Arts & Culture August 2022

Changing a summer theater’s culture

Williamstown festival works to transform, cast off a toxic legacy

Students head out the back door of the ‘62 Center for Theatre & Dance at Williams College, where the college and Williamstown Theatre Festival have set up a new intensive training program this summer. Photo by Susan Sabino

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

WILLIAMSTOWN, Mass.

Eliana Mabe sits backstage at the Williamstown Theatre Festival with the cast of “Man of God,” talking with the director and the actors.

Mabe, a student from Rhodes College in Tennessee, said she has found it powerful to meet the show’s entirely Asian and Pacific Islander cast and to observe inside the rehearsal space as they created the work together.

“It’s a sacred and vulnerable space,” she said.

She has had two weeks to see the inner workings as the show evolves, and she said she has learned through close contact with the whole ecosystem of the theater festival -- how the director can be flexible and communicate with the cast and the design team, and how the lighting influences the actors in their expression.

She spoke in the midst of a rotation in stage management as she shadowed production manager Tia Harewood-Millington. This summer, Mabe is one of 20 students — 10 from Williams College and 10 from across the country — in the theater festival’s new intensive training program.

She chose to come despite knowing that the festival has gone through turmoil in the past year.

“I’ve been hearing about some of the culture, good and bad,” she said, “and I’ve been hearing it with fresh ears.”

Year of conflict and change

The festival has reinvented its training program in the wake of more than a year of upheaval that has led to a series of other reforms. Mabe is watching behind the scenes as the festival tries to transform itself from the inside.

From the outside, some changes are clearly visible. The festival’s leaders have stripped down its offerings this year, producing just three major plays in July and August instead of the seven that were originally planned and that would have been typical in recent decades.

Interim Artistic Director Jenny Gersten said she and the festival have been focused on the question of how to change a community’s culture, both in the broad climate of the organization and in its practical day-to-day activities.

These shifts have come in response to a movement that gained momentum over the past year and a half.

In February 2021, a collective of festival alumni wrote an open letter to the festival’s leaders and board, raising a systematic set of concerns —concerns the festival has acknowledged as real.

The letter, representing the voices of more than 75 apprentices and interns, designers and staff, focused initially on the festival’s economic structure and its effects on health and safety of the people who have sustained it for decades.

The festival, the alumni wrote, “simply would not function without relying on young, mostly unpaid, untrained laborers to push their bodies through intense physical stress for an unsafe number of hours.”

Citing their own experiences and examples, the alumni said the festival had for years exploited intern labor to maintain its ambitious production schedule. And they pointed to a series of cases in which interns suffered workplace injuries because of a combination of exhaustion, lack of training and lack of protective equipment.

At the same time, the alumni described deeper faults in the culture that grew up around the structure of the interns’ free labor — one that tolerated incidents of sexual harassment, racial bias and abuse of power while providing no meaningful process for reporting these incidents.

To the world outside the festival, these concerns became more visible last summer. In August 2021, a tech crew walked off an outdoor set, protesting unsafe conditions during a thunderstorm.

In September, the Los Angeles Times published an expansive story under the headline, “Inside the battle to change a prestigious theater festival’s ‘broken’ culture.” The story, which the paper said was based on interviews with 25 current and former festival staffers, department heads, apprentices and interns, concluded that the festival functioned not as a professional springboard but as “a development program that exposes artists-in-training to repeated safety hazards and a toxic work culture under the guise of prestige.”

The next month, Mandy Greenfield, the festival’s artistic director, resigned, ending a seven-year tenure. Gersten, who’d led the festival from 2010 to 2014, stepped back in on an interim basis.

Charting a new course

In the months since, Gersten said the festival has made some clear, visible and large-scale changes. It ended both its internship and apprenticeship programs, and it disbanded its scene shop.

In past summers, the festival would have grown from about 12 year-round staff into a corps of 75 apprentices and 100 interns in Williamstown at the height of the summer, with a total of some 600 people involved, including summer staff, directors, playwrights and actors.

