Arts & Culture December 2018 - January 2019

Celebrating light in a season of darkness

Exhibit explores traditions through artwork from children’s holiday books

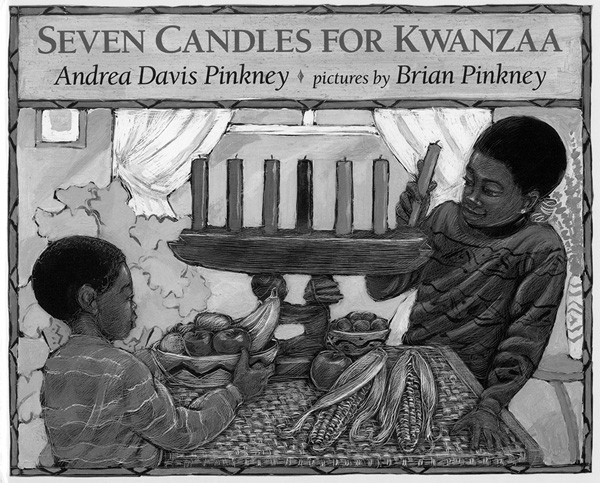

“Cultural Traditions: A Holiday Celebration,” now on exhibit at the Norman Rockwell Museum, includes Uri Shulevitz’s illustation from “Dusk” (2013), above, and Brian Pinkney’s images for the book “Seven Candles for Kwanzaa,” right. Courtesy Norman Rockwell Museum/Copyright Uri Shulevitz

“Cultural Traditions: A Holiday Celebration,” now on exhibit at the Norman Rockwell Museum, includes Uri Shulevitz’s illustation from “Dusk” (2013), above, and Brian Pinkney’s images for the book “Seven Candles for Kwanzaa,” right. Courtesy Norman Rockwell Museum/Copyright Uri Shulevitz

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

STOCKBRIDGE, Mass.

People sit knitting in rocking chairs, someone at the piano and someone playing guitar.

A woman on her way to college speaks a gorgeous poem of her own. People bring books and give readings: If they are working on a play or a song, they can try it out among friends.

Andrea Davis Pinkney remembers a family holiday with warmth and music and laughter.

Holidays connect to family, to birth and love and time, to the past and the future, and to the land. Across the country, as winter comes, families look to a stable in Bethlehem or the hills of Judea, and in Pinkney’s family a holiday reaches from California to a market in Ghana or a farm in Zanzibar.

She tells the story in “Seven Candles for Kwanzaa,” with artwork by her husband, Brian Pinkney.

This winter, a show at the Norman Rockwell Museum brings together illustrations from six well-loved books to reflect on winter holidays around the country and around the world.

“Cultural Traditions: A Holiday Celebration” opened last month and remains on view through Feb. 10, bringing together 40 works of art from six award-winning illustrators of children’s picture books.

The light that never goes out

The stories begin with the festival that will come first this year, and like every celebration in this show, it is a festival of light. Hanukkah opens on Dec. 2 and lasts for eight nights, until Dec. 10.

In Karla Gudeon’s paintings, families welcome eight nights in joyful color, as Harriet Ziefert tells the story in haiku of the candles in the menorahs, the music and games, letters on a dreidel, jelly doughnuts (sufganiyot), and potato pancakes (latkes) with applesauce.

Hanukkah looks back to a time when the kingdom of Judea came under a Greek leadership that suppressed Jewish worship. The Maccabees led a revolt and reclaimed their temple. And they rekindled a light in a lamp that should never go out.

In New England, the light comes aptly as the nights grow longer. It comes with light in the sky: In the Hebrew calendar, each new month begins with the new moon, and Hanukkah comes late in the month of Kislev, so it comes with the moon almost full. And each new day begins at sunset, when the first three stars appear.

Hanukkah has endured through dark times. In a companion exhibit, the museum will show K. Wendy Popp’s illustrations from “One Candle,” in which an American girl hears her grandmother and great aunt tell the story of a Hanukkah in Buchenwald. Taken from their families to the German concentration camp, hungry and afraid, they risked their lives to light a single flame with a dab of grease in a hollowed-out potato.

Uri Shulevitz also saw World War II. He was born in 1935 in Warsaw. “How I Learned Geography,” his Caldecott honor book, is based on his memories and tells the story of a boy whose family has had to flee their home country and live in poverty.

