News & Issues August 2016

Back to the garden

Counterculture lives on as Rainbow Gathering visits Vermont

By TRACY FRISCH

By TRACY FRISCH

Contributing writer

MOUNT TABOR, Vt.

More than 10,000 people are estimated to have set up camp last month in the Green Mountain National Forest near Mount Tabor for the national Rainbow Gathering, an experiment in alternative living that traces its roots to the anti-war counterculture of the late 1960s.Tracy Frisch photo

When thousands of people converged on the Green Mountain National Forest last month for the national Rainbow Gathering, they resumed an experiment in alternative living that has played out, a week at a time, nearly every summer for the past 44 years.

Participants say the gatherings, which have their roots in the youthful idealism and anti-war counterculture of the late 1960s, aim to accentuate the best in human nature. In what becomes essentially a weeklong intentional community in the woods, the use of money and electronics is highly discouraged; instead, people relate to each other with generosity and love.

Those who take part consider themselves members of the Rainbow Family. At the gatherings, people often address one another as “sister” and “brother.” Members of this family also organize smaller regional gatherings and gatherings in other countries.

At the height of this year’s national event, held July 1-7, the U.S. Forest Service estimated more than 10,000 people had made their way to a small national forest site at Mount Tabor, just east of the town of Danby on U.S. Route 7.

The experience of being in a different sort of society began as soon as one passed through the entrance gate. No one staffed it, and admission at Rainbow Gatherings is always free to all. Banners conveyed the message “Welcome home,” and some Rainbow family members took pleasure in greeting new arrivals with that same evocative phrase. Hugs were freely exchanged, and one would overhear people parting with the words, “Lovin’ you,” sometimes to apparently new acquaintances.

The Rainbow Gathering hadn’t been held in the Northeast for about five years. Each year, members of the Rainbow family scout out locations for the next summer’s event. Gatherings are customarily held in a national forest somewhere in the 48 contiguous states, moving to a different region of the country each year.

On Friday, July 1, the first day of the gathering, the line of vehicles parked alongside the road leading past the gate stretched for more than a mile in each direction. By late morning, attendance already hovered around 4,000, according to a forest ranger on site.

Although the Northeast was well represented, the license plates of the cars showed people had streamed in from every part of the mainland -- the Deep South, the West Coast, the heartland from Minnesota to Texas, the mountain states, the desert Southwest and the Mid-Atlantic.

With motorized vehicles prohibited beyond a certain point, attendees had to make their way into the gathering on foot. Most were loaded down with everything they’d need for as long as they were staying – tents, sleeping bags, clothes, tarps, and often drinking water, food and musical instruments. Massive backpacks were common, but people also trundled their gear on all sorts of contraptions: wheeled suitcases, children’s wagons, wooden carts on bicycle tires, folding shopping carts and wheelbarrows.

Utopian retreat

In the Rainbow Gathering’s unusual social milieu, many people go only by their first name, or they adopt names with a spiritual dimension.

Rob, a volunteer at this year’s information booth, said he has been attending Rainbow Gatherings for most of the past 25 years.

“People are more open, easier to connect with, more giving,” he said. “Everyone feels wealthy in some way. Food is an obvious example. People come here and cook food and give food to others.”

It’s a good environment for making friends as well.

“At this point, I know people from all over the country,” he said.

He said he enjoys the opportunity to be with others out in nature and without having to think about money.

“It’s rejuvenating for me,” he said. “It helps me feel better about humanity.”

The downside, though, is having to leave such a welcoming, idyllic environment.

“It can be a bit of a culture shock to go back,” he explained.

Rob said working at the information booth didn’t involve any real job description.

“There aren’t any assigned tasks,” he said. “If something needs to get done, generally someone steps up and does it.”

The Rainbow Gathering doesn’t have paid positions of any kind, a board of directors, a tax status, or any of the other trappings of organizational structure. It keeps happening only because people want it to – and because some them take responsibility to sustain it.

