Arts & Culture November 2021

Tradition reshaped by a changing world

Exhibit traces evolution of Japanese prints in the 20th century

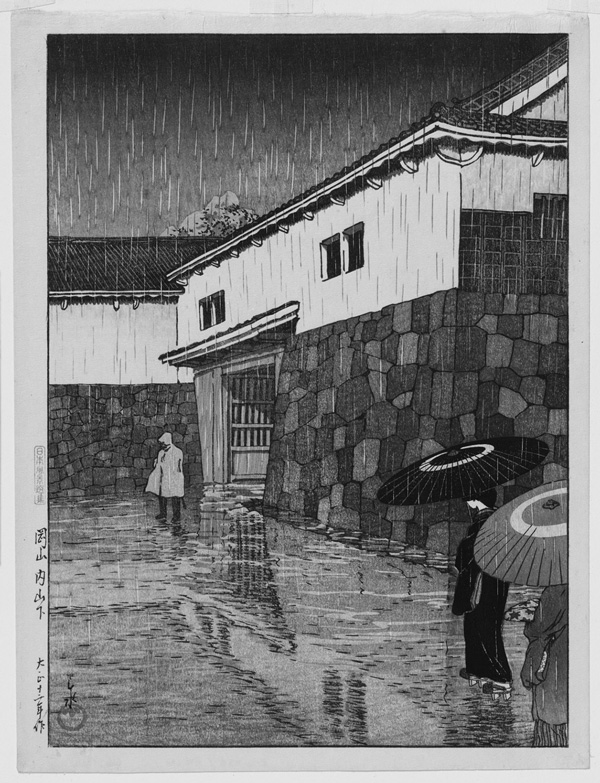

Kawase Hasui’s “Rain in Uchiyamashita, Okayama District” (1923) is among the works included in the exhibit “Competing Currents: 20th Century Japanese Prints,” which opens Nov. 30 at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Mass. Courtesy of Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

WILLIAMSTOWN, Mass.

The ground stretches away to the horizon, and the scuffed earth looks rough and glinting, like a flat sea under a lowering cloud.

In the distance, a low wall stretches in a white streak, with one break and a house out past it. The sky is a deep red ochre, as deep as the leaves that should be falling from the lean, bare trees.

Saito Kiyoshi’s “Autumn in Nanzen-Ji” (1971) is not an inkbrush painting, and it’s not a Kandinsky. But Oliver Ruhl thinks it may be kin to both.

Saito’s work has roots in the centuries-old Japanese tradition of wood block printing, in the contemporary style of Sosaku-hanga. And Ruhl is tracing the way those roots have grown.

This fall he has curated “Competing Currents,” an exhibit that runs from Nov. 30 to Jan. 6 at the Clark Art Institute, tracing two movements in Japanese art in the 20th century as they put forward visions of how woodblock prints could develop as an art form into the future.

Ruhl first got to know them as a graduate student in art history at Williams College, he said by phone from Los Angeles, where he is working toward his doctorate at UCLA.

At Williams, he was working with Anne Leonard, the Manton curator of prints, drawings and photographs at the Clark. Exploring the museum’s collection, Ruhl came to works of Shin-hanga, woodblock prints from the early 1900s.

“I was stunned by them, amazed,” he said. “I hadn’t seen anything like them before.”

Kawase Hasui catches people walking with bright umbrellas under a driving rain and a low overcast sky. Yoshida Hiroshi shows the lights of restaurants shimmering on wet streets at night. These artists came out of a tradition more than 200 years old, and they changed it to show deep and realistic color, city streets and new perspectives.

Their works held his attention, Ruhl said. And he followed them forward, as woodblock prints evolved in and after World War II, and into the 1960s and 1970s. A new movement rose — Sosaku-hanga, creative prints. He finds them experimental, ruggedly visceral and modern. And he is intrigued by the contrast.