This summer, Gersten reckons she has 140 staff and 150 artists in her busiest weeks and about 300 people in all, including actors and students and the “Fridays@3” reading series.

From Mabe’s point of view, the changes have real daily implications. In contrast to past years, the students this summer have their food and housing covered through the training program, and they are paid. They each receive a stipend of $2,500 from the festival.

Mabe spends no more than 46 hours a week involved in the work of the program, in academic study with guest artists, observing festival staff and actors at work and watching plays. The students now have free admission at the Williamstown festival’s shows and an exchange with other Berkshire theaters.

“I’ve been part of other festivals,” Mabe said, “but nothing to this extent.”

In the past, according to the Los Angeles Times coverage, interns and apprentices had to pay as much as $4,000 for the summer to participate in the festival, and according to the open letter, they also paid for their own housing and meals. And they worked long hours — sometimes around the clock.

They wrote of raising cash to cover the festival’s fees by crowd sourcing or taking on debt, believing they would receive professional advancement and contacts in the field. But they said they often wound up isolated and exhausted and sometimes suffered preventable injuries.

In contrast, Mabe said she has found this summer’s training program focused on creative work, academic courses and practical hands-on experience. This summer, the festival has partnered with Williams College and the Williams Theatre Lab and shared its program for study.

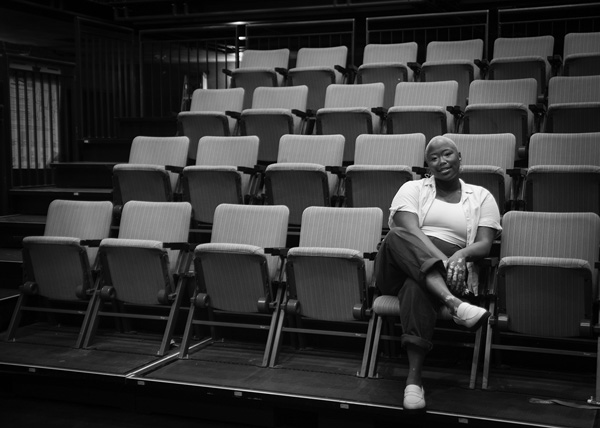

Veshonte Brown, manager of the festival’s new training program, first came to Williamstown as an intern in 2018 and says her experiences convinced her the festival needed to make changes. Susan Sabino photo

Accountability on the ground

Mabe spoke warmly of her mentors -- Veshonte Brown, the manager of the professional training program this summer, and Ann Marie Dorr, the director of Williams College’s Summer Intensive Training Program.

In her experiences so far this summer, she said, the festival has worked for her and her cohort, providing a supportive team.

“In my opinion, especially as a woman of color, it’s important for me to feel safe and to feel — to know -- that what my artistry is doing is making a difference and all my abilities are appreciated,” she said. “I can feel there’s been a lot of change. I’ve felt valued here — that I’m meant to be here. People are excited we’re a part of the program, and we’re meant to learn.”

Brown shared her own commitment to forming and keeping a space where students like Mabe can feel and be seen, heard and free to explore.

She also agreed bluntly, from her past experiences, that the festival needed change.

Originally from Mississippi, Brown first came to the Williamstown festival in 2018 as a graphic design intern. She said that as someone who did not grow up in privilege, and who came here as an intern 2,000 miles from home, she found that first summer extremely lonely, and she has thought often and carefully about how to change that for the young people following her.

Brown said she made professional connections here that first summer, and she has kept them. But she said she would not have come back again without the support of Black Theatre United of New York. The group partnered with the Williamstown festival last summer to create a cohort of 10 theater artists who are Black, Indigenous and people of color, and Brown returned as a member.

Black Theatre United has paused its relationship with the festival and is taking time to assess this year’s changes, Gersten said.

But Brown opted to return this year as a member of the festival’s summer seasonal staff, working to create the kind of experience she had hoped for as an intern.