A high point for the week was the July Fourth silent meditation for world peace, a regular feature of national Rainbow Gatherings. It started by dawn and took place in the main meadow, this year’s communal gathering area. Those who had taken part previously described a powerful experience of thousands of people sitting together in silence with a higher purpose. The meditation always ends with a communal Om lasting as long as 20 minutes. Then children and parents parade in, singing “Give Peace a Chance,” followed by dancing and a shared celebration.

The main meadow, a fairly flat clearing in the forest, had the vegetation characteristic of an old field -- young maple trees, ferns, goldenrod and brambles in flower. Footpaths meandered through the meadow to various kitchens and other festival destinations.

At 7 p.m. every night, people gathered for Dinner Circle in the main meadow. A “magic hat” passed at the circle collected donations for the kitchens that produced the dinner.

Special activities were offered every day. A central clearinghouse took the form of a homemade kiosk next to the information booth. It held a message board, ride board, a place for announcements and a schedule of activities.

One could go to sessions on poetry or yoga, a class on American Sign Language, a workshop on traveling hospice or a funk talent show. Some of these workshops and events were held in tepees identified by color. An outdoor wedding was on the agenda one day.

All ages and styles

The rainbow motif is embodied in many aspects of the gathering, most notably in the diversity of those participating, who encompassed all ages, races and body types. Although a large proportion of them were young, there were also families with babies and young children as well as middle-aged and older people.

Some of the crowd outwardly embraced a counterculture look with lots of jewelry, tattoos or piercings, dreadlocks or long flowing skirts or robes. Many men and women chose unusual styles and bold patterns in their dress, but many others wore ordinary or even drab attire and had conventional hairstyles.

Rainbow Family members have been stereotyped as dropouts and fringe characters, but that picture is misleading. People from all walks of life take part in these gatherings. Some are students, artists or drifters, but others described themselves as gainfully employed people who were taking vacation time to let loose.

Contrary to another stereotype, participants aren’t necessarily followers of New Age or Eastern religions. The Jesus kitchen, run by Christians, is a regular fixture at Rainbow Gatherings. Near the gate at Mount Tabor, several men wearing yarmulkes and conservative dress caught up with a friend whose uncut side locks and black coat on a hot day suggested a connection with Hassidism, an especially pious sect of Orthodox Judaism.

Joe, a heavyset man in a plain T-shirt, identified himself as a Mormon and said a close relative was also there. He had traveled to the gathering, his fourth, by train from Williston, N.D., a town at the center of the shale oil boom.

He said he had migrated to North Dakota after his life in Austin, Texas, fell apart. Within two days of his arrival in Williston, he landed a job managing a gas station. That first summer, he shared living quarters in a semitrailer truck with the buddy who had suggested the move.

Now he’s more settled in North Dakota, though dissatisfied with his situation. He tried meditating, but he found prayer came more naturally. He was at the Rainbow Gathering looking for some inspiration for the next phase in his life and a chance to think.

Generosity and community

At Rainbow Gatherings, people take pleasure in freely offering all sorts of things to strangers. On the main path, a woman with a cranky toddler spooned leftovers into the bowls and cups of passersby. A man wandered by with a 5-pound bag of dark chocolate pastilles, shaking a few into the hands of those who accepted.

One of the kitchens was giving away cups of freshly brewed coffee. Earlier there had been honeydew melon to share. An enthusiastic pet owner thrust his new puppy into the arms of anyone who wanted to pet the affectionate ball of fur.

A young man handed out packages of colored sugar water, and another invited people to choose one of the pretty little rocks he had mined in New Hampshire.

Generosity becomes contagious in such an environment. A singer-songwriter named Leah Shoshanah was playing acoustic guitar and singing when several people sat down to listen. One of the listeners held back tears, deeply moved, as she thanked the performer for the song. Shoshanah reciprocated by admiring the woman’s ear ornaments, and then the other woman, who was clad in a many-colored crocheted body suit and hooded knitted robe, took them off her ears and offered them to the singer. She had made all three items.

Shoshanah accepted the gift, carefully fitting them on her own ears. Then she lifted her pendant over her head and presented it to her new friend. They embraced several times.

