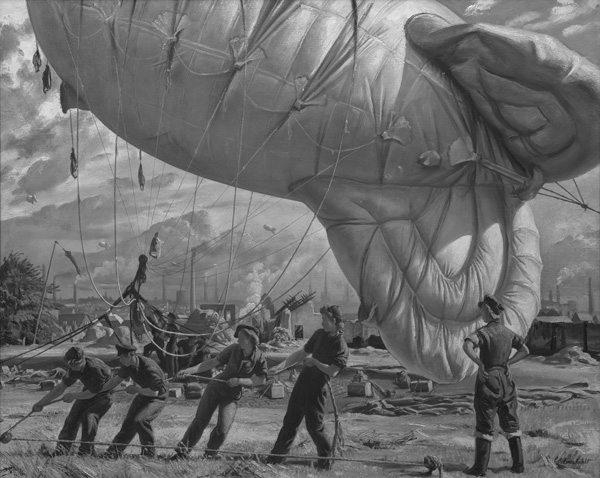

Dame Laura Knight’s “A Balloon Site, Coventry” (1943) is among the works gathered for the Clark Art Institute’s new exhibit “A Room of Her Own: Women Artist-Activists in Britain, 1875-1945,” which opens June 13. Imperial War Museums/courtesy of Clark Art Institute

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

WILLIAMSTOWN, Mass.

Thousands of women are marching in London. More than 10,000 have come in from across the country and beyond. And they carry a thousand banners celebrating women through time — Vashti, Boudica, George Eliot, Joan of Arc, the American suffragist and abolitionist Lucy Stone.

Many of those bright banners come from one artist — glass sculptor Mary Lowndes, co-founder of the Artists’ Suffrage League.

On June 13, 1908, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies was fighting for the right to vote. The London Museum recalls the procession as a “glorious spectacle,” bright with the gowns of doctors and graduates and banners blowing, “each different, each wrought in gorgeous colour and rich materials.” Lowndes’ daughter carried an image of the Swedish opera singer Jenny Lind.

The Sunday Times saw strength, the museum says. The newspaper described the rally as “the Valhalla of womanhood,” a vista of colors that resembled a Medieval army, “marching out with waving gonfalons to certain victory.”

And now, more than a century later, the bright minds in the lead and at the center of the movement are gathering at the Clark Art Institute. Lowndes and her friends, her lifelong love and fellow artists, come together in the museum’s summer show, “A Room of Her Own: Women Artist-Activists in Britain, 1875-1945.”

Through 87 paintings, drawings, prints, stained glass, fiber art and more, the museum will honor women creating change, said exhibition curator Alexis Goodin, associate curator at the Clark.

Goodin sees these artists as making spaces for curiosity and play — creating, teaching and learning, growing community, marching for women’s suffrage, protesting World War I.

These themes emerge from kernels in the museum’s collection, she said in a conversation over Zoom as she prepared for the show’s opening on June 13-14.

Goodin had been considering work that has recently come to the museum: Anna Alma-Tadema’s watercolors and Evelyn De Morgan’s painting and drawings. And then her scope widened to encompass the artist Vanessa Bell, the sister of Virginia Woolf and a central member of the Bloomsbury Group, an early 20th century community of artists and writers in London.

“So I had this very modern sensibility,” Goodin recalled, “a very different type of art that I needed to link with the Anna Alma-Tadema, which is so highly detailed and very rigorous in its application of careful glazes of watercolor, and then the very symbolic and strange and also very beautifully detailed Evelyn De Morgan work.”

The Bloomsbury Group became her way in, Goodin said. She found a throughline in Virginia Woolf’s writing about how women need time and space and independence to grow their creative lives.

In her 1929 essay “A Room of One’s Own,” Woolf argues in clean, clear lines that for women to write fiction or to make art — for women live fully in minds and bodies and dreams of their own — they need freedom to think and breathe and to create.

Pushing against social constraints

Living in Cornwall at England’s southwestern tip, Laura Knight would bike to Lamorna Cove and sketch on the rocks of the coastline.

She reached higher, making full-sized studies for a painting she called “Daughters of the Sun.”

“I climbed along the cliff-edge and over slippery rocks every day,” she wrote, “carrying six-foot canvases on my head.”

Knight’s energy radiated among the people close to her. Her friend Mornie Birch described her in Elizabeth Knowles’ study, “Laura Knight in Open Air,” in the Clark library, as “supple in her movements, dancing one minute, gesturing the next.” She would shimmy as she walked, swinging.

Resting for a moment, Knight “would open her eyes and start drawing again, using anything that came to hand, old envelopes, invoices, anything. She was irrepressible.”

Many women in her day pushed back against strong currents of repression. In Woolf’s era, against social pressure, some women artists were making choices about what home meant to them, Goodin said.

They were making choices about family, whom they wanted close to them, how they defined home, how they wanted to live — and how to make home a place where they could work and play and rest and love.

“Sometimes home was where you set up your studio,” Goodin said, “and your bedroom or your living room doubled as your workspace.”

With room to explore, Goodin sees these artists expanding their practices. When Anna Alma-Tadema had her own studio at home, her painting changed definably. She had been set up in corners of living rooms or outside by the carriage house, painting interiors. In her own studio, she started painting portraits.

“She paints friends and herself,” Goodin said. “She moves on to the landscape. And I think having her own space gave her the freedom to actively pursue a professional career.”

De Morgan too grew and thrived in her own space. With her studio, she could submit many different works to annual exhibitions and later create her own exhibition spaces.

“And so instead of seeing it as a limiting or traditional space,” Goodin said, “where women were ascribed specific roles as family members, whether they were the dutiful daughter or a supportive wife or a mother, I think of the home as a space of possibility.”

