Arts & Culture September 2022

Picturing a path to freedom and equality

Rockwell Museum show explores race in illustrations past and present

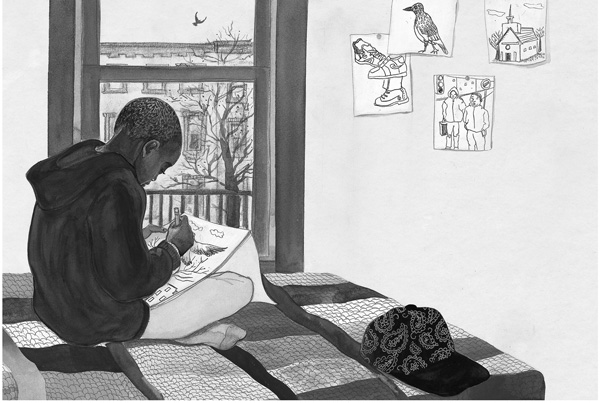

Shadra Strickland’s “Today a bird came to my window” is among the works included in a Norman Rockwell Museum show that explores how people of color have been depicted in images across 400 years of American history.Courtesy Norman Rockwell Museum

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

STOCKBRIDGE, Mass.

A woman listens to music with her eyes closed. Sunlight touches her shoulder, and silver rings gleam in her dark braids like new moons.

Nearby a boy sits cross-legged, sketching a bird on a branch outside his city window, and a man and woman are walking casually close together — he with a towel or T-shirt slung over his shoulder, and she in a long golden sun dress. A song plays around them, Nina Simone singing “Young, Gifted and Black.”

They gather together at the height of “Imprinted: Illustrating Race,” the summer show at the Norman Rockwell Museum, an upwelling of contemporary artists in an exhibit that considers representation of people of color in America across more than 400 years.

Noa Denmon’s affirming image of a woman at rest, confident and dreaming, joins Hollis King’s “Couple in Harlem” and Shadra Strickland’s “Today a bird came to my window,” and they share the galleries with images, past and present, that reveal histories of pain and strength, traumas and activism, stories of slavery, emancipation, the civil rights movement and more.

“People who have gone to see the show have had various emotions, from lows to highs,” said guest curator Robyn Phillips-Pendleton. “And we said that’s exactly the point. Why are there museums if you can’t evoke those kinds of emotions? That’s what stories are for.”

Phillips-Pendleton, an artist and illustrator herself and professor of visual communications at the University of Delaware, has co-curated this broad exhibit with Stephanie Plunkett, the museum’s deputy director and chief curator, based on many years of research. The show runs through Oct. 30 and will be the focus of an online symposium with multiple guest speakers on Sept. 23 and 24. (For details, visit the museum’s website at nrm.org.)

Shaping stories across time

In preparing this show, the curators worked together through the pandemic with a community of artists and advisers, some with connections to the Rockwell: Rudy Gutierrez, whose brilliantly colorful artwork appeared here in a group show encouraging action around the last election; Kadir Nelson, whose artwork forms a companion show at the museum this summer; and nationally acclaimed artist Jerry Pinkney, well known at the museum over many years, and his son Brian and daugther-in-law Andrea Davis Pinkney.

They look to the future in an exhibit that moves across an expanse of time. And Phillips-Pendleton looks back to the 200 years and more of contact between European, African and Native peoples on this continent before the nation formed, as she sets out printed images in newspapers and magazines, some realistic and many deliberately distorted, and their relationships with social and political currents of the time.

“We talked a lot about fact and truth,” she said, “and that’s why we thought this was really important, because this is not a point of view. These were illustrations that were printed on these days, for these companies, for these reasons.

“We’re not curating fine art pieces and ordering them a certain way because this is the museum’s story. This is an American story. It’s everybody’s story. And we wanted as many people to see it as we can.”

Phillips-Pendleton opens her exploration into a widening web of narratives as artists of color tell their own stories in print, in Black newspapers and artist studios, in art courses supported by the Works Progress Administration, and through the intense energy of Harlem Renaissance.

As they form their own representations, they reclaim traditions of storytelling and art, and music and performance, political activism and community. And she moves with a new generation of artists into the contemporary world — as their images reach around the planet on new platforms, from The New Yorker to Instagram.

Mining the past, making connections

Thinking back to the seeds of this show, Phillips-Pendleton recalled a love of shared histories of intelligence and courage and community that touch many of the artists she has brought together here.

“I had a cousin in Gloucester, Va., and she passed away at 104, and she knew many of these people,” she said. “Her father was a professor at Tuskegee in the late 1800s, and she had books and photographs of people who came to her home. It probably came from that — it probably was unearthed by loving to go through old photos and hear old stories.”

