News

For a locally grown Passover

‘Vermatzah’ links ancient traditions, contemporary tastes

By STACEY MORRIS

Contributing writer

MIDDLETOWN SPRINGS, Vt.

Micro-bakers Julie Sperling and Doug Freilich have enjoyed a decade of commercial and critical success for their organic, fire-baked Naga Bakehouse breads, but in the past few years they’ve also been developing a seasonal product for Passover.

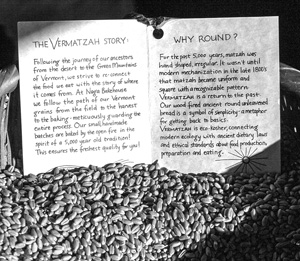

They call it Vermatzah.

The whole-wheat, focaccia and sourdough loaves Sperling and Freilich produce at their mountaintop bakery for most of the year are sold at food co-ops and farmers markets around Vermont, Massachusetts and New York. And unlike many locally baked breads, theirs is made primarily from locally sourced grains.

“The local food movement has exploded over last few years, but one piece missing was grain, and we’ve made a concerted effort to bring it back in,” Sperling explained.

Six years ago, Sperling and Freilich got the idea to use some of their local, organic and sustainable ingredients to make a bread product that is infused with sentimental meaning for them: unleavened bread for the observance of Passover.

“It’s something we’ve been working on for awhile, and we’re getting better and better at it,” Freilich said. “We’re a small farm micro-bakery working with regional growers who provide blends of organic wheat and ancient emmer.”

Because of the quality of their product and the homespun nature of their matzo making, the supply in recent years has barely been able to keep up with demand.

“We have an online presence now,” Sperling explained. “We ship the Vermatzah as far away as Los Angeles.”

So what is it about this particular matzo that incites all those online orders and prompts co-op and health-food-store shoppers to snap it up at a price of about $15 per box?

Freilich says there are two reasons: quality ingredients and a bread-making process guided by the noblest of intentions.

“We work with a handful of growers in Vermont, and we also grow our own grains on a small scale: spring and winter wheats, spelt, emmer, and grains from other parts of the world,” he said. “Ingredients like emmer give the matzo a slight nutty flavor. Some ancient grains aren’t so suitable for bread, but they’re perfect for matzo. Vermatzah represents our baking culture and our heritage.”

And it’s a far cry, both say, from the matzo they were raised on.

“There are a lot of jokes about matzo tasting like cardboard, and the mechanized matzo generally does,” Freilich said. “Vermatzah incorporates a lot of rustic, old-world values. It’s a celebration of flavor, aroma and color that looks and tastes different.”

Season of renewal

So when the farmers markets slow down in the winter months, Sperling and Freilich suspend their commercial bread making for three months, beginning in January, to focus on matzo production.

“We need an income that spans the full year, and this is perfect,” Sperling said. “It’s a condensed effort, and we have the energy and excitement to get it all done before we get back to doing what we do the rest of the year.”

In addition to using locally sourced grains, the couple says their baking method mirrors how matzo was made thousands of years ago.

Rather than offering the square sheets familiar to consumers of industrial-scale matzo makers, Sperling and Freilich, aided by their children -- Tikko, 15, and Ellis, 12 -- shape their round Vermatzah loaves by hand.

“Matzo was made round 5,000 years ago, and we’ve resurrected that tradition as a way of reconnecting to those times as well as reconnecting with the local food movement,” Freilich said. “That’s the platform of our wood-fired bakehouse.”

Having Tikko and Ellis pitch in is also standard practice at the family-run bakehouse.

“When it comes to the production, we couldn’t do it without them,” Sperling said. “We’re not as computer-literate as the kids, and they have created the shipping, invoices and billing system for the business.”

When the matzo is ready for packaging, the unleavened bread is wrapped in parchment paper and then tied in twine in a package that includes a handful of wheat seeds. Also included is a small parchment card telling the story of Passover and how the Jews fled from slavery in Egypt with only minimal possessions plus a few rations of unleavened bread.

“Matzo is a celebration of spring, of new beginnings and the beginning of the new harvest season,” Freilich said. “Because of that, we include seeds so people can plant their own seeds. It’s almost as exciting as the toy in the Cracker Jack box.”

Sperling said Passover has come to mean not only a remembrance of their heritage, but also an awareness of present-day injustices.

“Passover’s about freedom of religion,” she said. “It’s important to retell the story of freedom from the bondage of slavery, but there are a lot of people currently who don’t have freedom, the right to move, and free speech. It’s important to remember and be a socially active and responsible citizen in the world of 2014.”

The final phase of the family’s matzo production involves their Volvo station wagon, which makes deliveries to co-ops and specialty food stores in three states -- as well as to the Poultney post office for cross-country shipping.

“There’s an excitement to the process every year,” Sperling said. “Baking and packaging takes time and care. We’re a small-batch bakery, and Vermatzah has a limited run, and there’s anticipation from our customers. Because every year, we always run out.”

Vermatzah will be available through Passover and is sold locally at Berkshire Co-op Market in Great Barrington, Guido’s Fresh Marketplace in Pittsfield and Great Barrington, Spice ‘n Nice in Bennington, Stone Valley Community Market in Poultney, Rutland Area Food Co-op, Healthy Living Market in Wilton, N.Y., and Honest Weight Food Co-op in Albany. Visit vermatzah.com for more information.