Arts & Culture December 2022/ January 2023

Classic diner, community hub

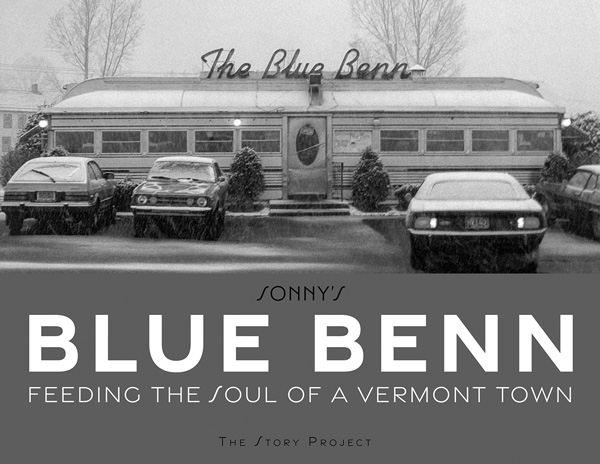

New book celebrates Bennington’s Blue Benn and its longtime owners

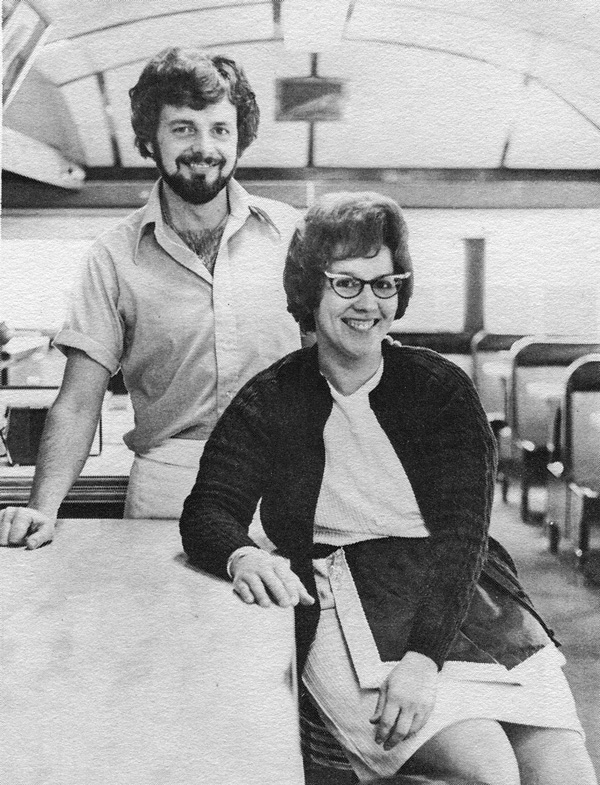

A new book by two area journalists pays tribute to the Blue Benn diner in Bennington and the couple who ran it for nearly five decades, Sonny and Mary Lou Monroe, seen below in 1977. Courtesy photos

By STACEY MORRIS

Contributing writer

BENNINGTON, Vt.

Just up the road from the four corners at the center of downtown Bennington sits a legend.

Make that a legend with a parking lot. Because how else could the faithful townspeople and curious tourists alike pile in for blueberry pancakes, tuna melts and Greek salads?

The Blue Benn diner has been in existence since 1948, when it opened as one of the original “Silk City” diners. But it was during the era from 1973 to 2021 that the Blue Benn became known as more than just a destination for good comfort food. It was during this five-decade span that Franklin “Sonny” Monroe and his wife, Mary Lou, turned the eatery into a place for virtually everyone in the community, as well as those just passing through, the occasional ill-mannered celebrity notwithstanding.

Stepping inside its fabled silver door was the great equalizing experience for a community with a mixture of blue-collar workers, second-home owners, college students and professors, and upscale tourists visiting such attractions as the Williamstown Theatre Festival.

Sonny and Mary Lou set a tone of inclusion and egalitarianism, and the diner’s staff followed suit. The result was that outside-world barriers of socio-economic status and political divisions fell away as diners mingled over coffee and conversation.

