Arts & Culture Dec 2016/Jan 2017

Rediscovering the ‘Sage of Saratoga’

Events celebrate life, work of writer Frank Sullivan

By THOMAS DIMOPOULOS

By THOMAS DIMOPOULOS

Contributing writer

SARATOGA SPRINGS, N.Y.

Frank Sullivan, who became best known for his articles and Christmas poems in The New Yorker, lived most of his life in Saratoga Springs.

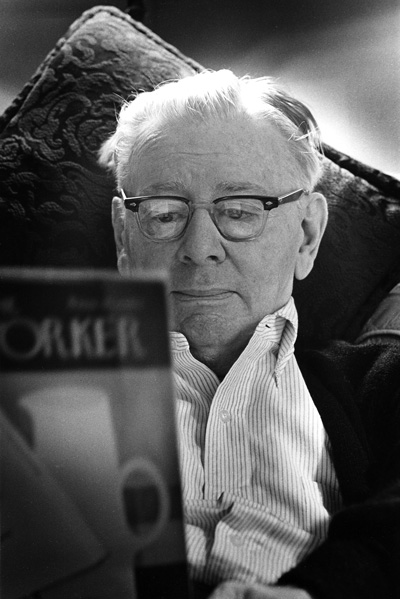

Forty years after his death, Frank Sullivan’s career as a writer is being rediscovered and celebrated in his hometown. Photo courtesy Saratoga Room at Saratoga Springs Public Library

Sullivan’s house on Lincoln Avenue was recently designated a national literary landmark, and a series of local events are planned in 2017 to recognize his achievements.

Sullivan, who was affectionately known as the “Sage of Saratoga,” wrote a dozen books and worked as a columnist and contributor to the New York World, The Saturday Evening Post, and Vanity Fair. But the humorist became best known for his annual Christmas poems and articles that appeared in The New Yorker magazine for nearly a half-century. The Christmas poems ran every year from 1932 to 1974.

“We all knew him as an author and read his books,” recalled Michael Fitzgerald, who spent a good amount of his childhood in the 1940s and ‘50s living within a few yards of Sullivan’s home on Lincoln Avenue. “Every year, you went out and bought The New Yorker to read Frank’s Christmas poem -- to see if he wrote anything about someone you knew in the neighborhood.”

Sullivan was born in 1892 and graduated from Saratoga Springs High School in 1910. After completing his studies at Cornell University, he moved to New York City, where he earned his living as a writer.

“He was a great wit and started off a newspaperman like I did,” said William Kennedy, the longtime Albany journalist and author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “Ironweed.” “When he was alive, he was very well known and popular with the readers of The New Yorker.”

Kennedy, who came of age in the generation that immediately followed Sullivan’s, explained that in the literary circles of the 1920s, Sullivan shared membership with a celebrated group of New York City writers and actors known as the Algonquin Round Table. Through this association he kept company with writers such as Robert Benchley and James Thurber, Dorothy Parker, E.B. White, S.J. Perelman, and Ogden Nash.

“Sullivan and Benchley might have had a cutting edge to their humor, but basically it was as non-serious as they could make it,” Kennedy said, adding that he has a particular fondness for Sullivan’s characterizations of a cliché expert named Mr. Arbuthnot.

“He accumulated all the clichés of the world,” Kennedy said. “It was hilarious.”

Ironically, it was Sullivan’s erroneous reporting of hard news that early on launched his career as a humorist. After his “scoop” reporting of the death of a popular New York City society woman, who it turned out had not died, Sullivan’s editor at the World removed the young reporter from the news beat and re-assigned him to write about lighter topics.

“The motto at the World was: Never let Sullivan within a mile of the facts,” Kennedy said, to which Sullivan replied that that suited him fine.

Hometown and holidays

Sullivan grew up in Saratoga Springs and worked as a pump boy carrying water to bookmakers at Saratoga Race Course.

His childhood home, at Lincoln Avenue and High Street, sat on a plot of land that has since become part of the racecourse property. Shortly before his death in 1976, the city recognized the writer by renaming High Street as Frank Sullivan Place.

Although Sullivan had moved to New York City after college, he visited Saratoga Springs often and eventually settled into a home at 135 Lincoln Ave. that he shared with his sister Kate.

At Christmastime, the neighborhood children were summoned to the home, where they’d sit around the holiday tree. Kate served hot chocolate and cookies, and Frank distributed the gifts.

“I was 8 or 9 years old at the time,” Fitzgerald recalled. “One year, I got a baseball bat and glove. The next year, he gave me a toolbox and a book called ‘The Toy Mechanic,’ which I still have.”

Others from his old neighborhood recall Sullivan shopping for toys in New York City and donating Christmas gifts to the children living at the Hawley Home -- a two-story building on the east side of Saratoga Springs that for 60 years served as an orphanage and temporary shelter for children whose families could not care for them.

“He was a sweet man, witty and down to earth,” recalled Sullivan’s godson Jeff Brisbin, a local musician. “As a 13-year-old, when I first started writing songs, Frank would come over to the house and say, ‘Hey, show me the lyrics.’ It would be something silly thing like, ‘Poor Amy Drew, what happened to you?’ and he would give me constructive criticism: ‘What’s this about? What are you trying to say here?’

“He said you should write down whatever comes into your head, whether you’re writing rhythmically or rhymingly, and then you can go back and edit,” Brisbin said. “‘I always edit myself,’ he would say.”

In November, Sullivan’s home at 135 Lincoln Ave. was designated a national literary landmark by United for Libraries, a division of the American Library Association, in partnership with the Empire State Center for the Book. The library group has previously bestowed literary-landmark status upon the homes of Walt Whitman, Edgar Allen Poe and Ernest Hemingway, among others.

A selection of Sullivan’s writings also was recently chosen as the focus for Saratoga Reads, a community reading and discussion group. As members of the group read Sullivan’s works over the next few months, a series of public events celebrating Sullivan are planned through March 2017 at the Saratoga Springs Public Library. These include a 1930s-themed film night, readings of Sullivan’s essays and stories, and programs dedicated to reflections about Sullivan’s life.

“Given the current state of civil discourse, we believe a little levity in the form of Frank Sullivan’s gentle but incisive wit is exactly what’s called for at the moment,” Saratoga Springs Public Library Director Issac Pulver said.

Sullivan, a lifelong bachelor, died in early 1976 at Saratoga Hospital. He was 83. Portions of his estate were donated to the Saratoga Room at the Saratoga Springs Public Library – which houses his books and his typewriter – and to the Saratoga Springs History Museum, where among Sullivan’s typewritten letters and unpublished manuscripts is a note on White House stationery from then-President Gerald Ford, who wished the writer good health after he had fallen ill.

For more information about Frank Sullivan and a schedule of regional events celebrating his work, visit saratogareads.org.