News

Inner voices, inner strengths

Peer-support approach challenges long-held views of mental illness

By TRACY FRISCH

Contributing writer

GLENS FALLS, N.Y.

Brad Morrow had his first encounter with the mental health system when he was in his late 30s.

In the space of 15 minutes, a psychiatrist he’d never met before told him he had bipolar disorder, gave him some prescriptions and told him to come back in a month.

The diagnosis, so quickly pronounced, became “like a death sentence,” more shattering than the psychic pain for which he was seeking help, Morrow recalled. He’d previously considered himself a “really

creative person,” but the diagnosis changed that. Now he had a label -- and a stigma.

“I felt like my life was a complete fraud, and everything I did and all my accomplishments were based on an illness,” Morrow said.

A major life change precipitated Morrow's initial difficulties. In moving upstate from the New York City suburbs to give his daughter, then in second grade, the kind of small town childhood that meant

so much to him, Morrow left behind his successful career as a chef. He’d owned a restaurant that had absorbed his energy and imagination, and without the identity that came from that, he found himself

lost and depressed.

“I just hid inside myself, and I am a very social being,” he recalled. “It got to the point that I was drooling in my living room.”

The downward spiral slowly ended after five years, when Morrow emerged from his self-imposed isolation to take a job for which a psychiatric diagnosis was a primary qualification. He went to work for

Voices of the Heart, a local mental health organization that’s based on the principle of mutual support, rather than interventions and treatment by people with professional credentials.

The job got Morrow out of the house and involved him in helping others struggling with their own emotional turmoil. In this new environment, he talked with other people who had gone through similar

situations. Hearing their stories and what helped them (and what didn’t), he regained his confidence and started to heal. He has since moved on to another job in the mental-health field.

Planting seeds of change

Voices of the Heart, a nonprofit organization based just outside Glens Falls in Queensbury, is in the vanguard of a growing peer support movement for people in mental or emotional distress. The local

group and others like it, linked through the international Hearing Voices Network, are challenging some longstanding assumptions about mental illness.

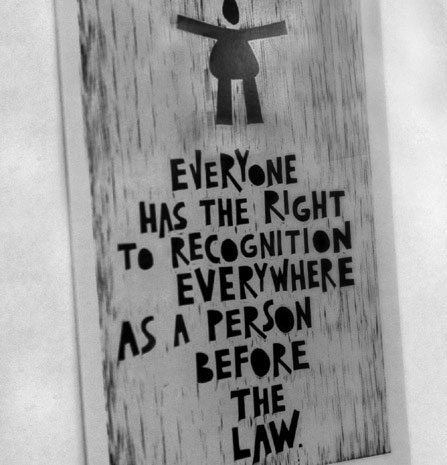

Daniel Hazen, the local group’s executive director, said the concept of peer support grew out of the struggles of psychiatric patients for their human rights.

“Consumers, survivors, ex-patients have been pushing for changes in the traditional mental health model for over 30 years,” Hazen said.

He got involved in the movement about 12 years ago and took his current job in January 2010.

This summer, Voices of the Heart hosted a three-day training session for people from around the state interested in starting Hearing Voices groups in their own areas. The training program, held at

the Queensbury Hotel in Glens Falls, was quickly booked to its capacity of 20 participants; those who signed up were among only 75 people in the United States who’d received this type of training at

that point.

The Hearing Voices movement originated in Europe and has spread as far as South Africa, Malaysia and New Zealand. It is especially strong in England, which has more than 160 chartered groups.

But until recently, the approach had no momentum in the United States, where the biochemical model of mental illness has maintained a strong grip on the psychiatric establishment. Critics say that’s

partly because of the large sums big pharmaceutical companies spend promoting their products to doctors and psychiatrists.

Gail Hornstein, a Mount Holyoke College psychology professor, has been introducing the Hearing Voices approach to an American audience through her book, “Agnes's Jacket,” and an active lecture schedule.

In an interview, she called the “skepticism that people who have been labeled ‘mentally ill’ can get better … one of the great tragedies of psychiatry.”

Buoyed by the positive response to the idea that such peer support groups can provide a path to recovery, Hornstein is spearheading Hearing Voices training sessions in the United States. She led the

Glens Falls training program along with Hazen and Jacqui Dillon, a “voice hearer” at the forefront of the British network.

Nonjudgmental forum

In October, Voices of the Heart started its first weekly Hearing Voices group in Glens Falls.

“It’s a place for people to come who have voices and visions and extreme states,” Hazen said. “The idea is simply for them to share and learn from each other in a mutually supportive way.”