Learning from like minds

Women who wanted to write or paint or sculpt or shape colored glass needed more than room in which to work. They needed resources — paint or kiln or clay – and they needed access to public spaces and to arts and educational institutions.

Where could they study? Could they find teachers and mentors and artists in the field? Could they walk and sketch in the streets? The Clark’s sweeping show of women in Paris at the same era showed how hard it could be for women even to have a cup of coffee in a cafe, let alone to travel and to see the work of other artists.

Goodin explores the space of art school and places to meet artists, to find guidance and friendship, to talk with like minds. Women artists banded together and formed their own art societies, she said. They pooled their resources outside of formal academies.

She also recognizes the Slade School of Fine Art, which opened in London in 1871 and was unique in that from the beginning, the school admitted women. But its women art students still faced limitations in what the school allowed them to draw — most notably, elements as close as their skin.

An artist needs to understand how to draw the human body, Goodin said. To represent people, they need to know proportion, the movement and flex of muscle and the shape of bone, the texture and shadow and expression.

One of the greatest sources of resistance to women artists, she said, was the idea that they would draw models from life.

Knight wrote that when the men in her art school went to sketch the live model, she was sent to the cast room to draw from plaster. And because she never had the chance to sketch the body in living form, Goodin said, all of Knight’s early work was very wooden and stiff; it took her years to learn on her own.

The Slade later set up a separate studio so that women models could pose for women students, Goodin said.

“And men also posed,” she said. “We have a wonderful sketch by Evelyn De Morgan coming to us from a private collection. But in the case of male models, they were always draped.”

Outside of school, women artists found ways to experiment. Friends modeled for one another. Nina Hamnet would model for other artists, and friends and peers posed for her.

Knight had the resources to bring models from London to Cornwall for “Daughters of the Sun.” But she still faced risk and gossip, Goodin said. Even on the high cliffs around her rocky coves, she could rarely find privacy. Cornwall had locals and tourists enough to see and comment.

Spaces for art and activism

Artists who needed more than pen and ink faced a steeper climb. Once out of school, they needed materials.

Goodin expressed admiration for Lowndes for having the passion and the energy to find teachers for glasswork and to partner with glass artists — and eventually to gather funds and architects to build a studio for glassmaking.

Lowndes co-founded the Glass House in Fulham in West London. Her studio, Goodin said, became important for women glassmakers — and for some independent men who didn’t want to join an established company. If they wanted to design glass, artists could come into this space, rent a studio and get help from different technical experts for every step, from cutting the glass to fixing it with lead.

“It was a really powerful thing for Lowndes and her career, and also for women who followed,” Goodin said. “A number of important stained-glass makers accomplished work through the help of this cooperative studio.”

Studios can become gathering spaces — places to talk with friends and other artists, and also as centers for organizing, she added. In these spaces, people begin to talk to each other and gain strength in community.

Louise Jopling founded a studio and an art school, teaching her craft and welcoming, nurturing and challenging students to work with each other. And she also rented this space to suffrage groups as a place to gather and discuss.

Sometimes activism can be subtle, Goodin said. Although people marched in public displays where they were asking for suffrage, women in the Bloomsbury Group’s era also made choices in their everyday lives that shaped revolutionary change — choices about “who you live with, who your partner is, how you live, whether you live with others who are interested in the art world, or you have a romantic partner, or you decide not to have children.

“I thread throughout the exhibition these activism moments,” she said. “And it might not be completely formal and public, but in the way that they lived their lives, they were activists for change and making possibility or possible new modes of living.”

Artists in this show open to experiences of partnership and love, she said, with warm curiosity and strength and complexity. Some of the women in the show openly loved women — May Morris and Mary Loeb, Nan Hudson and Ethel Sands.

Lowndes and her lifelong love and partner, Barbara Forbes, lived and worked together for much of their lives, and they held leading roles in the Artists’ Suffrage League, a group of artists, including May Morris and Marianne Stokes, who created artwork and posters and postcards to support voting rights for women both in Britain and America.

Many of Lowndes’ banners are still in the collection of the Women’s Library at the London School of Economics, and also at the Museum of London, Goodin said. She has not tried to borrow these items, because the materials are fragile, and the banners are so rare and precious that they’re very rarely lent. But she has photographs in the exhibition catalog of the 1908 suffrage procession parading through the streets.

On the western front

In the later span of this show, women increasingly came out into the world to protest, to work and to fill an expanding ecosystem of roles. With the start of World War I, Goodin said, women were working on land army projects, in factories, and on the front lines.

Women were driving ambulances in the trenches, and Red Cross nurses tended wounded and dying men within range of the shells. On the home front, women were working at munitions factories and running farms, estates, businesses when men were called to the front.

The show includes work by Knight, and by Anna Airy and Lucy Kemp Welch, documenting war. Welch showed the Women’s Land Army in the Ladies Army Remount Depot from 1918, training horses that were going to be sent to the front, Goodin said. Knight, painting in World War II, showed the Royal Air Force and women’s auxiliary Air Force.

Anna Airy showed women working in munitions factories in World War I. As many as 1 million women did, according to the Imperial War Museum, filling shells with explosive TNT. The work was dangerous; mishandling this material could cause entire factories to explode.

So in World War I, women could die for their country, but they still could not vote. Women’s suffrage would not arrive in England until passage of the Representation of the People Act in 1918, two years before ratification of the 19th Amendment gave women across the United States the right to vote. Even then, the franchise in Britain included only women over age 30 until 1928, when it was extended to all men and women over 21.