Rapid changes, broader horizons

Woodblock prints, Ukiyo-e, became popular in Japan in the 18th and 19th centuries with the growth of a middle class that had the free time and the resources to travel. People wanted beauty and entertainment, a fantasy of geishas and kabuki theater.

For centuries, art had belonged only to the very wealthy, and now wood-block printing meant less expensive images. A merchant could hang a scene on his wall or send a post card from a teahouse.

But in the late 19th and 20th centuries, Ukiyo-e began to seem old-fashioned, Ruhl said. Magazines and photography became popular. It was a time of change, industrialization and political friction.

In 1853, under the threat of U.S. guns, Japan had been forced into new trade agreements with the West. In 1868, the capital moved from the ancient cultural center of Kyoto to the industrial city of Edo — Tokyo — which was and is one of the most populous cities on the planet.

Outside of Japan, Ukiyo-e prints were traveling the world, Ruhl said. They were filling print shops in Paris and influencing Impressionists from Van Gogh to Monet. They were widely popular across Europe and the United States, even as the art form was waning in Japan.

The movement of ideas flowed in both directions, he said. Artists were studying each other’s work, traveling and exhibiting, reading avant-garde periodicals.

Shin-hanga emerged amid the rapid changes of the early 20th century. Shin means new, Ruhl explained. Japan saw many “shin” movements at the turn of the century -- new culture, new politics, new energy.

In 1915, the publisher Shozaburo Watanabe first used this name for the art movement Shin-hanga, new prints. Watanabe wanted to reinvigorate the power of woodblock printing, Ruhl said. Under Watanabe’s eye, a new generation of artists would come to Ukiyo-e with new perspectives.

Amid upheaval, tranquil scenes

Ukiyo-e has a long tradition of detail, fine shades of color and line, and space shown in overlapping planes. One element may appear large and close in the foreground, like a maple leaves from a nearby tree hovering in front of a view across a valley, and smaller elements behind it give a sense of space.

In prints like Hasui’s, Ruhl sees these elements translated. Hasui’s images have a new kind of realism, a point of view Western artists had evolved since the Renaissance, a diagonal sense of space that gives an illusion of three dimensions.

Printmaking can be a slow and careful process, Ruhl said, and it has its own set of restraints. In Shin-hanga, the artist would paint the original scene and hand it to woodworkers who carved the blocks and printers who mixed and layered in the hues. They might keep the artist involved — Hasui could take weeks going over test prints and making changes, like a pianist practicing runs to tone his inflection.

The carvers had to work in minute detail, by hand, and they had little room for error. They could not easily add new elements. They were removing wood to leave only the shape of what they wanted the colored ink to touch. You’re carving around what you want printed,” Ruhl said. “In drawing, you can put more graphite on the page to create a new form. In wood blocks, you’re carving away to create a raised surface.”

That relationship and constraint became one of the central differences between Shin-hanga and its newly evolving cousin. In Sosaku-hanga, or creative prints, the artists make their own blocks, roll their own inks and make their work themselves from start to finish.

Sosaku-hanga artists saw Shin-hanga as conservative, re-creating beautiful sites for a foreign audience, he said.

Ruhl sees Shin-hanga artists showing an element of nationalism, rejecting Western influence. He can see in their ideals a reaction against mechanized, manufactured urban spaces and a look back to a pre-modern Japan.

“You can see that in [Shin-hanga’s] minute, precise reproductions of the natural world,” he said. “Hasui is a master at this.”

Hasui is recalling an almost dreamlike pre-modern Japan, Ruhl said. His images don’t have many power lines or big buildings. He keeps an intentional focus, and his scenes are often outdoors and calm — a stone bridge over a river, or salt marsh and sun on the ocean.

But Hasui’s world was rarely tranquil. He was painting between two World Wars. His “Rain in Uchiyamashita, Okayama District” (1923) survived the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 and the fires that burned through Tokyo — and destroyed the warehouse that held most of his work.