Although working with voices may be considered a taboo subject in conventional mental health settings, Voices of the Heart is respected in the field. Some of its funding comes from the state Office

of Mental Health. This fall, the group held a collaborative training session for 15 mental health providers and 15 voice hearers on working with voices one on one. The workshop was so well received

that another one is in the works for January.

As in other peer support groups, participation is Hearing Voices groups is voluntary. Participants decide for themselves whether the groups are beneficial. Taking part in a group is compatible with

other treatment modalities, including medications.

Hearing Voices support groups differ from group therapy in many ways. First, they are not a vehicle for psychologists, social workers, psychiatrists or other professionals to bring therapy to patients

with a mental health diagnosis. Instead, the groups are non-hierarchical; one or two facilitators, at least one being a voice hearer, convene each group, but they are not leaders in the conventional

sense.

Typically in psychiatry, hearing voices and other unusual perceptions are condemned as signs of pathology. In Hearing Voices groups, however, members explore one another’s experiences with curiosity

and openness. Besides listening, they may offer suggestions and encouragement.

These groups also don't promote social norms or a particular worldview. They provide a space for peer communication that is free of the usual expectations of conformity often found in regular mental

health settings. No one polices whether one is taking one’s meds or demands that one make an effort to contribute to the group or show progress toward some therapeutic goal.

Managing inner voices

Melanie Adkins, a graduate student and home-schooling parent who used to have her own business, traveled to Glens Falls from Watertown, nearly four hours to the northwest, to take the three-day Hearing

Voices training. Her $500 workshop and lodging fee was paid by her area mental health agency. In exchange, she is expected to start a Hearing Voices group in the Watertown area.

Adkins said she has lived her entire life hearing voices, but until five or six years ago she was too afraid to tell anyone about them.

“My husband just thought I was eccentric,” she recalled. “I was 45 years old when I finally came out and said, ‘I hear voices.’”

“I had some very aggressive voices,” she added.

As they had become more intrusive and destructive, even suicidal, she said she couldn’t keep them secret any longer. At the time, she was already seeing a therapist to help her deal with issues from

a horrific childhood.

With a supportive family and care that worked for her, Adkins said she has been blessed.

“I was sent to one of the best hospitals in the country – Sheppard Pratt in Towson, Maryland,” she said. “They used a lot of the same approaches that Hearing Voices uses. … They gave me the tools I

needed to be able to work with my voices, to accept them and be able to manage them.”

Adkins said she still has many different voices, but now the majority help her in positive ways.

“I had to bring them up to date and not live in the past,” she explained.

She keeps journals and has conversations with them. Sometimes she negotiates.

“A couple years ago I told two friends I had Dissociative Identity Disorder,” she said. “They were dumbfounded. They said, ‘How do you hide it?’ I don’t hide it. I was high-functioning enough to pass."

Adkins has had her share of troubles with the psychiatric establishment.

Her first psychiatrist, she said, overmedicated her. She would take her husband with her as an advocate. But when he went overseas, her disagreements with the psychiatrist escalated, and the psychiatrist

threatened to take away her driver’s license.

After one harrowing appointment, she checked herself into a hospital. When her husband returned, they found another psychiatrist.

“I think it's important to find a supportive therapist that works for your whole wellness,” Adkins said. “But you have to search for that.”

Providing a different path

Zach, a Hearing Voices training participant who didn’t want his last name used because he feared the disclosure could jeopardize his new job, said he welcomes “the possibility of providing another

alternative besides going to the doctor, the hospital or a therapist.”

Citing what he called a “glaring lack of choices in the mental health system,” he said one solution is these peer groups because they “are all about empowerment, not pointing a finger.”

Breanna Ayer-Senser, who also attended the training, said she has found

“wellness tools” – creative expression and exercise -- that enable her to control depression and anxiety early. The 23-year-old writes poetry and songs, dances and swims. She also has spiritual guide

visions, which she associates with her Native American and Jewish heritage.

“I don't take medications because of bad experiences,” she said.

She started doing clinical mental health work at 16. Since completing college, she has been working at Voices of the Heart as a peer advocate.

“Voices of the Heart is helping me get the whole core of who I am,” she said.

Associate director Theresa Doherty-Schwartz, who has been on the Voices of the Heart staff since 2007, said she feels society needs to allow and respect diversity in human beings, and not “cast a stone”

at someone “for living in their own reality,” though it may be different from the prevailing one.

