Arts & Culture August 2018

Finding humor even in dark subjects

Two exhibits in Bennington gather the works of New Yorker cartoonists

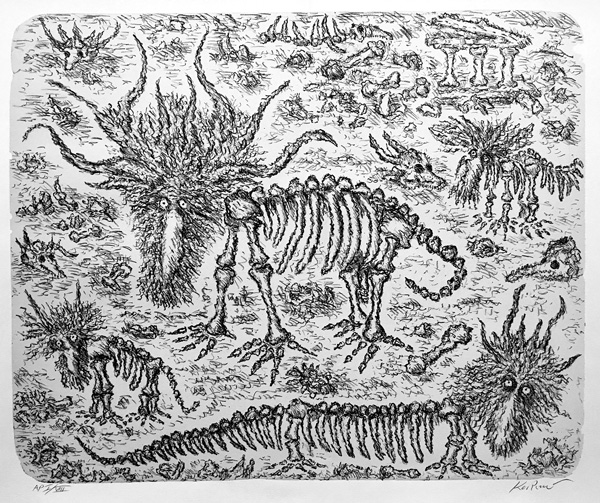

Curious skeletal creatures figure prominently in an exhibit of prints and drawings by Edward Koren that’s now on view at the Bennington Museum. Koren’s work is also included a separate show at the Laumeister Art Center that brings together works by 20 cartoonists for The New Yorker. Courtesy Bennington Museum

Curious skeletal creatures figure prominently in an exhibit of prints and drawings by Edward Koren that’s now on view at the Bennington Museum. Koren’s work is also included a separate show at the Laumeister Art Center that brings together works by 20 cartoonists for The New Yorker. Courtesy Bennington Museum

By KATE ABBOTT

Contributing writer

BENNINGTON, Vt.

In warm weather, Ed Koren sets up a print shop in his barn in Brookfield, Vt., and in the winter he draws.

He creates cartoons for The New Yorker and images for himself, like the bemused fossil creatures now on exhibit at the Bennington Museum. They’re skeletons with bright eyes that walk in a landscape of bones and stone pillars -- a rueful meditation on the end of a species.

The show, which opened last month and remains on view till Sept. 9, is entitled “Thinking About Extinction and Other Droll Things: Recent Prints and Drawings by Edward Koren.”

“The subject is morbid,” he said, “but the philosophy is a bit lighter and less satirical.”

A mile away, at the Laumeister Art Center, Koren’s work also appears in an exhibit of New Yorker cartoonists spanning half a century and more. In that show, created in memory of longtime New Yorker artist Jack Ziegler, Ziegler’s daughter Jessica has gathered 100 original drawings by 20 of the magazine’s cartoonists.

Among Koren’s drawings, in a sketch from 1984 two Triassic bird-crocodiles are dancing in top hats: “It looks like the ornithosuchians are attempting a comeback.”

“The plight of creatures and their lives and inner souls has always been of interest,” Koren said, sitting in the shade on the Bennington Museum’s terrace.

He has drawn more than 1,000 cartoons for The New Yorker across almost 60 years, playing a counterpoint between urban and natural ways of life.

As a boy, he was fascinated by the dioramas at the American Museum of Natural History, animals frozen in time.

“A lot of what I’ve done harks back to those early memories,” he said.

His recent focus on extinction came to him without design or forethought, he said. But it comes out of a lifetime of thinking -- 40 years of study, reading, listening to the news and being aware of climate science.

He recalls visiting the Gallery of Paleontology and Comparative Anatomy in Paris, which offers a procession of animals unclad by fur or skin, bills or feathers -- a huge family portrait of bones.

Over time, he has become more and more aware of debates about forces that may change the planet.

“We as a culture and as a planet have been talking about these things for a long time,” Koren said, “but not with the increasing urgency we’ve seen of late.”

Inspired by a colleague’s work

Koren said he has seen signs of the changing climate in the loss of songbirds in his Vermont village, the absence of moose in the high forest, earlier springs, later winters, endless rain and ice storms instead of snow, extreme weather patterns, drought.

And then he read Elizabeth Kolbert’s book “The Sixth Extinction,” for which she won the 2015 Pulitzer prize for general nonfiction.

“There have been five known disasters in the history of the planet,” he explained. “The sixth is ongoing and of our own making.”

Sometimes a mass extinction event is lightening-quick, like a meteorite in Chiapas. This one is moving at a pace humans can see.

“It’s happening in real time, and we’re not aware of it,” he said. “Like my creatures, my associates, surrogates, friends.”

Since reading Kolbert’s work, he said, he has felt her influence in his own. They are longtime colleagues in a sense; Kolbert lives in Williamstown, Mass., and she often writes for The New Yorker. But she and Koren are both freelance, working in their own studios.