Communal cooking, usually at named kitchens that pop up at every annual gathering, is encouraged in the spirit of the Rainbow. The kitchens, each with its own character, provide a large part of the food eaten over the course of the gathering.

Handwritten wish lists appear at each kitchen or the path leading to them. Evidently many of the requests are answered. The kitchens sometimes also solicit monetary donations to supplement the in-kind contributions, and volunteers make treks back to civilization to buy needed supplies.

Often people come to gatherings prepared to donate. Two Chicagoans who lugged impressive loads into the gathering planned to return to their van to fetch two 50-pound sacks of rice they had brought to donate to one of the kitchens. A young man who has been working on organic farms for several years had large plastic bags brimming with vegetables to carry in.

At Shining Light kitchen, a man and woman arrived with knapsacks full of produce, which they laid out on the rustic counter. Their gift of wilted greens and blemished vegetables could have been salvaged from a Dumpster. A cook graciously received it and assured the pair it would be incorporated into the next meal. Then they gave away several juicy papayas for immediate consumption.

A handful of people sat around Shining Light’s campfire, where food was cooking in kegs repurposed as huge pots. All fires had to be constantly tended to prevent wildfires.

Shining Light’s menu for one night’s dinner would be rice, beans, pasta salad, and many dozen devilled eggs. The evening before, the kitchen had prepared and distributed 70 gallons of food.

“We made sure no one was hungry,” said one of the people working with Shining Light, who wouldn’t give his name or permission to be photographed. He did say that his family owns a concrete company and that he works as a carpenter and has a middle-class life.

“I have been with the Rainbow for a long time,” he said. “My favorite thing at the festival is doing food. We try to err on the side of healthy.”

When a heavily tattooed Asian man named Theory arrived to help, another Shining Light volunteer named Lucid set him up to chop butternut squash.

(At the Rainbow Gathering, many people end up with new names. The Chicagoans with the rice nicknamed the writer of this story Sister Pulitzer.)

A low-tech laboratory

Lucid, who grew up in Alaska and still lives part of the time in that state, got involved with Shining Light in 2002, a month after the kitchen got off the ground. He was eagerly anticipating Shining Light’s new project this fall, doing disaster relief and humanitarian aid in Central America.

He said they’d been working out the kinks in their various systems for potable water, cooking, and excluding the rain and sun and were finally ready to make the trip.

Rainbow Gatherings serve as a living laboratory for low-cost, do-it-yourself survival technologies. Those coming to the encampments need safe potable water. (Few people manage to carry in enough water for seven hot summer days.)

Kitchen structures are built on site. Upright supports are pounded into the ground, and then the frames of counters and shelving units are neatly lashed together. Strong volunteers carry in plywood and other materials for countertops.

Provisioning water is more challenging. Gravity-feed piping delivers water from streams and springs far from potential pollution from the gathering. A protocol has been worked out over the years to prevent dysentery and other water-borne illnesses.

At an open-air dishwashing station, a man in camouflage with ribbons in his hair explained that water for cooking, washing and drinking was boiled for at least a half-hour before being stored in plastic barrels. With tiny foot pumps, he controlled the flow of warm wash water and rinse water for cleaning pots and dishes. In a final basin, items were sanitized with chlorine.

For excrement, deep trenches were dug and lime provided so everyone could do their part. Signs encouraged dog owners to collect their pets’ wastes and dispose of them correctly.

As a precondition for using the national forest, everything built for a Rainbow Gathering must be returned to the natural environment or removed from public land. Before each gathering, some people show up weeks ahead of time to develop infrastructure, and afterward a contingent of volunteers make the choice to stay until the cleanup is completed.

“We use chainsaws until the end of June,” said Crystal Water, a tie-dye-clad New Age writer with a white beard from Washington state. “We want the celebration week to be quiet and peaceful, with no generators or petroleum, only hand tools, so there’s a race to get everything done by that point.”

Lovin’ Ovens, a bakery that specializes in bread and rolls, constructed three outdoor ovens of rock and mud for this year’s gathering. The mud came from earth that was high in clay. No lime was added, as that would make the mortar more resistant to destruction at the end of the gathering week.