Most people don’t question that a janitor deserves the same human rights as a physician, she said.

“So does a person who hears voices that no one else hears or someone who gets depressed or sees visions,” Doherty-Schwartz added.

Instead, “we label them -- that they have a deficit -- and either offer drugs or lock them up,” she said.

But psychiatric drugs aren’t always what people want in their lives, she said.

“We are taking away people's rights to be individuals,” she said.

“When I first joined Voices of the Heart, everyone would introduce themselves to me by saying, ‘Hi, I am bipolar’ or ‘I suffer from depression’ or ‘I am schizophrenic,’ and then follow with their actual

names," she said.

Since then, she said, the culture has shifted away these stigmatizing labels.

A haven at times of crisis

Voices of the Heart got started 13 years ago. The organization serves Warren and Washington counties with multiple programs, all without any out-of-pocket charge. Its trained peer advocates help people

navigate the courts and the mental health and social service systems.

The organization also offer intentional peer support groups weekly in different communities as well as one-on-one peer assistance, and it gives people access to alternative stress reduction modalities

such as acupuncture, reiki, meditation and yoga. It even holds a monthly drumming circle in a park.

In addition, Voices of the Heart runs one of the only nine peer respite houses in the nation. The respite house, an apartment in Hudson Falls staffed with peer advocates, gives people in crisis an

emotionally and physically safe place to get away from a stressful situation while they figure out their options. Often, clients use this haven to avoid landing in a psychiatric ward or jail, staying

for a several days to a couple weeks.

Though it has only two bedrooms, the respite program can potentially save taxpayers hundreds of thousands of dollars annually in Medicaid costs. Hazen testified at a state hearing earlier this year

that his agency’s respite house provides services for about $250 per person per day, compared with more than $1,200 per day if a person were admitted to a hospital mental health ward.

For many people in crisis, the respite house is also a much better option than hospitalization. Going to a hospital can be extremely frightening for someone in need of comfort and reassurance, according

to Hearing Voices training participants who have themselves spent time confined in psychiatric wards.

At a hospital, the staff takes your clothes, gives you a hospital gown, and may put you in a room until they can see you, hours later, because they're so busy, participants said. Sometimes a hospital

will post security guards outside the room.

“I’ve been waiting in that room with someone for eight hours,” said Morrow, who often accompanies people being admitted to hospitals in an effort to lessen their distress.

Shunning drug therapies

Part of the attraction of programs like Voices of the Heart is patients’ distaste for the limitations and side effects of psychiatric drugs.

When Morrow was in treatment, for example, he said his psychiatrist put him on many different medications to find a regimen that would work for him.

“I'd go back every three weeks,” he recalled. “He’d say, ‘How are you doing?’ I would say, ‘Terrible.’”

Psychotropic drugs come with a range of unpleasant and potentially dangerous side effects. These drugs often numb the senses and dull the emotions. They may also cause excessive salivation, dry mouth,

weight gain, organ damage, involuntary movements like shaking, tics and shuffling, suicidal or violent thoughts, as well as various other undesirable neurological, physiological and behavioral changes.

By suppressing extreme emotions, several participants in the Hearing Voices training session said, psychiatric drugs can keep people stuck.

“In my experience, people have to go through these emotions to get through them,” Morrow said. “It’s harder for people who have been in the system for awhile. Nobody has really listened to them or

asked what happened.”

Morrow insists he is not opposed to psychiatry.

“There is not one way that works for everyone,” he explained. “When I look back to what they were doing in medicine and psychiatry a hundred years ago, it was barbaric. I believe a hundred years from

now, they'll be saying the same about our current practices.”

But like Hazen, he suggested that at a time of tight government budgets, more of the mental health establishment will begin to embrace the peer approach because of its cost-effectiveness.

Hazen was honored earlier this year with the Frances Olivero Advocacy Award, given by the New York Association for Psychiatric Rehabilitation Services. Hazen said he was stunned by the unanticipated

recognition, but he calls it as a “telltale sign that we’re on the forefront of changing the public perception about hearing voices and other extreme states.”

Hazen, a voice hearer himself, said the Hearing Voices approach has been an inspiration to him.

“A lot of the things I've experienced through this have saved -- and changed -- my life,” Hazen said. “It’s been a powerful experience.”

Similarly, Morrow recalled how the problems that originally brought him into the mental health system ultimately helped him to grow and change.

“I thought they were just the worst things that could happen to me,” he recalled. “But now I am using my life experience to assist others who are looking for a way out. The negatives have turned into

positives."

Your Ad could be Here