News February-March 2016

In Vt. schools, a merger mandate rankles

Critics say choice, local control at risk in push to cut costs

By C.B. HALL

By C.B. HALL

Contributing writer

ARLINGTON, Vt.

To comply with the requirements of Act 46, Vermont’s new school-district consolidation law, the Arlington district has been discussing such options as a merger with three similar districts -- Poultney, Proctor and West Rutland -- that are about an hour’s drive away. George Bouret photo

When Vermont legislators passed an ambitious school-district consolidation bill last year, supporters said the new law would help small school systems join forces and maintain their viability in the face of declining enrollment.

But here in the hills of southwestern Vermont, the merger guidelines set up by the new law are sowing frustration among local officials in the neighboring towns of Arlington and Sandgate.

The new law, known as Act 46, establishes a “preferred model” in which, by the end of the decade, each of the state’s school districts would have a minimum of 900 students in preschool through grade 12.

The process for school districts to merge is voluntary for now. But by 2018, the state will make plans to combine small districts that haven’t come up with their own consolidation plans. Some critics say the changes demanded by Act 46 will fall hardest on small rural towns.

“Being forced to make a move doesn’t feel good to me,” said Dawn Hoyt, the chairwoman of the Arlington school board, echoing a commonly heard objection to the new law.

Supporters of consolidation, including Democratic Gov. Peter Shumlin, have argued that the state needs to take action to curb rising education costs – and taxes – at a time when the number of students across the state has been steadily shrinking.

But the task of consolidation is a bit like assembling a jigsaw puzzle in which the pieces don’t quite fit together.

The state currently has 280 school districts. Most districts correspond to town boundaries and are grouped together in “supervisory unions” that provide certain services to their member districts. Arlington and Sandgate together make up the Battenkill Valley Supervisory Union, one the smallest such unions in the state.

Arlington, with a population of 2,300, operates an elementary school and a combined middle and high school.

Like 19 other small Vermont towns, Sandgate, population 405, operates no schools. Instead, it operates as a “school choice” district, paying its students’ tuition to the public or private school of their choice. Many of its students attend Arlington’s schools.

The two towns’ educational structures are among at least 13 different organizational formats used by school districts around the state.

Few practical options

Arlington and Sandgate have few realistic options for satisfying the new law’s push for consolidation on their own. The two towns combined have only 412 students – far too few to meet the law’s 900-student minimum for what the law calls an “accelerated merger” option.

Arlington and Sandgate have few realistic options for satisfying the new law’s push for consolidation on their own. The two towns combined have only 412 students – far too few to meet the law’s 900-student minimum for what the law calls an “accelerated merger” option.

For Sandgate, the other choices appear to require a lot of sacrifice for little benefit, to the frustration of local officials.

“I really don’t know what the Legislature was trying to accomplish” with the new law, said Allan Tschorn, a member of the Sandgate school board.

Apart from the accelerated merger, Act 46 offers two other options. The first, “preferred model” requires that a merged district with a single school board have a student population of 900 and operate according to one of four organizational formats. Those formats include “tuitioning” all students to other districts, as Sandgate does now.

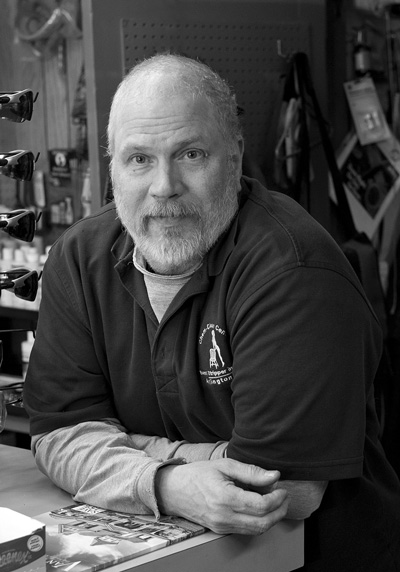

Allan Tschorn is a school board member in Sandgate, which pays to send all its students to public or private schools elsewhere George Bouret photo

But unless other nearby districts decided to shift to an all-tuition system, preserving that format under the preferred model would require Sandgate to merge with most of the 19 other tuition-only districts, which are scattered across the state. That would result in a super-district stretching from Sandgate to Essex County, in the state’s northeastern corner.

The other option for Sandgate is what the law calls an “alternative structure,” a supervisory union not entirely unlike what currently exists. That structure must contain “the smallest number of member school districts practicable, achieved wherever possible by the merger of districts with similar operating and tuitioning patterns,” and must meet the legislation’s overall goals, which include the equalization of educational opportunity and the maximization of “efficiencies through economies of scale and the flexible management, transfer, and sharing of non-financial resources among the member districts.”

Under this scenario, Sandgate could join the neighboring Bennington-Rutland Supervisory Union. Sandgate’s school board is considering merging with Winhall and Stratton, two towns in the Bennington-Rutland union that also pay tuition to send all their schoolchildren elsewhere.