“You can’t expect people who have been burned to believe you’re changing,” Brown said. “But I like to give organizations a chance — if there’s someone holding them accountable.”

She said the change for the students involved in this year’s festival has been significant.

“As an intern, I didn’t have this,” she said, “and I wish I did.”

Brown said she made the choice to return with careful thought. Some people who knew the festival from the inside called her on that decision.

“’You heard all the stuff,’” she said. “I lived it. And I believe it’s possible to change, or I wouldn’t be here. I hate the phrase ‘change happens slowly.’ That’s from people who think change is theoretical. … I’ve been a Black woman in theater since I was 8. The theoretical is very real to me.”

Change comes from people on the ground, she said. And it may not begin with long-held beliefs or with theater as a whole, but with a chance to build something practical, visible, that has a real effect on the lives of 20 emerging theater artists right now. It’s a chance to stand up for those young people, she said.

“They didn’t sign up to be the answer to all the festival’s problems,” she said. “They’re the proof of the festival’s mission. This program is new. These 20 people are willing to be the first, and they deserve that, to be separate from the festival’s history. WTF doesn’t get to do that, but they do.”

Rebuilding trust

Gersten described some of the work she and the festival’s leaders have undertaken to reckon with its history.

To think with them through questions of equity and accountability, the festival has brought in consultants -- artEquity, a California nonprofit focused on art and activism, equity and diversity in arts and culture, and K+KReset, a New York human resources firm focused on social responsibility and co-founded by nationally respected entrepreneurs who are Black, Indigenous or people of color.

The consultants “have been active with every cast and creative company,” Gersten said, “to meet with every team and with festival staff and the summer intensive students,” and to let them know how they can be in communication and be supported and heard.

“One of the first things they said is, ‘We won’t take this job unless we can hold you accountable,’ ” Gersten said. “Trust takes time, and you have to rebuild it.”

In line with these efforts, the festival created a new full-time position earlier this year: Danielle King joined in March as the festival’s producer of shows and director of organizational culture.

In an interview last month, two weeks into the festival’s summer season, King acknowledged the need to be intentional and honest about the time and rigor that cultural change involves.

“It’s a process, a lifelong practice, as an individual and as an organization,” she said, adding, “I’ve done a lot of listening, a lot of asking questions and observing.”

King said she has met chiefly with people involved in the festival now, rather than in the past. She feels a communal energy here that she wants to encourage and preserve – energy that can only exist in these residencies, when creative people come together to make theater in a flexible place outside the city and the academic world (though they may share resources with both).

“So much can happen in collaboration and creativity and growth when artists earlier in their careers can work alongside established artists,” King said, adding that she sees that concept as something essential to preserve for the festival’s future.

Teaching in a changing world

Brown sees herself doing that work on the ground with the training program -- the work of standing up for the students and creating with them a space of integrity and responsibility and care.

Students in the Williamstown Theatre Festival’s new intensive training program meet in a classroom at the ‘62 Center for Theatre and Dance at Williams College. The program’s 20 students gain hands-on theater experience at the festival, but the much larger internship program of past years is no more. Susan Sabino photo

They have created a community agreement from the beginning, she said. Every person in the space makes a commitment to hold themselves accountable and ways to re-evaluate and respond to concerns.

“The festival as a whole is making it a practice to do that,” Brown said.

She wants to create spaces where the students’ work is not lonely, because they are making something together, and where everyone is treated with respect. And she wants to help them learn the creative discipline of making art.

“I said on the first day, ‘You will never feel unsafe here,’ ” she said.

But they will have space to explore unfamiliar ground, to experiment, she said. And they will work together. In the final weeks of the summer, in August, the students will create a final project, making something that feels wholly theirs.

“These are theater makers,” she said. “We talked about this on the first day.”

In the theater world, Brown said, people increasingly have many more than one field. Over the past decade, there has been a marked shift away from expecting artists to hold only one title or teaching them only one skill.