Her cousin knew a richly intellectual community of Harlem Renaissance artists, like the internationally recognized sculptor Augusta Savage and the friends who gathered in her studio. And she would have known Tuskegee University when the Tuskegee Airmen — Black fighter and bomber pilots in World War II, when the military was segregated — trained there.

This show also has roots more recently in her own artwork, Phillips-Pendleton said, and in talking with artists.

“I’m a working illustrator and an artist myself,” she said, “so I have a lot of friends who are illustrators and have been illustrators for 40 years.”

In casual conversations, they shared experiences in jobs they were working on and compared different fields, like editorial and children’s books, within the industry of illustration. And their experiences revealed patterns of thought and embedded biases.

She recalled discussions of “their experiences with different art directors, and how they were treated by the staff, just dropping off work, the admins thinking they were the delivery person, or having them go through special tests to see if they could actually draw people.

“And I’m thinking, ‘Where did this start? Where did the images start? Who drew Black people and who drew white people? How did this come to be?’”

Just after one of those phone calls, she said, she opened an email from the Illustration Research Organization and found a call for papers. So she turned those questions into a proposal and began researching the history of images in this country.

Illustration and the Americas

Phillips-Pendleton said she began in 1590 with some of the earliest printed images she could trace, as European colonists drew Native people and took the images back to Europe. They showed those drawings, and they bound books, and they came back to the Americas — and a cycle gained momentum.

The artists, mostly white and mostly men, were creating images for popular media: Printing presses were making it possible to distribute pictures and stories to hundreds of thousands of people.

She followed one image to another in her research, finding the artists and printers and editors who created them. She was tracing a web of illustrators and how they saw the world.

And she was uncovering the narratives, and often the biases, they were incorporating into the work they made — some of them obvious in their caricatures and exaggerations, and some more subtle.

“What newspapers did they work for, what the editors’ positions were … what was the political climate like? The images always responded to what was going on in the country, and to this day that’s still happening,” she said. “We never get off of that merry-go-round. … Illustration is part of our culture. It’s part of our thoughts, our feelings, for centuries. It immerses itself into all kinds of things -- things we read, products, things we use every day.”

Getting at the roots

In digging into the back story, she began with her old hometown.

“I kept going back to Hampton, Va., which is where I’m from,” Phillips-Pendleton said.

In 2019, when The New York Times began publishing The 1619 Project, a major feature about the impact of slavery on American history, she knew that ground intimately. The project’s name derived from the year of the first written record of enslaved Africans sold into a European colony in North America. Phillips-Pendleton had grown up near Jamestown, the destination of that first group of slaves.

“I grew up five minutes from that site,” she said. “My research was Port Comfort, Va.”

Growing up, on her visits there and to other historical sites — Williamsburg, Gettysburg — she said she had never heard any discussion of Black history at any of them.

Here at the museum, those missing narratives emerge as artists of color tell their own stories. In Charles White’s “Wanted Poster Series,” a woman stands on an auction block, holding her young son close against her with her hands on his shoulders. Her eyes are dark, and she carries herself with an in-held strength. A sign above her head reads, “sold.

Tom Feeling has invoked men in chains, diving into the sea in the swirling currents of “The Middle Passage.”

“Of the more than 12 million enslaved people brought from Africa,” says the caption beside his charcoal drawing, “only 10.7 million survived the Atlantic crossing and the dire, inhuman conditions aboard cramped, disease-ridden ships.”

Everyday acts, cultural currents

Phillips-Pendleton opens the show with images made in the 1800s, at a point when printing technology in America was often put to use in reinforcing a society based on slavery. She examines the narratives of the era. In popular culture, commercial companies were manipulating emotion then as they do now, she said, and studying them can expose the fears and needs and cultural tides they were riding.

“If we study advertising and culture and even fashion, people always talk about the trends,” she said. “But the trends also relate to race and politics and propaganda. What was the trend that sold products in the 1800s?”

She considers advertisements of the day, popular books and popular entertainment. Minstrel shows appeared then as a genre of performance based in caricature and racial bias, and the characters they enacted give clear examples of stereotypes that consciously or unconsciously reinforced homophobia -- the older Black man or woman who serves a white central character, the enslaved man supposedly happy with his lot, the free Black man embarrassed or humiliated for comic relief, the teenage rebel the story will subdue.

Although emancipation and Reconstruction changed the context, depictions of people of color in advertising continued to reinforce some of the same stereotypes and biases well into the 20th century.

“They used the images of the mammy, the slave,” Phillips-Pendleton explained. “ ‘Oh, it tastes just like …’ That’s why Aunt Jemima’s so popular.”

