Arts & Culture May 2021

Playful twists on a natural world

Works by French artistic duo Les Lalanne on view at the Clark

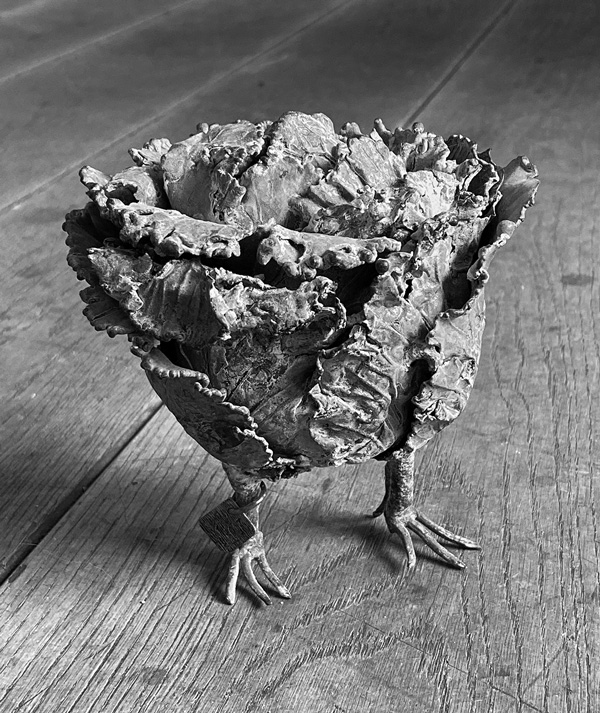

Claude Lalanne’s 2017 sculpture “Choupatte” (Cabbagefeet) is among the works in the new exhibition “Claude & Francois-Xavier Lalanne: Nature Transformed,” which opens May 8 at the Clark Art Institute. Courtesy of Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

WILLIAMSTOWN, Mass.

The old stone buildings in Ury, south of Paris, once held an 18th century dairy farm.

By the late 20th century, the workshops had grown into two artist studios side by side, and the land around them into gardens. Copper and bronze shapes, like the veined rippling cup of a giant cabbage leaf, appeared along the paths and around corners.

The sculptors Claude and Francois-Xavier Lalanne, who lived and worked at the Ury property, were married 40 years (until Francois-Xavier’s death in 2008) and worked together as artists even earlier. Although they seldom collaborated on a sculpture, they always showed their work together under the shared name “Les Lalanne” and became known around the world for their whimsical organic life forms.

This summer, their works will come to the Berkshires for “Nature Transformed,” an exhibition that opens Saturday, May 8, and runs through Oct. 31 at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.

Kathleen Morris, the Clark’s director of collections and exhibitions and curator of decorative arts, traveled to Ury with director Olivier Meslay and curator Esther Bell to talk with Claude Lalanne in the last year of her life. (Claude died in April 2019.)

Morris said she had not known what to expect, and the place kept surprising her.

“Everyone described it as a life-changing experience to me,” she recalled.

She felt a sense of magic that was hard to put into words as she walked the paths and sat in the living room full of the Lalannes’ art and the art of their friends. It was comfortable and welcoming. Claude invited her to take a chair, and she sat next to silvery fish-shaped pillows from Francois-Xavier’s “Sardine Bed.”

Meslay has long admired Les Lalanne, and Morris had come with him to talk with Claude about showing her work and her husband’s, and to ask her blessing.

With this summer’s exhibition, the Clark will become the first American museum to show Les Lalanne’s work in 40 years, though their sculptures have appeared in exhibits and collections from the Centre Pompidou to Windsor Castle.

The Clark had planned to offer this show a year ago, and now, after a pandemic delay, it will open in the Conforti pavilion, with its wall of windows, and outside.

Bronze ginkgo leaves fan into a bench. An enormous carp hovers over the reflecting pool. A rhinoceros can open into a writing desk, and dragonfly wings, lady’s slippers and nautilus shells curl into the bowls of spoons.

Emerging from postwar Paris

Les Lalanne began in Paris in the late 1950s, in Montparnasse, in a community of artists in the Impasse Ronsin, a cul-de-sac of studios that had been a creative center since World War I.