As World War II broke over Japan, Ruhl said, Shin-hanga was ebbing. The war halted many kinds of art as it rearranged artists’ lives.

Into the modern era

In and after the war, Sosaku-hanga emerged more strongly. Ruhl sees in it a wider variety of experimentation and expression. In strong lines, geometric shapes and solid color, these artists were leading a movement toward abstraction. Their work heightens a flattening effect -- much the same effect the planes in Ukiyo-e had brought to Western eyes.

Now contemporary Japanese artists were playing with that effect in new ways, Ruhl said. They brought their own views to Modernism.

They looked to the past and future, sometimes inspired by Japan’s earliest prints, eighth-century Buddhist sutras, and by Buddhist temple architecture and Buddhist clay sculpture images in earth tones. At the same time, Ruhl sees them in conversation with modern artists in the West and with European printmakers, especially the abstract emotion of the German expressionists.

Sosaku-hanga artists often play with a sense of touch, he said. They let the surface of the block show in the print. The textures of the wood curl like folds of cloth in the pattern of a kimono. Or the grain of the wood informs the way a figure is standing or moving, quiet or taut or coiled to spring.

When the artists have the wood in their hands, Ruhl said, cutting the block and mixing the inks, they can have a different feel for what the wood and the colors will do.

“It goes back to the ways they’re working, themselves,” he said. “If I’m a designer and I never touch the wood, you can see how a disconnect may arise. When you’re creating the design and making the carving, you can have an understanding and connection.”

Sosaku-hanga artists had a wider freedom in some ways, he said, not only in making their work, but in sending it into the world. They were not working through a publisher who controlled distribution, so they could exhibit on their own.

In the West, he said, artists were holding their own shows in warehouses and college classrooms when museums refused them. They were opening their own collectives, with actors performing on highway medians and poets printing chapbooks.

In Japan, Sosaku-hanga artists were finding independence both a challenge and a release. More than a few of them worked their way up, Ruhl said.

Saito Kiyoshi, who would become one of the best-known artists in the movement, began as a commercial sign painter. He moved from the country to the city, from Hokkaido in the far north — an island as cold as the Russian steppes — to Tokyo in 1932, and it would take him 20 years to make his name known.

According to the Ronin Gallery, which represents Kiyoshi’s work in the United States, in Tokyo he painted in oils and studied at the Hongo Painting Institute, and he began experimenting with woodblock prints and exhibiting his works with the Japan Print Association in 1936. But he sold his first wood block only late in the war, eight or nine years later.

Kiyoshi began reaching a wider audience among Americans stationed in Japan in the 1950s, Ruhl said, and in 1951 he won international recognition at the inaugural Sao Paulo Biennial. He would go on creating work for a global audience.

In 1967, he designed and printed the first woodcut ever to appear on the cover of Time magazine, a portrait of Japanese Prime Minister Eisaku Sato. He shows the Prime Minister in profile, in shadow with a strong light shining on his face and wood grain rippling in the dark blue background like ocean currents seen from above.

Sosaku-hanga was earning international attention, Ruhl said, and drawing in artists who had never been part of Japan’s established art world. But women had a still harder time becoming part of it. Ruhl has included at least one woman in this exhibit, Shima Tamami. The Clark has a print of her work, “A Stand of Trees” (1959), in its collection.

Tamami appears as one of very few women who have shown their work in the Sosaku-hanga movement, Ruhl said. She graduated from Tokyo Women’s University of Arts (Women’s College of Fine Arts) in 1958 and made more than 60 prints.

In this one, bare trees stand in shades of copper and bronze and gray. A roughened texture shows in the shadows and the surface of the snow. Trails of meltwater or animal tracks trace the slope, and it feels foreshortened, in the way an iPhone photo of a steep hill can look almost flat and level. She gives a sense of distance in the open-sided pavilion just visible through the trees and the grey curve of the mountain on the horizon.