As Koren started drawing creatures without skin or fur, he said, he felt in Kolbert’s writing a sense of species waiting out their demise, some adapting and some dying.

“She used the word marooned,” he said.

Some plants and animals have adjusted to changing conditions by moving. But a great many find themselves stranded, like the creatures in his new images. They don’t know what’s happening to them, but they have a dim awareness, a present inkling of something wrong.

“My creatures are versions of ourselves,” Koren said. “They’re my family, and by extension the larger family. Homo sapiens and the animal world are not very different.”

He alludes to past cultures in the backgrounds of his wry horned skeletons. Stone fragments and ruins lie among the bones. Former civilizations linger as dust in the desert.

Looking out at the Green Mountains, he quoted quietly from “Ozymandias,” Percy Bysshe

Shelley’s sonnet to a ruined monument in the desert:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

The words echo for him in this political moment -- “that arrogance, that sneering visage. How could this not have been written in the last two years?”

Koren said he feels the hubris in the stone king still around him, in political leaders and towns and people going on oblivious to the massive changes they all have a share in.

“We all feel that this will never touch us, ever,” Koren said. “It’s morbid and frightening … and kind of funny. And it’s the ultimate irony that we’re visiting this on our very selves.”

So his parched, wide-eyed fossils grow out of great respect and love for the natural world.

“It’s why I’m in Vermont, why living in an urban area doesn’t interest me as it once did,” he said. “I love cities and love to be in them, but I want to live close at hand to a different world.”

And from his foothold in the mountains, he turns over a difficult question: “Is there hope?”

Living close to the idea of extinction and recognizing seriously the dangers to the world, he may feel like a soldier in the trenches.

“The only way to get through it — they have to find something to laugh about at the very worst,” Koren explained.

And yet he looks out for signs that people acting together may still have an effect, and here and there he sees individual signs: more bear and loons in northern Vermont, breeding falcons -- kestrels.

“Here and there,” he said, “in conservation efforts, in idealistic, good people determined to reverse this, that’s where hope is.”

Some of Koren’s drawings invoke geological time in their making: At the Bennington Museum, five of them are lithographs, printed on a rare crystallized limestone, in a process largely untouched by time.

“It’s is a difficult medium to do right,” he said. “It demands a technical wizardry etching doesn’t, and it’s hard to control.”

Koren works with IDEM, a shop in Paris that makes artist prints in a form developed in the early 1800s. The shop worked with great artists of the early and mid-20th century: Marc Chagall, Picasso, Giacometti.

He said he was awestruck to see his own drawings on the same stone.

Works by 20 cartoonists

At the opening of the Bennington Museum show, Koren handed five cartoons to Eric Despard, the executive director and curator of the Laumeister Art Center, for that venue’s “Cartoons from The New Yorker” exhibit.

The show, which runs through Sept. 9, is the first major exhibition at the former Bennington Center for the Arts since it came into the hands of Southern Vermont College. The college took on the arts center as a gift last winter and opened softly in May, re-imagining the collection.

The summer show, Despard said, grew from a conversation with Jessica Ziegler, his friend for 30 years. Her father died in March 2017, after contributing to The New Yorker for more than four decades, and she wanted to honor him.

“She was on fire with the idea,” Despard said, and she began calling her father’s colleagues, inviting them in. She asked them each to send five of their favorite cartoons, and Despard recalled the excitement of seeing them come in by mail. Up close, he could see the detail and vibrancy of the original works, the textures of ink wash and white paint, white-out and glue and typesetting -- signs of the artists’ processes and the passing of time.

The show begins with original New Yorker covers from 1925 and 1926, the magazine’s first years in print, and the artwork spans half a century.

At the opening, Bob Mankoff, the magazine’s former cartoon editor, talked about choosing drawings for the magazine, looking through a thousand or more in a week. These are some of the few that stood out, for their sardonic insight into the way people live and survive, fool and reveal themselves. They see what crumbles and what lasts.

Henry Bliss sent images from the 1970s with a Charles Addams-like subtlety. A solar-powered Frankenstein lurches across a meadow. A father werewolf is putting his son to bed and softly reading aloud from “Hello Moon.” A bookstore’s “staff picks” shelf seems to have been stocked by Sweeney Todd and Edward Scissorhands.

In Tom Chitty’s more recent sketches, a robot incessantly checks his flower at the dinner table, and a Victorian couple takes a Daguerreotype-style selfie. Some artists refer to contemporary phenomena, but the ideas persist, and the humor stays fresh.

“People love it,” Despard said. “It’s the greatest joy to walk into these galleries and hear people belly laugh. And what I’m enjoying most is that everyone has their own cartoon, the one that resonates. And it’s always different.”