News & Issues February-March 2018

Spreading solar by the share

Community-sponsored energy project is first for Columbia County

A new 214-kilowatt solar power installation in the town of Clermont, N.Y., was built using a “community solar” concept in which local people could buy a stake in the project in exchange for credits on their home utility bills. Courtesy photo

A new 214-kilowatt solar power installation in the town of Clermont, N.Y., was built using a “community solar” concept in which local people could buy a stake in the project in exchange for credits on their home utility bills. Courtesy photo

By JOHN TOWNES

Contributing writer

CLERMONT, N.Y.

A new concept that could give many more electricity customers a direct stake in solar power has just made its Columbia County debut.

Backers of a new 214-kilowatt “community solar” installation in the town of Clermont celebrated with a ribbon-cutting ceremony in December as their field full of solar panels went online.

The idea of community solar is similar to the concept of community-supported agriculture, in which a farm’s customers pay in advance to buy shares of its produce. In community solar, individual consumers band together as members or owners of a solar installation – and apply their share of the installation’s aggregated power generation to offset the cost of a similar amount of power on their electric bills.

The Clermont project was developed by Hudson Solar, a company based in Rhinebeck that has been developing and installing residential and commercial solar systems for 15 years. The project also was partially supported through a $65,000 grant from NY-Sun, a $1 billion state initiative aimed at expanding the use of solar energy. It is the 13th community solar project in the state and the first in Columbia County.

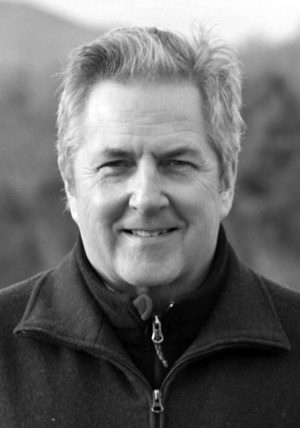

Jeff Irish, the president and founder of Hudson Solar, said community solar offers a way for people to benefit from green energy even if it isn’t feasible to install solar panels at their own home.

Jeff Irish, the president and founder of Hudson Solar, said community solar offers a way for people to benefit from green energy even if it isn’t feasible to install solar panels at their own home.

“Over the years, as many as three-quarters of the people who have approached us with an interest in solar energy have been unable to set up panels on their own property,” Irish said.

He explained that there are a variety of reasons why it may be impractical to install on-site solar panels at a home or business. A location may have too many trees, surrounding structures, or other physical features that limit exposure to sunlight. A particular home’s roof may not be large or strong enough to support solar panels, or the owners may dislike the visual appearance of the panels.

In addition, renters normally don’t have the option to install their own solar panels, but they can buy into a community solar project.

“Community solar gives more of these people access to panels at remote sites with optimal exposure to sunlight,” Irish explained.

The new solar installation in Clermont occupies a 1-acre field and has the capacity for 630 individual solar panels – enough to power up to 40 homes.

Irish said that by the beginning of February, 92 percent of the project’s available panels had been sold to 33 households – at a cost of about $750 per panel after tax rebates and other incentives.

States push clean energy

In the scheme of the overall energy system, community solar projects function in much the same way as individually owned panels. The electricity generated by each solar array is fed into the power grid, and the panels’ owners receive offset credits for the electricity they produce, thereby reducing their electric bills.

Community solar takes many forms, and is known by other names including “shared solar” and “roofless solar.” Variations of the idea may be oriented more toward businesses, homeowners or a mix.

The basic concept emerged around 2007 in Colorado. It was spurred in part by development of software that makes it more feasible to track the output and distribution of energy produced by multi-user solar facilities -- and to handle the billing and credits to individual users.

Interest and participation in community solar projects has gained momentum in recent years, with a boost from policies, regulations and incentives of the federal government and an increasing number of states, including Massachusetts, New York and Vermont.

Community solar in New York is part of a larger strategy initiated by Gov. Andrew Cuomo to increase the use of renewable energy. The state has set a goal of obtaining 50 percent of its electricity from solar and other renewable sources by 2030.

Alicia Barton, the president and chief executive of the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, hailed the Clermont project in a press release as evidence that “New Yorkers across the state are embracing our state’s transition to a clean energy future.”

