Arts & Culture December 2021- January 2022

For winter, art inspired by snow and ice

Famed snowflake photos offer starting point for Bennington group show

Erik Hoffner’s “Ice Fishing 12” is one of a series of photographs he’s taken of ice-fishing holes that have frozen over. Some of these photos are included in the new group show “Transient Beauty” at the Bennington Museum. Courtesy of Bennington Museum

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

BENNINGTON, Vt.

Ice crystals form like stars: They take shapes too small for human eyes to see, fractal patterns, repeating smaller and smaller until they vanish.

In a new show at the Bennington Museum, these crystals are echoing in translucent glazes, quartz and silver, abstraction and calligraphy.

In this uncertain holiday season, many creative places are turning attention to snow and winter and the night sky, whether in the new “Museum of the Moon” installation at the Berkshire Museum or at Naumkeag’s outdoor “Winterlights” holiday show. The Mount brings fire and music into its winter gardens in “NightWood,” and Hancock Shaker Village offers evening walks around the round stone barn, where cows and sheep are settling in for the night.

At the Bennington Museum, snowflakes are translated into contemporary art in “Transient Beauty,” which runs through Dec. 31.

The show draws its inspiration from a Vermont artist who became known across the world. On a farm about a hundred miles north of here in 1885, Wilson Bentley became the first person to successfully photograph a single snowflake, close enough to see the patterns the ice crystals form. He showed the light crystal structure against a dark background in more detail anyone had seen before.

It wasn’t easy, focusing in closely enough and taking the photo before it melted. The process took Bentley years to develop. He wrote that his mother gave him the tools and the fascination. She had been a teacher, and she had a small microscope that she had used in her classroom before he was born.

“I was absorbed in studying things under this microscope: drops of water, tiny fragments of stone, a feather dropped from a bird’s wing, a delicately veined petal from some flower,” he wrote. “But always, from the very beginning, it was snowflakes that fascinated me most. The farm folks up in this north country dread the winter, but I was supremely happy, from the day of the first snowfall, which usually came in November, until the last one, which sometimes came as late as May.”

Bentley would capture many snowflakes — so many that he is credited with demonstrating that no two of them are the same. In his lifetime, he took more than 5,000 images in gelatin silver prints. He called them photomicrographs. And if every snowflake is really unique, he made images of crystalline forms that no one else will ever see again.

Curator Jamie Franklin acquired one for the Bennington Museum. He said he has known Bentley’s work for years, and it felt like a natural focus for a winter show.

Leslie Parke’s oil painting “Melting Frost” is one of a series of explorations of the frost on her studio window. Courtesy of Bennington Museum

Holiday fund-raiser

Each holiday season, Franklin chooses a work in the collection or from the region and handpicks regional artists in the community whose work connects for him, and the show becomes an auction to benefit the artists and the museum both.

“We take an idea or a theme or an artist and dig deep,” he explained. “And Bentley’s work has so many facets, no pun intended.”

The artists this year have responded in reflections, geometry and early forms of photography.

Leslie Parke brings studies of water on glass, stippled and translucent and abstract.

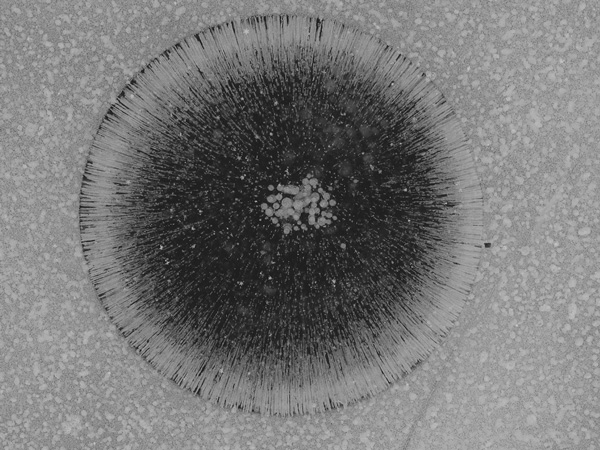

Erik Hoffner’s photographs of intricate patterns in ice transform the holes ice fishers bore in local ponds. Frozen in again, they gleam like an astral body in a night sky, or cells, or eyes.

Light script flows against a shifting ice blue, as Daisy Rockwell draws from Robert Frost, translated into Urdu. And facing her lines, in gold, clear lines of Arabic script read “Bennington Vermont,” surrounded by geometric patterns, rivers and cedar trees.

Ahmad Yassir is an artist and teacher in North Bennington and manager of initiatives, programs and partnerships at the Sage Street Mill. In his work here, the Bennington College alumnus is drawing connections between his hometown in North Bennington and his home country.

They are both landscapes of conifers and mountains and rivers, he said. Lebanon is a green country on the Mediterranean, rising quickly from the sea to the highlands.

“It’s the only Middle Eastern country that is not a desert,” he said. “You can go for a swim, and in half an hour you can be on a mountain and snowboarding.”

He finds connections too between snowflakes and the art of the Middle East — in their symmetry and patterns. Middle Eastern art often calls for minute perfection in form, like the fine control in a line of script or the sculpted geometry of the vaulted ceilings of the Alhambra, or the starred mosaic tilework on the walls and floors, or woven Persian rugs.

Yassir said he wants to recognize the labor in that kind of clear repetition, and the care and time it takes. In the West, scholars have often dismissed Islamic art as “decorative.” He wants to show the skill and beauty in it.

And at the same time, he wants to make it his own. He calls these two works “Local Abrash.” In Arabic, abrash means the unique irregularities that come from making something by hand.

