Arts & Culture February-March 2016

Through art, a conversation about race

Exhibit tackles issues raised by Black Lives Matter movement

By JOHN SEVEN

By JOHN SEVEN

Contributing writer

NORTH ADAMS, Mass.

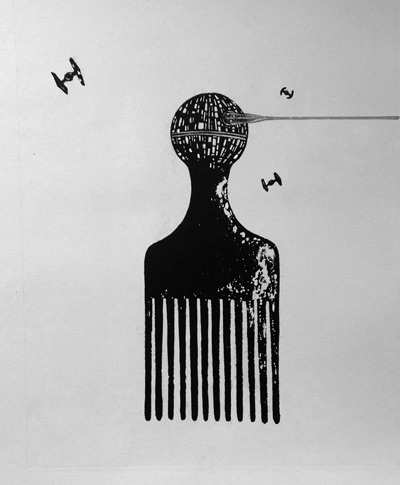

Donte K. Hayes’ “Def Star Pick” was inspired by controversy over the choice of a black actor to play a stormtrooper in the new “Star Wars” movie. Courtesy photo

Black Lives Matter, perhaps the most successful activist movement born of Twitter, is the inspiration for an art exhibition that opens this month at MCLA Gallery 51.

As a movement, Black Lives Matter has been fueled by a series of deaths of black men at the hands of law enforcement. Originating as the hashtag #blacklivesmatter after the shooting of Trayvon Martin in 2013, the movement gained momentum with the deaths of Michael Brown in Missouri, Eric Garner in New York and a continuing list of others.

Activists turned away from their computer screens and took their anger to the streets, helping a much wider swath of the American public to learn about what had been an unheralded reality of many African American communities.

As an art show, Black Lives Matter is the result of the curatorial pairing of two Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts professors. The show features works in multiple mediums by 33 artists, both black and white, from 17 states. It opens Thursday, Feb. 4, with a 5 p.m. reception at Gallery 51, at 51 Main St. in downtown North Adams.

The show’s curators – Melanie Mowinski, an associate professor of visual arts, Frances Jones-Sneed, a professor of history – describe it as an outgrowth of their own conversation about the issues that have driven the Black Lives Matter movement.

Mowinski said she was spurred to action by a Toshi Reagon performance last summer at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art. At one point in the show, Reagon gave what Mowinski describes as a sermon that stuck with her.

“What I took away from it is that if any change is going to happen, I have to do something,” Mowinski said. “I have a printing press; I can do something. What can I do? Who can work with me to do something? And I don’t even know what that something is. I think the something is to have a conversation.”

Mowinski and Jones-Sneed had that conversation together, and Jones-Sneed suggested continuing it in the more public, inclusive format of an art show structured around the ideas of Black Lives Matter. The two women had the notion that their partnership might hint at solutions the problems the movement has spotlighted.

“For both Frances and I, it was important from the beginning that it was a black woman and a white woman working together,” Mowinski said. “If we’re going to make any change in our world, we are going to have to work together as black and white people.”

Answering ‘all lives matter’

From the beginning, Mowinski said, she struggled with the notion that “all lives matter” -- a frequent rebuttal phrase to “black lives matter” that is generally regarded as missing the point of the activism, and which Mowinski said she realizes from her own experience is a marker of privilege.

“That was in many ways my initial response,” she said. “’All lives matter’ is coming from my white privilege. There’s so much that I don’t see because I have this privilege.”

Two artists contributing to the show also touched on this theme in interviews.

Donte K. Hayes of Atlanta said he believes “all lives matter” might be the goal, but it isn’t the reality.

“I hear a lot of times people asking all the time, ‘Why are they saying black lives matter? Everyone should matter. We’re all human beings,’” Hayes said. “Yes, that’s the case, but the point is: There are people in America that are not treated the same. That’s the point.”

Kaytea Petro, a sculptor from San Francisco, pointed out that the phrase “black lives matter” is a specific message about an important life-or-death issue that directly affects the lives of real people. Saying that all lives matter, she said, amounts to “diluting the message.”