Here at the museum, in “Dusk,” another boy and his grandfather walk around a city at night, seeing the lights from many winter holiday celebrations.

They walk through the city as the lights come on — trees and Menorahs and Kwanzaa candles.

Shelter in the night

In the Southwest, the streets fill with candles.

Barbara Rundback, the assistant curator at the Norman Rockwell Museum who assembled this show, recalled seeing the candles when she was in Arizona: Everyone in town lights luminaries on their porches and along the walks in front of their houses to celebrate Las Posadas.

The name means “the Inns,” and in the Southwest, as well as in Mexico and Central and South America, in the nine days leading up to Christmas, actors re-create a journey from Nazareth to Bethlehem.

As Caldecott and Newberry award-winning writer and illustrator Tomie dePaola tells the story, Sister Angie is proud and delighted when her niece, Lupe, and Lupe’s husband are chosen to play Maria and Jose, the central roles. They practice as the town prepares for a community event.

Each year, pursued by masked devils and surrounded by music, Maria and Jose lead a procession, looking for a safe place to shelter for the night. When they find one, they will lead the neighborhood to celebrate with hot chocolate and pinatas.

Tonight, Lupe and her husband are stranded in deep snow, and a couple arrives out of the night with a burro to keep the tradition alive.

Christmas Eve

Not far away, a boy born on Dec. 25, 1948, in Orekhovo-Zuyevo, a small town near Moscow, meets a poem from the Taconic hills that has strongly influenced the story of Christmas in America.

Gennady Spirin now lives in New York, and with a classical Russian eye he illustrated, in 2006, the tradition Rundback herself remembers as a child. She and her family would hang up stockings and read aloud “The Night Before Christmas.”

Now the jolly old elf with his bag of toys feels like a legend to many families in America. But Rundback said the Santa Claus who climbs down the chimney and flies with his reindeer over the snow first appeared just a few miles away, in the Troy Sentinel, in 1823.

Santa Claus has a long history, but he has come in many forms. He takes his name from St. Nicholas, who left coins for the daughters of a poor widower in the stockings they had set out to dry -- and who lived on the southern Mediterranean coast of what is now Turkey.

Long before his day, Rundback said, Scandinavian children filled their shoes with hay, carrots and sugar for Odin’s horse, and he left gifts in exchange.

The tall, broad bearded man with a loud laugh and the colors of holly begins to take shape in a fictional history of “Dutch New York” by Washington Irving and in Charles Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol.” Rockwell’s father would read Dickens to him when he was a boy, Rundback said, and he would draw the characters.

Joy and beauty in the dark

Andrea Davis Pinkney and her husband draw on the experiences of their own family in the warm, bright scenes in “Seven Candles for Kwanzaa.”

“We have had many joyous celebrations,” Pinkney said by phone from New York, “and we wanted to share our celebration with a larger community.”

The book is an album of their holidays, she said, rooted in gatherings they have had and continue to have.

She has celebrated Kwanzaa as a child, and with her children and friends and family. When she was a girl, she said, after Christmas, the first thing they would do after the pumpkin pie was put away was to bring out the kinara, the holder for seven candles -- one black, three green and three red.

On Dec. 26, they would gather to light the black candle in the center, to celebrate the richness of many skin tones.

“Once it was lit, we knew Kwanzaa was here,” she said.

And they would sing together. One of her favorite songs, not a traditional Kwanzaa song but perfect for that feeling, was “This Little Light of Mine.”

“We would see that one candle burning,” she said, “and everyone knows the song.”

Kwanzaa is an American holiday, she said, inspired by African traditions.

Rundback explained that it rose out of the Freedom Movements of the 1960s. Maulana Karenga, a professor and chairman of black studies at California State University at Long Beach, created it and celebrated it with friends and family.

The name comes from the Swahili for first, and the date comes from the “first fruits” or harvest festivals that many African peoples and nations hold at this time of year, from Dec. 26 to Jan. 1.

“Kwanzaa is its own distinct celebration, as Hanukkah is,” Pinkney said. “It happens in the same season, but it’s not Christmas, it’s not New Year.”

Karenga wanted to join past and future, to reconnect with the traditions and the land that belonged to his ancestors in Africa.