Each mud oven contained a new steel barrel equipped with two shelves. The ovens were designed to heat by convection. Hot air flowed around the circumference of circular baking chamber. On top, a double-decker stack of bottomless tin cans served as the chimney. Helpers at Lovin’ Ovens were patching holes so the smoke would exit through this smokestack.

For mixing and kneading the dough, a large plywood tabletop had been covered in plastic film and duct-taped down under the corners. A tarp strung above protected the work area from the elements.

Experiment in anarchy

One of the things distinguishing the Rainbow Family from most alternative organizations is its lack of designated leaders – whether elected, appointed or otherwise determined. There is no bureaucracy, and no one has a title.

Lucid said that instead of set roles and people in charge, the gatherings have come to rely on a “merit-based system of cooperation.” From what he has seen, if someone has a history of making good decisions, they end up being trusted.

“It’s pretty apparent who has the attention span to follow through,” he said.

To illustrate why he sees this approach as superior to electing those in charge, he gave an example: “Say you get on an airplane and find out that you’re going to elect the pilot …”

In addition to the lack of designated leaders, no one tracks who will be volunteering. It’s whoever shows up. That level of trust and shared responsibility can be difficult for the outside world to fathom, but for members of the Rainbow family, it’s an article of faith.

“That’s how spirit works,” Crystal Water explained. “It’s gonna turn out beautiful. That’s the magic of the universe.”

Elaborating on the Rainbow social structure, he explained, “There’s no hierarchy. We look at everyone as our divine family.

“The troopers come here – they’re part of our family,” he continued. “We have beautiful conversations. They’re here to experience something different from what they usually encounter. We honor them as we honor each other.

“We feel like we’re making a statement by being true to ourselves. The gathering is a time of coming together. The agenda is just being ourselves.”

Keeper of lore shares story of gathering’s early days

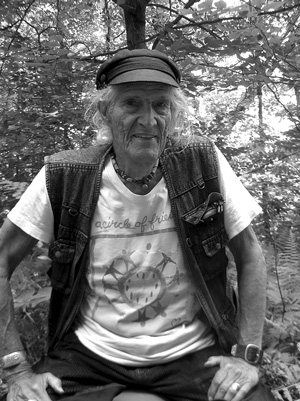

Medicine Story, 87, also known as Manitonquat, has been involved in Rainbow Gatherings since their start in the early 1970s. Tracy Frisch photo

Medicine Story, 87, also known as Manitonquat, has been involved in Rainbow Gatherings since their start in the early 1970s. Tracy Frisch photo

A ritual that the Rainbow family enacts at each of its national gatherings is the telling of its origin story.

This year the ritual was special, with some of “the first ones” and “olders” -- the Rainbow name for elders -- assembling on stage to recount how the gatherings came to be.

On the first day of this year’s festival, one of these elders paused to rest along the main path leading into the gathering.

At 87, Medicine Story is spry and fully present. Manitonquat, as he is also called, is a member of the Wampanoag Nation of Massachusetts. He explained that he is the keeper of lore for the Assonet Band of the Wampanoag, a role he also plays for the Rainbow family. With little prodding, he delved back in its history.

“I went to that little fracas we called Woodstock,” he began.

Two men, Garrick Beck from Rainbow Farm in Oregon and Barry Adam, a “mountain man” from Montana, had a vision of putting together another Woodstock festival, only without money and with nothing for sale. In 1970, Vortex, a weeklong music festival in Portland, Ore., offered a practice run, albeit in a city, for figuring out things like logistics, parking and feeding people.

“With that in their kit, they were going to do a bigger one in Colorado in a ski town,” Medicine Story continued. But the people who lived in that town “were freaking out,” so that gathering never happened, he recalled.

Instead, a man who owned land in Granby, Colo., proposed having it in the National Forest adjacent to his property. Beck sent out a letter inviting everyone. That was the first Rainbow Gathering, in July 1972.

