Arts and Culture June 2015

Comic relief for an era’s anxieties

New exhibit reveals the range of cartoonist Roz Chast

By JOHN SEVEN

By JOHN SEVEN

Contributing writer

STOCKBRIDGE, Mass.

As a student in art school, Roz Chast wanted to be a cartoonist but was stuck in a world that looked down on that form and insisted she work on creating fine-art paintings instead.

But with a massive new show that begins this month at the Norman Rockwell Museum, Chast has come a long way since those days.

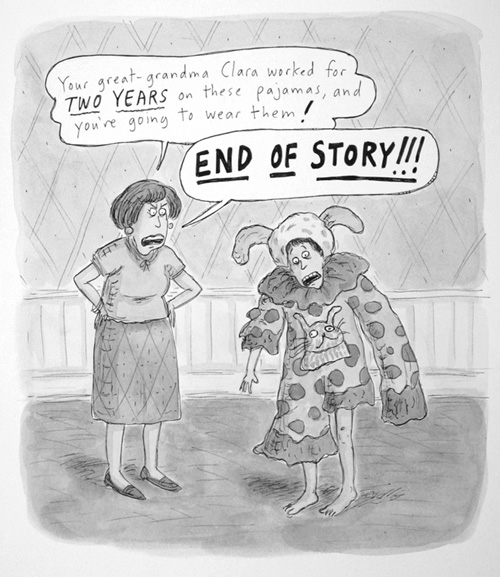

“Roz Chast: Cartoon Memoirs,” which opens June 6 and runs through Oct. 28, will feature 125 images from her recent autobiographical graphic novel, “Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?” The exhibition also includes a section devoted to her work at The New Yorker, as well as sections featuring children’s book illustrations and other magazine work.

Stephanie Plunkett, the museum’s deputy director and curator of the show, explained that the featured work stretches far beyond what most people expect from a cartoonist and illustrator.

“We’ll also have these really amazing hand-painted eggs, which follow the process of traditional Ukrainian egg-making,” Plunkett said. “We’ll also have a couple of her handmade rugs, which are really wonderful. They feature her characters, so they are essentially cartoon rugs.”

The show will include a lot of personal memorabilia and photographs that should resonate with Chast’s fans, as well as a short video interview that visitors will be able to watch to get to know the cartoonist better.

Plunkett said she hopes people will walk away from the show thinking not just of Chast’s visuals but everything that stands behind them.

“The whole idea is to give a broad spectrum of her career and show that she’s constantly looking for creative outlets for her vision,” Plunkett said. “She’s constantly working and trying something new. She’s interested in all different kinds of art forms, and she brings her art to some of these different ways of working.”

Chast’s “Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?” was a nominee for last year’s National Book Award and represents her longest work to date. It follows Chast’s relationship with her parents and the challenges of their aging, revealing one portion of Chast’s personal life in a way that is both honest and somehow exhausting — though not, it seems, in a way that provides any kind of relief for the author.

“The memoir was not therapeutic, I’m sorry to say,” Chast said.

It was, however, a departure for her, something unmistakably about her own life with no area for conjecture, and that’s the only time that has happened, she said. Typically she prefers to mix some parts of her reality into her cartoon world.

“The memoir is the only thing I’ve done that is directly autobiographical,” Chast said. “When I think of funny ideas, they take place in my world, not Charles Saxon’s world or George Booth’s world or Helen Hokinson’s world. But that doesn’t make them exactly autobiographical.”

Inspiration in the underground

Chast fell in love with cartoons as a child, and her attention was particularly captured by the work of her still-favorite cartoonist, Charles Addams.

“His style and his dark, transgressive sense of humor really appeal to me,” Chast said. “There’s something wonderful about seeing not just his cartoons but all cartoons placed inside of very serious articles, as they are in The New Yorker. They’re like a magazine within a magazine. It’s an interesting juxtaposition.”

Chast drew cartoons as a kid and a teenager and eventually discovered underground comics, which kept her working at comics on her own, and to which she can still trace a direct creative line.