“The beauty of the holiday is that it fuses those two cultural realities,” Pinkney said. “Part of our celebration is pouring libations, calling forth the wisdom of elders and introducing those traditions and stories with the youngest members of the family, bridging those generations.”

For the sake of the book, the Pinkneys traveled to West Africa, to Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, to Kumasi and Accra, and immersed in the colors and patterns of Kente cloth, a traditional weaving.

Seven days, seven themes

The holiday is rooted in seven days, seven candles and seven ideas, each named in the language of Swahili. The festival begins with “umoja,” or unity, like the voices laughing and singing around the table.

Each day the family lights one more candle and talks about the idea that belongs to that day. On the second day, they consider kujichagulia, or self-determination. It’s a day to learn traditions: Some families teach percussion or braiding hair in beautiful patterns, some of which women have handed down to their daughters for thousands of years.

“We think about something we really want to do in the new year,” Pinkney said. “We reflect on something we were determined to do, a creative project, a skill, dancing, a sport, cleaning out a closet.”

Pinkney’s husband reveals the story in warm scenes on scratchboard. The drawings are part of his kujichagulia, she said: “The work itself is percussive, rhythmic, and that’s what Kwanzaa is -- the color, the palette, so many hues and nuances of our heritage.”

On the third day, the family comes together for ujima, collective work.

“The principals sound so big, so lofty, so disciplined,” Pinkney said. “But it may mean we’re cleaning out this attic. We’re staining this rocking chair. You lay down the newspaper, and you pick the paint color, … get out the brushes, and we’ll get this done.”

The fourth day, in ujamaa, or cooperation, the family gets something to share, something they have all saved for and can use. And the fifth day is for nia, or purpose.

“We’re reflecting on the future,” Pinkney explained, “to do what makes us glad to be who we are.”

Gladness grows every day of the festival, in kuumba (creativity), as the family dances, rhymes, paints or plants seeds, and imani, the faith that good will happen. And on the seventh day, the week ends with karamu, a feast, a party with music and dancing.

When Pinkney was young, she said her family would write down the principles on paper, and have each guest draw one to talk about: “Niya, what was your purpose this year, what do you want to carry into the new year?”

On the last night they held, and still hold, a free salon.

“Bring an instrument, bring your voice, bring your knitting -- anything that sparks your creativity and that of others,” she explained.

They give gifts made by hand: a rag doll, a knitted sweater, a photo album.

“My husband’s sister, I call her my sister-in-love, is adept at crafting,” Pinkney said. “And she always would make dolls. … My kids would make collages.”

Kwanzaa has grown over the years, she said. She has seen the celebrations broaden from small gatherings, not widely known when she was a child, to full-out Kwanzaa parties.

“The doorbell is just ringing,” she said. “People keep coming, friends of friends of friends. We’re all one community.”

Dragons in the moonlight

And as the nights begin to grow shorter, a later winter festival comes back to a lunar calendar on the night of the new moon.

This celebration brings out the largest number of holiday travelers anywhere in the world, Rundback said, as people come together to welcome the Chinese New Year.

In Grace Lin’s “Bringing in the New Year,” another family celebrates as hers does in Somerville, Mass. They clean the house and make dumplings or spring rolls to welcome guests. They share steamed fish and noodles and prepare for the year ahead.

They hang spring couplets around the door -- welcoming words, something like the prayer or blessing, the Mezuzah, a Jewish family might set on a doorpost.

The festival of the Chinese New Year lasts 15 days, building up to fireworks and to lion and dragon dancers. And on the last day, families light rice paper lanterns to welcome the returning light of the moon, and of the sun.

The Norman Rockwell Museum will hold several events related to its “Cultural Traditions” exhibit, including three Family Day programs on Saturdays.

Brian Pinkney’s father, the Caldecott Award-winning illustrator Jerry Pinkney, will visit the museum from 1 to 4 p.m. Dec. 8, to share his illustrated stories of holiday wonder, warmth, and cheer, including “The Christmas Boot” by Lisa Wheeler, “The All-I-Ever-Want Christmas Doll” by Patrick McKissack and “A Home in the Barn” by Margaret Wise Brown.

K. Wendy Popp will share her Hanukkah story, “One Candle,” on Dec. 29, and Grace Lin will celebrate the Chinese New Year on Feb. 9.