When the diner was put up for sale in 2020, it was one of the Blue Benn’s most loyal customers who came up with the idea to immortalize the scope of its community influence in “Sonny’s Blue Benn: Feeding The Soul of a Vermont Town,” a glossy, 174-page coffee table book filled with interviews and nostalgic photographs of the diner’s interior, staff, customers and its beloved owners.

That customer, who wishes to remain anonymous, commissioned local photographer and book designer Peter Crabtree and writer Caitlin Randall of The Story Project to compile photos and interviews for the book, as well as design the final product. The limited edition book retails for $40 and is available at several regional bookstores, but not online.

“This is the first book we’ve done for a general audience in mind,” Crabtree said. “We could have gone the Amazon route, but it would have compromised the quality of book.”

Instead, The Story Project sought the services of Studley Press in Dalton, Mass., a publisher known for producing books for museums and fine arts organizations. The result is a sturdy hardbound volume. Its thick, glossy pages are filled with photographs of the diner’s key characters as well as Blue Benn memorabilia and artwork collected by the Monroe family and longtime fans over the years.

Telling stories in depth

Randall and Crabtree founded The Story Project in 2017 after becoming acquainted over the course of a journalistic collaboration in London. While crafting magazine pieces on Brexit and the Tower of London, the two discovered they worked well together.

Randall was living in London at the time, but two years later, they teamed up to do a story on the Hoosick Falls water contamination crisis for Wilson Quarterly, a current events journal published by the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C.

Both had extensive backgrounds in journalism, Crabtree as a reporter and photographer for the Bennington Banner and Rutland Herald and a freelancer for The New York Times, and Randall as a reporter for Reuters and a writer for publications that have included the Financial Times and The Wall Street Journal.

Now, for The Story Project, they write books on commission for clients ranging from businesses to families seeking an artfully rendered legacy.

“One the one hand, our books tend to go more in-depth on a subject than newspaper journalism,” explained Randall, who now lives in Vermont. “But we’re also writing a tribute, so in that sense, it differs from journalism. There are other companies who do writing for clients, but we offer writing and design.”

Crabtree added that one of the hallmarks of The Story Project is getting each book as tailor-made as possible to the client’s specifications.

For “Sonny’s Blue Benn,” the client requested as many interviews with family members, staff and customers as possible. The result was 37 affectionate recollections of time spent at the Blue Benn.

“This client was really in love with the diner and saw it as a second home during the time they were in college,” Crabtree said. “The client befriended the owners who, in turn, befriended them.”

When the Blue Benn went up for sale in 2020, the client saw it as the perfect time to begin gathering information for a tribute to Sonny and Mary Lou.

Randall said the interview process was somewhat hampered by the arrival of Covid-19 and all of the restrictions that went with the pandemic. But they pressed on, in spite of masking, air purifiers, and supply chain shortages for the proper paper required for the design.

“It took about a year and a half, but we got it done,” she said.

Living the diner life

Their story of the Monroes’ version of the diner opens on Christmas Eve 1973, just after Sonny made the leap of faith to go from Blue Benn employee to owner. He had signed a lease on a whim when the previous owner suddenly bailed out.

A self-trained cook who’d been at the stove since childhood, Sonny had long harbored the dream of having his own restaurant and welcomed the challenge. Mary Lou recalled being “scared to death” at the time, though she also felt there was something inherently right about her husband’s decision.

The interviews throughout the book bear witness to the seamlessness of Sonny and Mary Lou’s teamwork: his passion for feeding others was supported and elevated by her reputation for a no-nonsense but fair managerial style.

Crabtree said the book’s style is modeled after Studs Terkel’s “Working,” in that the diner’s story is told in a series of direct accounts from those who were a part of it.

Randall describes the tribute as a feel-good story with briny doses of realism, such as the frank recollections of the Monroe’s only child, Lisa LaFlamme, about her love-hate relationship with the Blue Benn.