“The ones I drew as a teenager were influenced by ZAP Comix, which I discovered when I was around 13,” she said. “I still feel a connection with those early drawings, but I don’t think I’d discovered my particular cartooning world then. I can see glimmers of it, though.”

Art school was the logical route given Chast’s interests and talents, and she ended up at the Rhode Island School of Design. Today, the school is renowned for illustration and offers a comics program. But in the 1970s, the divide between the fine arts and the commercial world was a huge chasm that the fine arts side was perfectly happy to perpetuate.

This caused some creative hardships for Chast, at times blocking her from pursuing her real talents.

“She was studying in art school at a time when any kind of illustration was considered to be a lesser form of art,” Plunkett said. “In fact, she couldn’t really cartoon on a regular basis until after she graduated from art school.”

“Drawing comics and cartoons at RISD when I was there in the ‘70s was definitely not a plus,” Chast recalled. “Once in a while, I showed my cartoons to teachers, but there was no interest. As in: none.”

One thing RISD did give Chast was a feeling that she was not so alone in the world as an artist -- which in some ways was a bit hard on her ego but contributed to her finding herself as a cartoonist.

“It was the first time I had been with super-talented people, people who were way, way more talented than me -- which was depressing at the time, but something that’s good to learn,” she recalled. “I’d always been the ‘class artist.’ Here, everyone was the class artist.”

It was a creative realm that was still mostly male, but Chast didn’t think of herself as a pioneer.

“I didn’t even really think about the ‘being a woman’ part,” she said. “I was still learning how to just be a person.”

Into the mainstream

Chast’s big break came at The New Yorker, where she still works, and where she had no realistic clue that she would end up. Her cartooning style, looser and more casual than what the magazine had generally featured, is considered to have more in common with the underground comics of the time.

“I never thought that I would be part of The New Yorker,” Chast said. “I thought I’d be at The Village Voice, where Jules Feiffer and Stan Mack were.”

Her parents subscribed to The New Yorker, “and of course I knew they used cartoons,” she said.

But when she dropped off some of her cartoons in April 1978, she said, “I really didn’t expect to sell anything.”

She did, and her work was a striking new addition to the magazine’s pages.

“When she started at The New Yorker, she was quite a minority and really had to prove herself in a world of cartoonists that were predominantly male,” said Plunkett.

There was one other woman, Nurit Karlin, who was also selling cartoons to the magazine at the time, and there had been others scattered through its history, but it was far from the norm.

Chast said there was plenty more than her gender to make her feel out of place at The New Yorker, however.

“I think there were so, so many things about me that were weird and possibly disturbing to the old guard,” she said. “Being female was only one in a whole constellation of things: I was a lot younger; my style of drawing was different; my sense of humor was different. Being female was like a cherry on top of the sundae of ‘Who The Hell Is This?’ But eventually, I did make some very, very good friends, people I’m still close with.”

The New Yorker gave Chast more exposure than The Village Voice ever would, especially outside the realm of her logical youthful audience at the time. And that put Chast in the position to build connections that other cartoonists frequently don’t.

Plunkett points to Chast’s unusual ability to resonate with a broad audience as one of the big reasons for her success – and as a reason for featuring her work in a museum show. Chast, she said, is a cartoonist many people recognize and even identify with.

“The show is actually part of a series we have called Distinguished Illustrators,” Plunkett said. “There are so many distinguished illustrators in the world, but most of their names, believe it or not, are not known necessarily, even if people recognize their style. She’s one of the rare names that has become known, and that’s because her art reflects some of the contemporary world anxieties but provides so much comic relief. I think she’s unique in that sense, that people know her and feel like they have a connection with her for that reason.”

But for Chast, none of that is really important as she sits down to do her work. Nor is her place as a trail-blazing woman in the world of cartoonists.

“I really don’t think too much about my ‘importance’ or the female thing,” she said. “There are a few younger female cartoonists whose work I love, and when I get a chance to help them, I try to. But they probably know a lot more than I do.”