Medicine Story knew Beck as the son of his good friends Julian Beck and Judith Molina. They were the founders of the Living Theatre in New York, an experimental troupe that began in the late 1940s and that he described as “the most radical theater.” They traveled in the same circles because many years ago, Medicine Story also wrote plays and had a theater company called the Off Bowery Theatre.

But Medicine Story left theater behind and in 1967 traveled to San Francisco. Later he reconnected with his roots as a Wampanoag. He then became a columnist and editor with Akwesasne Notes, a prominent Native American newspaper put out by Mohawks in the northern New York.

“I met all these indigenous people from all over the world, and I took that backwards to the beginning,” he said. “That got me started telling stories and doing circles.”

For many years, he and his wife have maintained a busy schedule holding what he calls Circle Way workshops and international family camps all over Europe and in the United States.

A dream of collectivism

Medicine Story said he had a few experiences living in communes in California. None of them functioned well, but rather than reject the notion of communal living, he honed in on why the groups didn’t work and set out to address it.

There was a lack of respect, he said, because “they had lost the primary teaching of the elders.” In traditional peoples, he said he doesn’t see the dichotomy between the individual and the community. If you ask a Navajo who he is, he explained, he’ll give his clan and other group affiliations before he says his own name.

What is key in people coming together is listening, he said.

“Human beings desperately need to be heard, appreciated and valued, and that’s something we can give to each other,” he said.

At the first Rainbow gathering, held in 1972 with 20,000 in attendance, Medicine Story went around to the different campfires telling stories. But at the end, everyone got sick from contaminated water, and a lot of people were disappointed because they had thought it was going to be a rock festival, he said.

The gathering had been envisioned as a one-time affair. Then a group called the Christ Brotherhood in Oregon decided to organize a second gathering. According to Medicine Story, they picked Paradise Lake, in the middle of the Arapaho-Shoshoni reservation in Wyoming, because the state flag had a white buffalo on a blue background.

But they hadn’t gotten permission from the tribes. Beck and Adam stepped in and contacted the elders, who said they didn’t want thousands of hippies descending on their reservation. Beck contacted the sheriff and forest ranger and found a place along Snow Creek in the nearby national forest.

Medicine Story said that it was then that he committed himself to the “Rainbow Gathering trip” forever. He stayed for cleanup and then, in an abandoned school bus they’d found in a ghost town, he and others went on the road for a year to spread the message of the Rainbow family.

After going to Rainbow Gatherings for 17 consecutive years, he now attends irregularly. His last gathering before this year’s was in 2009, for his 80th birthday.

For half the year he lives in Denmark, with his Swedish wife of 32 years, in a commune of 850 adults known as Christiania on the site of a decommissioned military base.

“Since 1971, Christiania has been a free haven, a place for anarchists and rainbows in the city of Copenhagen,” he said.

The other half of the year, he makes his home in a small town in New Hampshire.

For him, one of the highlights occurred in 1978, when the Rainbow Gathering took place in Oregon and a Lakota elder came to check it out. He liked what he saw, and they had a four-hour sacred pipe ceremony.

Ram Dass went that year and then returned the next year when the gathering was in Arizona. Dass, a teacher and the author of the 1971 counterculture classic “Be Here Now,” was a colleague of Timothy Leary at Harvard University in the early 1960s and shared Leary’s interest in exploring the potential therapeutic benefits of hallucinogenic drugs.

Every year on July Fourth they have a silent meditation for world peace. Medicine Story said, “I jumped up on a stump and put my finger to my lips, and Ram Dass hopped up on another stump.”

Wavy Gravy, the comic and peace activist who served as unofficial master of ceremonies at Woodstock, took over the Rainbow Gathering children’s area in 1977. He called it Kiddie City. When he stopped handling this responsibility, Medicine Story said he changed the name to “Kiddie Village with Swami Mommy.”

While he was sharing the gathering’s history, another elder named Feather found a seat beside him, and they reminisced together. Then like any proud grandfather, Medicine Story pulled out several photographs from his wallet and talked about his sons and his grandchildren.