Claude and Francois-Xavier met as young artists in this experimental crowd, in and out of each others’ studios and cheap, barely heated rooms, sharing equipment and ideas.

In their neighborhood, the sculptor Constantin Brancusi shaped the long tapered forms inspired by the flight of birds, and the poet Mina Loy described their lines, “bare as the brow of Osiris.” Isamu Noguchi studied stone sculpture. Later, after World War II, Niki de Saint-Phalle was painting with a rifle, and Jean Tinguely building scrap-metal machines and asymmetrical fountains.

Metal sculptor James Metcalf pooled resources to help Claude set up her metalworking and wrote an essay in the catalog for Les Lalanne’s first show in 1964.

Among these emerging and well-known artists, Claude and Francois-Xavier made a living by creating work for stage productions and shop windows. In the post-war 1950s and ‘60s, in the era of surrealism and abstract expressionism, they were exploring the natural and the real, even when they saw it slant.

They did not follow artistic trends, Morris said. They were not part of any one school of art. They had many friends among the surrealist artists, but they would not have called themselves surrealists.

“They forged their own path,” she said.

That may be, she believes, why they so rarely appear in museums in the United States, because curators question how to describe them. Are they sculptors, designers, decorative artists?

Morris said she sees them as sculptors, but she also believes it doesn’t matter.

The Lalannes said the same. They often spoke in frustration about people who focused on classifications and not on the work itself.

Two artists in a joined name

Morris has created a retrospective to span their careers, from early work to their last years, with an equal number of works from each artist, and at least one collaboration.

They always exhibited under their joined name, she said, and in their shows they never identified who had created which work.

Yet they rarely worked together on one piece, and they had different practices, Morris said.

Francois-Xavier would start with meticulous drawings, like an engineer, and create massive creatures that could look like one thing and transform into another.

At the Clark, a life-sized, 600-pound bronze rhinoceros held a hidden door that folds down into a writing surface. In time, Francois-Xavier would create five rhino sculptures, Morris said. The rhinoceros held a sense of mystery and power for him, a fascination he shared with the surrealist Salvador Dali and the absurdist playwright Eugene Ionesco.

Over the years, Francois-Xavier would create fewer hidden doors and uses but continue to explore a blend of natural and abstract, as in his massive smooth sardines -- or owls with rounded heads and large eyes reminiscent of Brancusi’s human forms.

Claude worked with detail and improvisation and the kind of skill that makes a triple flip look easy. In her studio, she would have metal shapes everywhere, on shelves and tables. She could take up one element from a shelf and combine it with another, Morris said, experimenting, feeling for a moment when it felt right.

She was meticulous, but when she was finished her works would have a sense of randomness, as though they just fell together in a beautiful tangle.

Over time, her works grew in scale. She began with life-sized renderings, Morris explained, because she made them from real leaves or shells or other forms, transmogrified.

She would copper plate them, essentially dissolving copper (in a galvanic bath with an electric current) and coating a leaf or a flower with it. The leaf would be dislimned and leave the metal shape behind.

Over time, Claude began to translate smaller works into larger forms, until her cabbage leaves became almost her own height. She cast them in metal and welded them together, set on absurd chicken feet.

One of the great things about Les Lalanne’s work, Morris said, is that the artists made it by hand themselves. Claude set up her baths and laid her copper plating herself. Even if they eventually sent some of the larger pieces to a foundry to be cast, they put the pieces together themselves and created surfaces and patinas.

At 92, Claude still worked in her studio every day till the end.

And though she and her husband worked in different ways, Morris said she found a similar spirit between them. She feels no sarcasm or alienation in their work, no satisfaction at anyone else’s expense, but an openness and sense of play.

“There’s something so joyful about their work, and so magical at the same time,” she said. “That’s something I love about their work, how much joy is invested in it. It’s a celebration of life, natural and human and animal … It’s hard to look at their work without seeing and feeling your spirits lift.”

And at the end of a pandemic, she thinks people will embrace this sense of humor and hope.