News

A celebration of birds

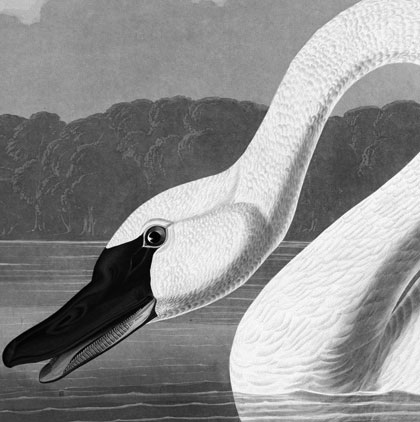

Audubon prints are center of exhibit linking art, science

By EVAN LAWRENCE

Contributing writer

PITTSFIELD, Mass.

Bird lovers, prepare to be delighted.

A new show at the Berkshire Museum, “Taking Flight: Audubon and the World of Birds,” pairs original prints from John James Audubon’s groundbreaking “Birds of America” with a dazzling collection of

mounted birds and a gallery that introduces the wonder of bird life in all its diversity.

Audubon’s multi-volume work, created in the 1820s and ‘30s, is still considered one of the greatest ornithological studies ever compiled, and his large-scale prints are the anchor for an exhibit that

features a variety of other elements.

“The purpose of the exhibit is to bring together art and science,” said Lesley Beck, the museum’s director of communications. Unlike museums that are devoted solely either to the arts, to science,

or to history, the Berkshire Museum’s mission involves joining all three, she explained.

The Berkshire Museum was founded in 1903 by paper magnate Zenas Crane. Stuffed birds and animals were a mainstay of natural history collections of that era, and the museum “has a large collection of

very fine bird specimens,” Beck said.

In 2010, the staff began discussing an exhibit to feature the bird mounts.

“Audubon came up as an aside,” said Maria Mingalone, the museum’s director of interpretation and curator of the exhibit.

Soon after, Mingalone was visiting a college with her daughter and saw prints from “Birds of America” there.

“I thought of combining the two,” she said.

The museum staff was able to secure the loan of 34 Audubon prints in the original double-elephant folio size, about 29 inches by 37 inches. The prints are on loan from the Shelburne Museum in Vermont,

the National Audubon Society, the Arader Galleries in New York City, Williams College’s Chapin Library, and private collectors.

Each print is paired with one or more mounts of that bird, mostly from the Berkshire Museum’s collection. As a visitor enters the gallery where the prints are hung, the array of birds lines up with

the prints behind them: snowy owls, wood ducks, a golden eagle, canvasback ducks, a California quail, common mergansers and many others.

Large scale reveals details

The prints are collaborations between Audubon, who created the original watercolor images, and the engravers and colorists who crafted the prints according to his instructions.

Audubon was obsessive about depicting accurate colors, proportions and poses. He demanded a high degree of accuracy: His birds are not flat masses of color but have individual feathers, individual

scales on their legs and feet, and sometimes individual barbs on each feather. Displaying a real bird alongside its image allows the viewer to see just how well the print captured it.

Audubon’s pictures are remarkable not just for their depiction of birds, but also for the brilliance of their graphic design and the way he suggests the bird’s habitat. Previous bird illustrators almost

always showed birds against a flat white background, so as not to detract from the bird.

Audubon included branches and leaves, fruit and flowers, and sometimes the bird’s prey. In one image, for example, a golden eagle drives its talons deeply into a bloody jackrabbit.

In other images, viewers who look closely may see a whole landscape in the background: a river and waterfall behind the “goosander” (common merganser) pair, or a distant seaport town, complete with

church steeples and ship’s masts, behind the long-billed curlews.

The details are usually invisible in reproductions of the prints, which often are reduced many times from the majestic originals.

“That’s the beauty of the museum,” Mingalone said. “People think they’ve had the experience” by looking at a reproduction.

“But when they see the original, they realize they haven’t.”

In pursuit of the winged

Audubon himself led a life that was almost as dramatic as his subjects. The illegitimate son of a French planter in the West Indies, Audubon grew up in France and did not arrive in America until he

was 18. His early attempts at business were unsuccessful; his real passion was birds.

Traveling from Florida to Texas to Labrador, he shot and then made paintings of all the varieties of birds he could find, using pins and wires to hold the dead birds in lifelike poses.

“Birds of America” was published by subscription. Audubon found patrons, many in Europe, who were willing to front the money for copies of a four-volume, 435-plate work that took 12 years to complete.

The exhibit touches on the human fascination with birds. Artifacts from the museum’s collection show birds painted on a Greek pitcher, birds embroidered on a sumptuous Chinese robe, and birds carved

into Japanese netsuke, tiny sculptures meant to be worn at the waist. Videos in the exhibit show birds in flight.

The exhibit also offers some reminders that the human-bird relationship has not always gone well for birds. Photos and objects document the craze for feather trimmings, especially on hats, that almost

drove some birds to extinction in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. One feather fan incorporates an entire stuffed bluebird.

A case near the end of the exhibit holds three species that are gone forever: the Carolina parakeet, passenger pigeon and heath hen. Ironically, Audubon’s lively print of a flock of Carolina parakeets

is one of his most popular, Beck said.

One gallery in the exhibit is devoted to bird natural history. A stuffed ostrich, the largest bird, stands next to a case containing mounted hummingbirds, the smallest. Another grouping shows the variety

of birds’ bills.

Emperor penguins remind the viewer that birds survive in some of the earth’s harshest climates. Visitors can step into a darkened booth and see if they can locate a squeaking mouse as well as an owl

can. A video shows exotic birds of paradise and the elaborate “love nests” of bowerbirds from New Guinea.

One video not to be missed: the clip of a black bird of paradise shimmying, gyrating and shaking his plumes in hopes of attracting a mate.

Two other current exhibits at the museum complement the themes of “Taking Flight.” “Brian Nash Gill: Beyond the Landscape,” on display until May 28, features sculptures, works on paper, and installations

inspired by the New England landscape. “Morgan Bulkeley: Bird Story,” running until March 4, shows the Berkshire artist’s paintings, which combine recognized bird species, people, cartoon and comic

book figures, and landscapes.

Mingalone, the museum’s director of interpretation, said that although “Taking Flight” wasn’t intended as an exhibit that would travel to other museums, she’d be happy if it did. A previous show of

weapons, “Armed and Dangerous,” is currently at the Memphis Museum of Art. Shows that travel “give us more visibility nationally,” she said.

“The way we approached this exhibit was pretty unique,” Mingalone said. “We’re making connections and appealing to a broad range of people.”

The Berkshire Museum, at 39 South St. in Pittsfield, is open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Saturday and noon to 5 p.m. Sunday. Admission is $13 for adults, $6 for children. Children 3 and under enter free. For more information, call (413) 443-7171 or visit berkshiremuseum.org.

Your Ad could be Here