A 2010 state law offers one other alternative, a regional education district. Under what seems the most appropriate variant, that option would require a uniform operating structure and the merger of four districts; it also allows for waivers under certain conditions. So to retain its desired all-tuition format, Sandgate could merge with Winhall, Stratton and Searsburg, to name the three closest all-tuition districts. But all three are on the other side of the Green Mountains, as much as 37 miles away. Although students wouldn’t have to travel that distance, school board members would. It’s a tough sell.

Long-distance partners?

In contrast to Sandgate, the new law’s preferred model of a merged super-district with a uniform structure lies within easier reach for Arlington, whose preschool-to-grade-12 operating format many other Vermont districts share. None of those districts adjoin Arlington, however. That forces the town to look farther afield in the quest to cobble together a preferred-model super-district with 900 students.

So Arlington has been talking with the Poultney, Proctor and West Rutland districts – all more than an hour’s drive. In a merger with those districts, board members from Arlington might face a 100-mile round-trip to attend a board meeting in Proctor, for example. Sharing instructional resources, as the legislation calls for, could mean wearying travel for teachers too.

And critics say all that transportation, accomplished with internal combustion engines, would work against the state’s goal of reducing carbon emissions -- to say nothing of the difficulty of finding teachers, staff and board candidates willing to endure the travel hassles, particularly in winter.

“That’s a problem,” said Tim Williams, an Arlington select board member and former teacher. “That’s a huge detriment to this consolidation.”

Stephanie Brackin, a spokeswoman for the state Agency of Education, responded in an e-mail interview that “more travel and increased carbon emissions is not necessarily inevitable in a merged district.”

“In a merged district,” she explained, “there would be fewer board members, therefore travel overall would be reduced. In some merged districts, parents may actually reduce their drive time, as students may now be able to attend a school closer to home than previously allowed in unmerged systems. ... There is no presumption that teachers would be required to change locations causing them to travel any more than they are now.”

Mix and match

Arlington school officials and their counterparts in North Bennington and Shaftsbury have also been discussing merger into a super-district under the “preferred model.” The rub here is not distance – the districts are contiguous – but the need to agree on a uniform operational structure that fits the requirements of Act 46. Would the voters in all three communities, whose approval would be required, be able to agree on a structure that might upset the status quo in all three of the existing districts?

Finally, like Sandgate, Arlington could wind up joining an alternative structure in the form of the Bennington-Rutland Supervisory Union, said Judy Pullinen, the Battenkill Valley Supervisory Union’s superintendent.

The alternative structure offers a likely choice for many districts that don’t have easy options for creating operationally uniform super-districts. The tendency of districts to stick with the varied structures they already have in place works against the establishment of uniform operating formats that require big changes.

Why, for example, would a community that pays tuition to send its elementary-school children to a privately operated school – to cite North Bennington’s unique structure – want to abandon its chosen arrangement to merge with districts that, like Arlington and Shaftsbury, maintain public elementary school?

The complications increase the temptation to do nothing. But doing nothing places a district at the mercy of the state. In 2018, the Agency of Education will examine how well the voluntary realignments have met the goals of Act 46 -- and will draft plans for districts that have refused to merge voluntarily. It will then finalize a statewide map of districts and send it to the state Board of Education for approval or modification.

Brackin said that doesn’t mean, however, that the state will stuff districts willy-nilly into ill-fitting boxes.

“Consolidation will occur only if it is necessary to achieve the state’s goals and to the extent that it is practicable,” Brackin said, adding that a district will not be merged, for example, “if there is no other nearby district that has the same operating and tuitioning patterns.”

So when local school officials and legislators are asked about the consolidation process under Act 46, no one seems quite sure how it will all play out. Consolidation is a labyrinth through which local decision-makers are proceeding with caution, as one issue after another jumps out at them.

By all accounts, Sandgate and Arlington voters haven’t made up their minds either.

Capping school spending

Apart from its push for administrative consolidation, Act 46 also sets limits on spending increases in each school district. If a district exceeds its cap, the tax on the amount in excess of the cap is taxed twice. With the possible exception of the merger requirement itself, the spending cap has generated more controversy than any other aspect of the law.

Major increases in contractually governed health insurance premiums have been cited as the primary culprit pushing local budgets over the spending-increase brink, but other factors are affecting some individual districts.

“Arlington would be put over the cap just because they’re implementing the pre-K education that the state told them to do,” said state Rep. Cynthia Browning, D-Arlington, who voted against Act 46.

Faced with an outcry from school districts across the state, legislators passed a bill in late January to ease spending caps for the coming fiscal year, and Shumlin was expected to sign it.

Tschorn, the Sandgate school board member, said Act 46 could drive up costs in ways that have received less attention. In an e-mail, he referred to the possible merger with Winhall and Stratton, all-tuition districts that “have voted to pay higher than the state average to independent or private schools.”