Tradition and innovation

These are not traditional calligraphy, though Yassir has practiced traditional forms for many years. As a teenager he took part in national competitions, he said, and he found he was not winning because he was more intrigued by making his own forms.

As an aspiring artist at home, he grew up sketching, and he found that people around him seemed to hesitate to take art seriously. Because Islamic art is built on such a long tradition, they felt it was too old or too hard, he explained.

Coming to Bennington College and working with professors who encouraged him, he has developed his own art practices, and he wants to encourage this kind of contemporary innovation for his students here and for his contemporaries across the Arab world.

He also wants to revive practices that have centuries of tradition and are fading.

“Glassblowing is a dying practice, and the same for woodworking and everything that is considered an Islamic art,” he said. “They’re dying because they are so traditional.

“I find that similarity between Islamic and Quaker art: We have that idea that we’re not creators, and so we can’t draw portraits, and the solution is to draw paradise or natural elements. My process is trying to figure out how to do Islamic art with the fewest constraints. I want people to question and change their minds, to become more open-minded toward the idea of art making.”

This show has motivated him to come back to calligraphy again, Yassir said, and now he imagines continuing the work in new ways, playing with abstraction, color, language.

New view of a Frost poem

Rockwell said she too has found this show opening her to new approaches. On the wall facing Yassir’s work, her Urdu script fans out against a background washed in deep dusky blue. The words in English would be familiar from Robert Frost’s “Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening” — lines he wrote just up the road in Shaftsbury.

Rockwell said she began by looking for a ghazal, an Arabic form of poetry, about snow. She is a painter in North Bennington and a translator of Hindi and Urdu literature into English. She hoped to translate a poem with images that would speak to Bentley’s work.

She went searching with her friend and co-translator, Aftab Ahmad, a professor in Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies at Columbia University, and they could not find a single verse about snow. They could find only one word for snow or ice, a word usually used to suggest the coldness of a lover.

So they turned to Frost, she said, and she found the reversal illuminating.

When they work together, Rockwell said, she often asks Ahmad what a word means in Urdu. Now he would ask her for nuances in English. He would ask her about a phrase like “without a farmhouse near” and she would try to encompass all a reader in Vermont would feel and understand when they thought about a farmhouse on a winter day in 1922. She would try to explain warmth and shelter, loneliness and changing ways of living.

Ahmad came to understand that a farmhouse meant more than a building, she said, and he chose a word with an inflection of home.

Rockwell said she found it fascinating to take something so familiar and pull it apart — and see it through the lens of a new language. The poem came alive for her again, complex in a way it had not felt in years, as she and Ahmad talked about how to find a word for woods, or for a single flake of snow, and how to understand the relationships between the people and the land.

Whose woods these are I think I know …

Light, water and a lens

Ice can reflect in more than one direction. In “Transient Beauty,” Joanna Gaber has evolved 25 distinct images from a single photograph of light on water.

Gaber calls her process macrophotography, and like Bentley she said she has become absorbed in photographing “the inner and intimate dimensions of flowers, hidden from the naked eye, found only through the lens of the camera.”

But where Bentley recorded microscopic details with precision, Gaber transfigures hers into kaleidoscopic abstractions. Keeping the color and shifting light of the original image, she forms her own fractal patterns and mandalas.

Gaber described her creative process as “first the water, then my eye, then the digital camera and my imagination.”

These images are new, made for this show, and she said she thinks of them as mapping invisible patterns of energy, fluid as subatomic particles, moving between microscopic worlds and galaxies.

As a painter and photographer, Gaber also has followed other callings. She was an assistant professor of philosophy and sociology in her native Poland; more recently she was night librarian at Williams College.

These images feel meditative to her, she said, like a portal, and while these are each about a foot square, she has some large enough to walk into.

“I’m opening something,” she said.

Visions forged in ice

Across from Gaber’s images, stars and cells revolve in Hoffner’s photographs too. He has also been studying ice crystals for years, two decades and more.

Hoffner said he and his wife love to skate outdoors on local ponds. They moved to western Massachusetts from the Southwest, and in their first year, they rented a house on a lake. They had a cold winter and a dry December, and they would put their skates on every day and explore for hours.

And he began to pay attention to the sites used by people who’d go ice fishing on the lake. They would drill into the ice, leaving an open round hole, and then they would leave, and the opening would freeze again overnight. Hoffner saw these places as dark circles in the ice -- ringed with filaments of crystal, like the iris of an eye.

“I would see them the next morning, and it would blow my mind,” he said.

He would come back to them and watch them change over time, as cracks crossed them and rain pitted them and snow blew into the indentations.

Hoffner said he admires Bentley, and he enjoys being part of this gathering responding to a Vermont artist.

“One of the most resilient things about our lives is community,” he said.

Yassir also feels that sense of community from the exhibit.

“I’m not from here, but I’ve been here long enough to be appreciated as a local,” he said. “Any person who comes to a new place has a lot to bring, their uniqueness. … As someone living here, studying, building relationships, the more I see connections. And people are becoming open to it.”

He said he finds the people around him accepting, and he values that warmth. As someone who has studied and taught internationally, Yassir has found a sense of acceptance again here. He often walks around North Bennington, and people will stop and talk with him.

“If there’s anything I miss at home, it’s walking down the street and saying hi to people,” he said.

He remembers the casual friendliness of a neighborhood, knowing the people who live and work around you, and picking up a conversation at the corner store or the coffee shop … or at the local museum, with another artist who has traveled the world and come home.