“They’ll say, ‘I’m an actor, a writer or a stage director,’” Brown said. “You’re a maker. And before all other things, makers are collaborators.”

Mabe said she sees students now involved in many different parts of theater work. They’re multi-hyphenated and excited to take on many roles.

Seeing theater from backstage

Mabe has experience as a director and as a playwright. She said she has been looking for resources beyond her college, because her college has taken them away.

She is entering her senior year at Rhodes, a liberal arts college in Memphis, Tenn. At the end of her sophomore year, the college abruptly shut down its theater department. Though she switched to a major in film, she leads the student-run Theater Guild, and she is teaching and directing children’s theater in her community.

This summer, she said she has enjoyed learning behind the scenes. Through the Williams Theatre Lab, the students have spent their afternoons in workshops and courses with professors and visiting artists.

She had just finished a week of acting with Marc Gomes, an award-winning actor and assistant professor at Ithaca College.

“We wrote and performed monologues,” she said, “and we each got 10 to 15 minutes of individual work, which is rare, to work with a pro there to explain and explore.”

She was looking forward to a week of playwriting and time with Natalie Robin, the program director of theater design and technology at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, with whom she’ll focus on lighting design in musical theater.

Many of her favorite parts of theater, Mabe said, are moments the audience never gets to see: the in-depth conversations between an actor and the character they are thinking their way through, or between the director and the playwright’s work.

“Art is so human,” she said. “So much thought and emotional and physical labor goes into what we do, and it’s even more important now to make these spaces safe and open, because the work we do now can change us.”

Rhodes College is predominantly white, and working there has made her more aware of the power dynamics in theater organizations and the need for changes.

“I’ve been in those spaces, as a minority and as a woman, where I will have to think about whether I feel safe,” Mabe said. “There’s a lot of that inherent in the system of theater. There’s a lot of work that still needs to be done, and I hope all theaters are taking a look at who’s on the staff, … what stories we tell and whose stories they are.”

She recalls vividly in her early college courses realizing that the field she had come into with passion, the art and system she wanted to make a life in, was flawed, through centuries, in ways that have silenced women and people of color.

Mabe said she wants to do the work now to ensure that future generations of students don’t have to make that same discovery at 18 -- so they can come into the field free to stretch themselves, to be curious, to ask life-changing questions, to transform.

Breaking down barriers

As a theater professional with a master’s degree, Brown has developed resources through persistence and time, and she works now to share her knowledge — to bring emerging artists into conversations with established professionals and with each other.

When a student wants to meet a Tony Award-winning director, Brown said, she will reach out to make that happen. And staying up late talking with fellow students on summer nights can matter as much or more, she said. Making contact in the theater world can take many forms.

“People would say, ‘It’s who you know,’ and I hated it,” she said. “I’m from the South. I hadn’t been to New York, and it seemed like a phrase justifying barriers to this art. I think people misuse it. ‘I like directing, and I’m just starting out now and don’t have many credits, but I have a friend who writes.’ … That’s what it means.”

She said she wants to encourage the artists here this summer -- and to stand up for them and see them emerging into the field in the future.

“You can spend your whole life sowing seeds,” Brown said, “and one day you’ll reap them.”

A new generation will take that harvest and sow it again.

“We’re sowing new seeds now,” she said.

Mabe too has seen the power of theater makers creating spaces for themselves. She thinks of the friendship and energy in the original cast of “Hamilton.”

“You can feel that magic -- the love they have for one another and the powerhouse that is Lin-Manuel Miranda, that passion and wanting to leave that mark on history,” she said. “People will find a way to make shows for anyone who will listen. … It’s part of the tenacity and drive to do what we love.”

She looked back to the rapport and confidence she felt in rehearsals of “Man of God.”

“That’s the kind of piece I want to be a part of,” she said, adding that she hopes to be able to return to the Williamstown festival in the future.

“I hope the next time,” she said, “I’m working on a show.”