In contrast, he said, Sandgate voters have chosen to continue paying the state average tuition. “To form a consolidated district, Sandgate would have to approve higher tuition to independent schools, or the other districts would have to lower their contribution to independent schools,” Tschorn wrote. “Either option could be a sticking point in negotiating a merger.”

Cutting teachers, staff

Williams, the Arlington select board member, said despite the practical hurdles to consolidating rural districts, something needs to be done to rein in school costs – and the spending caps in Act 46 are a good first step.

“We’re terribly overstaffed,” he said of the teacher-to-staff ratio in Arlington, where he taught for 45 years. “Nobody wants to cut teachers. … Problem is, school board members are normally parents. But I don’t think they’re objective. I think the cap was necessary.”

Hoyt, of the Arlington school board, said it’s not so simple.

“It’s fine to say you should cut staff, but where do you start cutting?” she said. “There are more pieces to it than saying, ‘Let’s just cut a teacher or two or three.’”

In a memo she circulated to school boards in October, Browning wrote that staffing accounts for about 80 percent of education costs.

“So the most direct way to control costs is by reducing the growth of compensation, reducing the number of teachers and other staff, or both,” she said.

The three other legislators who represent Arlington and Sandgate, all Democrats, supported Act 46. In an e-mail interview, however, one of those three expressed some remorse: Rep. Steve Berry of Manchester wrote that he’d voted for the bill because “I was told there would be guarantees in place that school choice would continue.”

Preserving school choice

Residents of rural towns like Sandgate see school choice, with the town paying all or most of the tuition cost, as a prized community amenity. The practice lies at the heart of one of the most heated arguments over Act 46.

The law specifies that all school district mergers must preserve the ability of districts like Sandgate “to continue to provide education by paying tuition.” But that provision appears to conflict with another component of Act 46 under which “preferred model” super-districts may not operate their own schools and also provide tuition for the same grade level.

An Agency of Education guidance document states flatly that Act 46 does not authorize a district “to operate a school and concurrently pay general education tuition for a grade or grades operated by the district.” And in September, the state Board of Education also concluded that the law does not allow for a “preferred model” consolidated district “to both operate and pay tuition for the same grade level(s).”

To school-choice advocates, these interpretations threw down the gauntlet. Berry isn’t the only legislator who feels hoodwinked. Fourteen Republican legislators wrote the state Board of Education in October to protest its decision, but the board declined to revisit the matter.

Although the alternative-structure option may afford Arlington and Sandgate a last recourse for continuing with something close to their current structures, some don’t see the point of this exercise.

“Why should Arlington and Sandgate have to beg the state’s permission to keep on doing what they’re doing?” Browning asked. “That’s outrageous.”

Tschorn looks at the law from a school-choice district’s perspective.

“I don’t see how increasing our tuition costs, traveling far to board meetings, or merging with an operating district -- how any of those options accomplish the intentions of Act 46,” he said.

“If we merge with an operating district, we’ve narrowed our scope of educational opportunity” by having to give up school choice,” Tschorn added. “The sentiment on our board and in our community is that we want to preserve our school choice, and we don’t want to increase our operating costs.”

Sorting out the details

Several sources emphasized that community opinion on Act 46 is still a mixed bag as citizens struggle to understand what options the law ultimately will allow or foreclose. For Arlington and Sandgate, figuring all that out poses the immediate task.

“All the school boards are taking all their time on this when they could be taking that time to run their schools,” Browning said.

Some fear that under Act 46, small schools will simply perish, as one-room schools did after their neighborhood districts were consolidated into townwide districts in 1892.

Whether individual schools close will depend on the articles of agreement when districts merge. The merger terms may make it easy to close schools, but those terms are subject to approval by voters in the old districts before a merger can take place.

Whether mergers actually will save money is an open question, Pullinen said.

Even if money is saved at the local level, she explained, “if you have a board that has cut back on services, they may put it back into those services” rather than returning it to the taxpayers.

Hoyt, the Arlington school board chairwoman, said that if savings did materialize, she would prefer to reinvest them in curriculum and technology rather than returning them to taxpayers. She said she felt “90 percent sure” that the other members of her board would agree with her.

Browning said any dollars saved would come at the expense of local control for districts like Arlington and Sandgate.

“I think that for some districts it will save money, and I think that’s great,” she said. “But I question whether the savings in other districts would be enough to compensate for the disruption in the governance system.”

As of late January, legislators by one count had drafted 18 bills to change elements of Act 46. Berry has joined 12 other representatives in sponsoring a bill that would guarantee a district’s right to continue paying school-choice tuition for its students.

Although the spending-cap issue has now been resolved in time for school boards to finalize budgets for consideration at town meetings in March, “the education committees are going to have a lot of other Act 46 problems to look at,” Browning said.