Advertisers printed these images for hundreds of thousands of people. Seen in this light, she said, the chef on a box of Cream of Wheat holds layers of cultural messages, far more than a man smiling by the stove.

Rastus, the advertising figure for Cream of Wheat, takes his name from a character in Joel Chandler Harris’ “Song of the South” — an enslaved man, an embodiment of the minstrel stereotype who would walk through a plantation singing “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah.”

The power of seeing those images repeated constantly could become a matter of life or death, Phillips-Pendleton said, and it still can be today. Within the show, she offers examples of illustrations that have turned the tide of elections and led to violence.

“When tensions rose in Reconstruction and people were in polarized places — the North, the South — when people said, ‘We’re not doing this, you can’t make us,’ the images were propaganda,” she explained.

Seeing them, she said, people would lash out: “ ‘We’re going to keep it that way. We’re going to make sure they will never be equal.’

“And it’s still happening,” she said.

In a series of Zoom calls as they prepared the exhibit over the course of 15 months, Phillips-Pendleton said she and Plunkett were struck by how often the show’s themes were reflected in current events.

“It was amazing how similar it all was, and is,” she said. “On any given day, something would happen in the news, and we were saying, ‘This is like the 1800s.’ It was those kinds of revelations we were having on a regular basis.”

The kinds of stereotypes she examines here in minstrel shows still carry forward, she said. They are still embedded in contemporary pop culture and film.

“When you have a saturation of it through generations,” she said, “it takes that much time to undo a lot of it, to bring it to light.”

Joyful images like Loveis Wise’s “Taking Care” (2019) bring the show into the present. Courtesy Norman Rockwell Museum

Artists’ images push back

By the late 1800s, though, artists and writers of color were taking a stand in the space of popular media and speaking back, challenging these narratives and raising their own stories in their own images.

Black-owned newspapers and presses emerged in 1827, with the publication of Freedom’s Journal on the East Coast, and grew with the support of journalists and leaders like Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells and many more. W.E.B. Du Bois published The Crisis, the journal of the NAACP.

Among the artists on these walls, Phillips-Pendleton shows the ties of a growing community. Ernest Crichlow was teaching art classes with the Federal Arts Program in the 1930s and painting WPA murals when he founded the Cinque Gallery with Romare Bearden, who would become one of America’s foremost painters.

Bearden took classes with Augusta Savage through the Harlem Artists Guild, and Crichlow also knew her and met friends in her Harlem studio — a gathering point, the show says, for artists like Charles Alston and Norman Lewis.

Finding works from this era could be challenging — and exciting, Phillips-Pendleton said. At first, in the pandemic, borrowing from other museums proved difficult, so she and Plunkett went questing.

“Because we were doing this in Covid, in lockdown, we couldn’t get many of the pieces we wanted,” she recalled. “Many museums wouldn’t lend to us, because they were understaffed and had decided, ‘We’re closing down our lending right now.’”

But she found people who shared her interest and her love for these artists.

“We met so many people who had work,” she said. “The showcase that’s in the historical gallery, most of that came from Leonard Davis. He has had that work in his apartment in Manhattan, and most of it’s never been outside the walls of his apartment. It was like mining for gold. … People had Charles White pieces just hanging on their walls. … ‘Oh, you want to show this? I have a piece of that. I have a Gary Kelly.’

“I’m glad a lot of these pieces are seeing the light of day, because they should.”

Plunkett found a book dealer in New Jersey with material on his shelves.

“She was on her way out the door, and the bookseller says, ‘Oh, I have this’ — and it’s E. Simms Campbell’s map of Harlem,” his exuberant inside view of nightclubs from 1933.

Redrawing the future

Phillips-Pendleton said she hopes to represent many different aspects of illustration in this show — all kinds of expression, from comics to serious pieces to children’s books, music and history.

“Illustration is so vast,” she said, “and it’s everywhere. People don’t realize that. You see it everywhere — it embeds itself in the culture.”

And so, from journeying through the past, however hard and bloody, she brings the show into the present with people living and touching, dancing, laughing, thinking quietly and with joy. Here are Loveis Wise’s loving images of women caring for plants and braiding each other’s hair, and children inventing games, reading, beating rhythms on the stairs — and exploring new planets.

That expression of playfulness, she said, is important, “because there is a lightness when you’re creating books and images for children, and everybody has a way of communicating and should be able to be expressed and seen.

“We have connections with the past and how important that is presently and for the future, and I don’t think they’re separate things — they’re extensions.”

Rudy Gutierrez’ “John Coltrane” is pulsing in colors of paint, reds and golds and filaments of green, and the music Gutierrez has curated for this show spins around the room.

Simone is singing:

There’s a world waiting for you.

Yours is the quest that’s just begun.