“It was almost like competing with a favorite sibling,” Randall said.

Lisa’s day began at 4 a.m. when Mary Lou roused her daughter for the morning commute to the diner. While her parents prepped for the day’s onslaught, Lisa slept on a cot in the cellar until the 7:30 wake-up call followed by breakfast upstairs.

“Lisa was very open about how she hated getting on the school bus smelling like cigarettes and bacon grease” in the days when smoking at restaurants was the norm, Randall said. “But the anecdote also speaks to the tremendous work ethic of her parents.”

That work ethic was hardly the couple’s only virtue, as Crabtree and Randall tell it. They were just as adamant about keeping menu prices fair and affordable for their customers – and about paying cooks and waitresses a decent wage.

LaFlamme recounted in the book’s introduction how her mother resisted raising prices for more than a decade, even though food costs had risen considerably.

“Lisa also talked about how Sonny and Mary Lou fought for good wages for their workers,” Randall said. “And in turn, there was fierce loyalty from the staff. Some of them worked there 25 or 30 years.”

And while Mary Lou managed the day-to-day operations, Sonny was constantly evolving the menu beyond the staples of hash and eggs and burgers.

“Sonny was an innovative chef who broke new ground by introducing a vegetarian section on menu,” Crabtree said. “He understood his clients and figured out early on he had a captive audience in Bennington College, and they came in swarms for the ‘hippie food.’”

The book has a few extras including a chapter devoted to the phenomenon of the American diner, and a brief chapter at the end recounting celebrity sightings at the Blue Benn over the decades. Customers and wait staff alike recall being elbow-to-elbow with the likes of Marisa Tomei, Ben Affleck, James Gandolfini and Gwyneth Paltrow, who was famously scolded by one of the waitresses when she attempted to cut in front of a crowd with the classic “Don’t you know who I am?” line. As the story goes, the waitress told the actress she indeed knew who she was -- and then remanded Paltrow to the vestibule to stand with the other customers awaiting tables.

End of an era

With Sonny’s passing in 2019, Mary Lou decided to sell the diner the following year. Crabtree said there were a few anxious months after it went on the market.

“A lot of people were worried that it would close entirely or be changed into something they didn’t know anymore,” he said.

But fans of the Blue Benn breathed a sigh of relief when Mary Lou sold it to longtime customer John Getchell, who discovered the diner in 1981 while traveling the country via Greyhound Bus to scope out prospective colleges, including the University of Miami and Colorado College.

A breakfast at the Blue Benn proved to be a game-changer. Getchell recounts in the book how Sonny’s Sir Benn omelet, stuffed with chicken, broccoli, mushrooms and cheddar cheese and drenched in hollandaise sauce, became a big factor in his decision to attend Bennington College.

“John is very candid in describing himself as caretaker of the Blue Benn,” Crabtree said. “About the only change he’s made is the diner now takes credit cards. The chef, Brian Carpenter, was Sonny’s line chef. Sonny trained him; he’s been there forever.”

Randall said that in her interviews with the diner’s customers and staff, she was struck by how the Blue Benn functioned as “a community hangout that enabled people to be put aside any differences and be together as a town.

“It reminds me of [sociologist] Ray Oldenburg’s ‘third place’ where a community can gather and just be themselves,” she said.

Near the end of the book, next to a black and white headshot of a young Sonny Monroe, is Randall’s distillation of the Blue Benn experience: “In the Blue Benn, people looked at each other a little differently, ignored strict social barriers, and let tolerance be their guide. … The diner taught Bennington to sit with neighbors and listen. That was its greatest legacy.”

“Sonny’s Blue Benn: Feeding The Soul of a Vermont Town,” is available at the Bennington Bookshop, Northshire Bookstore in Manchester, the Bennington College bookstore and at Battenkill Books in Cambridge, N.Y.

Visit www.bluebenn.com for more information about the Blue Benn diner. Visit www.thestoryproject.net for more information on The Story Project.