Arts & Culture February-March 2025

Dreamlike images in black and white

Hudson Hall show gathers area artist Michel Goldberg’s monotypes

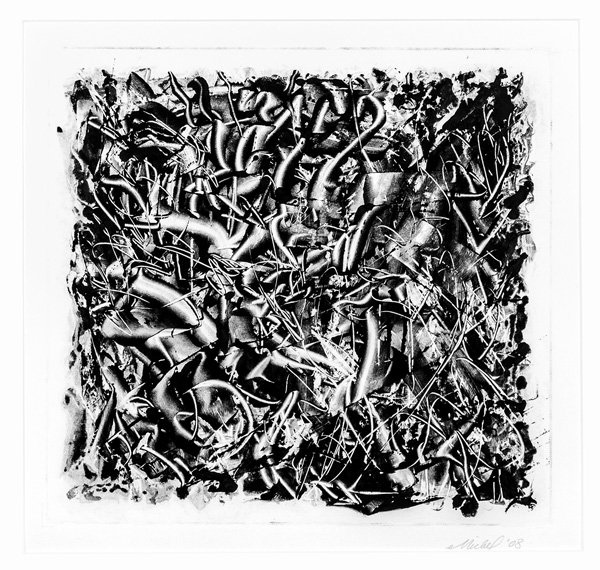

Michel Goldberg’s “After Bertoldo di Giovanni 1” is among the monotypes on view in the artist’s new solo exhibition at Hudson Hall. Courtesy photo

By JOHN TOWNES

Contributing writer

HUDSON, N.Y.

The mysterious monotypes of the Hudson Valley artist Michel Goldberg are the focus of a new exhibit that runs through March 23 at Hudson Hall.

Goldberg, who lives in the Greene County hamlet of Freehold, has assembled a variety of works from throughout his career for the solo show, which opened Feb. 1. Although it presents mainly monotypes, the exhibit also includes other media including sculpture.

Monotyping is a form of printmaking that is believed to have developed in the 1600s. The Italian artist Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione (1609-64) and the English poet and artist William Blake (1757-1827) were among the early creators of monotypes.

Although the technique faded from popularity for a time, it was rediscovered in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Later artists who produced monotypes include Degas, Pissarro, Gauguin and Chagall, and use of the medium is continued by contemporary artists such as Goldberg, who is known for his mastery of the monotype process.

To produce a monotype, the artist draws or paints an image on a smooth, non-absorbent surface such as copper, zinc or glass. Goldberg said he uses Plexiglas primarily.

The plate is placed in a bed on a special press with a large heavy roller. Paper is placed on the plate, ink is applied, and the cylinder is rolled over the plate under high pressure, which makes an impression of the artwork on the paper. Monotypes also can be created by inking an entire surface and then, using brushes or rags, removing the ink.

Monotyping produces a unique print, or monotype. Most of the ink is removed during the initial pressing.

Goldberg noted that the process allows only one original to be made, although a variable second print known as a “ghost image” is sometimes possible.

“One of its characteristics is that each print is one of a kind,” he said.

It is possible to use differing techniques and equipment. The press can be large. Goldberg works on a press he commissioned that has a 30-inch-by-60-inch bed in a frame and a large metal cylinder. He frequently produces works that are on 30-inch-by-40-inch paper.

“But it can also be done with a smaller and simpler setup, using a regular rolling pin,” he said.

Goldberg said the process of printing on a press is physically demanding and exacting.

“It’s very physical and takes a lot of strength to produce a large print,” he said.

Graphic design to fine art

Goldberg was born in Paris and came to the United States in 1948, when he was 8. After graduating from Pratt Institute, he worked in graphic and exhibition design for Will Burtin, a prominent designer in the mid-20th century, and at the fine-art printing firm Clarke & Way, which was also known as The Thistle Press.

He also taught graphic design and visual communications at Pratt Institute and had his own graphic design firm in New York City.

But he eventually left behind commercial graphic design to focus on fine art. Goldberg produces drawings and sculpture, but his primary medium is monotype printmaking. His work has been exhibited in various shows including a survey of contemporary monotypes and monoprints last year at the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild in Woodstock, N.Y.

Goldberg said the medium of monotype appeals to him for its physical qualities and an unpredictable aspect. In addition to the different forms and methods that can be used, he said, the results are affected by several factors including the qualities of the paper and inks.

“One of the attractions of monotype is that you can’t guarantee an exact reproduction of the image,” he said. “There are many variables, and you can’t predict exactly what the final print will look like. That gives it an unknown mystical quality, which I find exciting.”

The majority of his work is black and white. He noted that one of his techniques is to also place three-dimensional objects on the plate.

“That gives the print depth so it’s not just flat ink,” he said.

He said his work is essentially an abstract expressionist style.

“My influences and inspirations are varied,” he said. “My studio is on a large property in the woods, and much of my work is influenced by nature.”

While abstract, his depictions convey the sense of fields, woods and other sites. Often they are highly detailed, with stones, twigs and decaying leaves he finds adding new forms and textures. Each of his pieces invites viewers to linger and explore the intricate details, from delicate brushstrokes to layered textures.

Another source of inspiration is music.

“I love music and try to convey the feelings I have listening to that,” Goldberg said.

Art critic and curator Dominique Nahas described Goldberg’s work in an essay that appears on Goldberg’s website (michelgoldbergart.com).

Goldberg “somehow manages to magicalize each of his surfaces in different ways, transmuting them, causing a cascade of sensations to emanate from his prints,” Nahas wrote. “He can create imprinted surfaces that are evanescent and smoke-like or water-like to the perceptible world that it really feels like vapor, smoke, cloud-like wisps, water, something so fleeting, intangible, something that slips away from your senses.

“Goldberg treats each surface with such radical intensity that his artworks are open invitations for the eye to dwell, circulate and to linger with each work. His pictorial surfaces are alive with activity,” he added.

Goldberg sees his work as an ongoing exploration in which the process of creating is as important as the result.

“You are constantly learning and discovering,” he said. “Real art is a search. That’s what it is ultimately about. It has no beginning and no end. Hopefully, what you discover along the way will live on.”

Michel Goldberg’s solo exhibition opens Feb. 1 and will remain on view until March 23 at Hudson Hall, the historic opera house at 327 Warren St. in Hudson, N.Y. Visit hudsonhall.org for more information.