“If you look at the statistics, African American men between the ages of 16 to 32 have a really high rate of violent death,” Petro said. “If you can make it to 34 as a black dude and you’re not in jail and you’re not dead, it’s going to be OK. Probably. I think that hashtag needs to stay razor-focused on that issue.”

Petro’s contribution to the show is a collection of clay busts she has fashioned of the unarmed victims of police in 2015. More than 20 figures from the ongoing project will be at Gallery 51; they represent the deaths between Jan. 1 and Feb. 22, 2015.

Petro’s plan is to continue to create these three-dimensional portraits for victims of the rest of the year, to show all of them together, and then, she hopes, to donate the works to the victims’ families.

Petro said she uses the Web site killedbypolice.net to get data for her work. But she was first inspired to focus on the issue after a killing around the corner from her house in 2014. In that case, police fired 59 shots at a 28-year-old man, Alex Nieto, who had pointed a Taser stun gun at them. In an earlier case in the San Francisco Bay area that also inspired Petro, a transit police officer shot and killed an unarmed black man, Oscar Grant, who was lying face down and handcuffed.

“It was happening everywhere,” Petro said. “Being a data nerd, I started to research the unarmed people who had been killed by police, looking into each of these people’s faces, researching the situation surrounding their deaths.”

Petro’s husband is African-American, and she said the shootings have led to multiple conversations between them, highlighting many of the concerns brought to the forefront by Black Lives Matter activists.

“I was talking to him about this stuff -- perceptions of safety, where he feels safe walking around on the streets, and where he doesn’t feel safe,” Petro said. “Me being a white woman, I have very different ideas of what’s safe and what’s not safe, and for very different reasons. I don’t feel particularly safe walking by myself maybe in an unfamiliar part of town that’s not very well lit. That doesn’t bother him, whereas being somewhere that’s very white with a lot of police on the streets makes him feel extremely uncomfortable, but it doesn’t particularly bother me.”

Humor and science fiction

Hayes, who is black, has some of the same concerns as Petro’s husband. One day in Atlanta, he said he was driving his wife’s BMW through an affluent neighborhood when a white man came out to stop his car.

“I didn’t even know this person, and he had a gun,” Hayes said. “He said that he was a cop, but he didn’t have his uniform on at the time, and he didn’t believe that this car was mine. I said no, it’s my wife’s, and I had to prove it.”

Hayes’ art addresses racial disparity, but despite the anger the issue inspires, Hayes chooses to deliver his message with humor and wonder. He incorporates images from science fiction for humorous effect as he examines the black experience in America, such as with his image “Brother From Another Mothership,” which taps. E.T. to express the idea of African Americans as feeling like aliens in their own home.

Another piece, “Def Star Pick,” contrasts an African-American icon and a science-fiction one -- Afro picks and the Death Star – and was inspired by the backlash over having the black actor John Boyega play a stormtrooper character in the new “Star Wars” movie.

“When you see an Afro pick, some of them have a peace sign on them and some of them have a black fist on them,” Hayes said. “Wouldn’t that be interesting to put the Death Star on one? The black fist is a symbol of defiance that says, yes, America, there are black people out here and, yes, we are doing something, and yes, we want you to realize that we are part of this country too. Now we come to 2015. I’m adding the Death Star to it because we are already part of this empire, but we still have to prove ourselves even today.”

Hayes said he would like to see more shows like the one at Gallery 51 all over the place. As a member of the population segment most affected by violence and police misconduct – young black men -- he said he thinks the best way to make things better is to do exactly what Mowinski and Jones-Sneed decided: to have a conversation.

“I’ve realized the best way to stop racism and stop injustice is by actually be able to have a forum that is open to dialogue, open to talking,” he said. “You can listen to my experiences, and I can listen to what you have to say about your experiences, without you feeling like I’m judging you or saying that whatever you understood was wrong. My work is a place for someone who might not even think they have the same ideas.”