Massachusetts adopted policies about five years ago to encourage what it calls “shared community solar” projects.

“All of the different states’ programs have similar basic goals, but each has a unique flavor in terms of specific policies and incentives,” explained Seth Ginsberg, president of Apis Energy Group, a solar developer based in Great Barrington.

There are several shared solar facilities already online in Berkshire County.

Variations on a theme

Community solar projects have differing business models of ownership and management, including co-operatives and direct ownership of panels by individual users. In other models, a developer or primary sponsor retains ownership and manages the facility. Some projects offer the option to rent panels or shares of the facilities.

“The specific model for a project is based on a combination of what is allowed by state policies and a business decision by a developer of what makes the most sense technically and financially,” Ginsberg explained.

The Clermont facility uses a model of direct ownership of individual panels by participants. It is focused on residential users, and it is similar to a condominium project in the sense that individuals buy a tangible property that is part of a larger complex.

Owners can transfer their account, and their energy credits, to a new home if they move within the same utility’s service area. They also have the right to sell or otherwise transfer ownership of their share of the solar installation if they move out of the service area, and they may choose to sell it for other reasons.

The Clermont facility uses a form of “net metering” in which credits to owners’ utility bills are based on a “100 percent retail offset” for 20 years. This effectively stabilizes the price of their power credits regardless of fluctuations in the price of electricity.

The power is provided on an aggregated basis to the utility. Each owner receives a credit on their bill that is based on the number of panels they own as a share of the overall power produced by the solar installation.

A state formula requires that each member buy a minimum of three panels but no more than the number needed to account for 100 percent of their average monthly power usage.

“The minimum of three panels is to avoid having too many individuals with small amounts of electricity generated, which would make the billing more complicated,” Irish explained. “The maximum number is to prevent people from buying up many panels and then reselling them at scalper prices.”

The portion of a household’s total energy bill that can be offset by solar-power generation varies based on each household’s consumption, but Irish estimated 15 to 19 panels would be needed to cover an average household’s total usage. The timeframe in which the savings on electricity bills starts to exceed the initial investment depends on the number of panels each person buys and how much power he uses. Irish said some people choose to buy a smaller number of panels, offsetting just a portion of their utility bill. Others who buy the equivalent of their total usage can eliminate the supply portion of their bill and pay only the utility’s monthly service fee.

Demand vs. legal limits

Hudson Solar worked with Clermont town officials to choose the site for the new installation. The town modified its zoning to allow this type of solar facility, with conditions that landscaping be used to limit the visual impact of the project.

Irish said his company plans to establish other shared solar facilities in the Capital District and Hudson Valley, although he wasn’t ready to disclose any specific locations.

“There is definitely a strong demand for community solar projects,” he said. “It makes a lot of sense and is good for the environment. It allows companies like Hudson Solar to serve the people who were unable to benefit from solar power before.”

But in New York and other states, the significant expansion of community solar faces a potential hurdle. To ensure that utilities are able to cover their expenses and generate a profit, many states have set caps on the amount of electricity from solar and other renewable sources that can be sent to the grid.

Because of the growing popularity of options such as community solar, these limits have been met or are being approached in many states. State officials now are having to reconcile their goal of boosting renewable energy production with utility companies’ financial needs.

Other factors may limit the rapid expansion of community solar. In Vermont, for example, some developers are concerned that new state siting standards for renewable-energy projects could make it more difficult to find locations for new solar installations.

And nationally, the Trump administration’s recent decision to impose import tariffs on solar equipment will raise the cost of many projects.

“There’s been a lot of give and take and adjustments of the policies and rules regarding solar power, and politics plays a role, which causes complications,” Ginsberg said. “It’s a challenge that we must figure out as a society.”

Nevertheless, Ginsberg said he sees community solar as another step in the evolution of solar power from its early incarnations -- as an expensive option with limited practical availability – to a more widespread, affordable and available option.

“Community shared solar is a social statement on the state level that says, ‘We want everyone to have access,’” he said. “It’s an equalizer for the middle class -- by enabling more people to benefit from solar power. The next round for it will be programs that also make it available to people in low-income housing, so that it eventually can be universally accessible.”