Arts & Culture February-March 2017

Sculptures that won’t sit still

Artist’s wooden figures mix puppetry, animation at Mass MoCA show

By JOHN SEVEN

By JOHN SEVEN

Contributing writer

NORTH ADAMS, Mass.

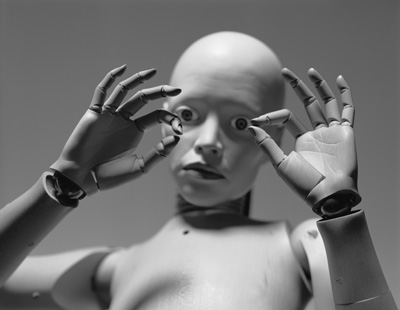

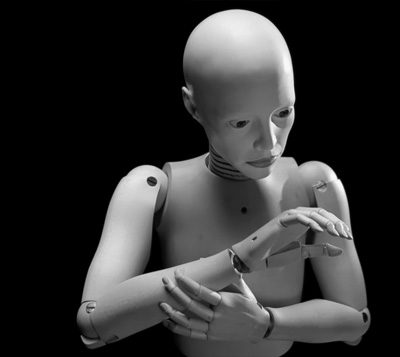

Works by the artist Elizabeth King, whose half-scale wooden figures are known for their uncannily human movements, are featured in a new show, “Radical Small,” that opens March 4 at Mass MoCA. Courtesy photos/Elizabeth King

With a new show at Mass MoCA, Elizabeth King is moving firmly along the path she started long ago.

Her work is neither sculpture nor puppetry, but somewhere in-between, with the end result often captured in elegant video animation by King.

The Virginia-based artist creates half-scale figures with features and movements that seem uncannily human. King’s show, “Radical Small,” opens March 4 at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art.

For King, there was no real transition from traditional sculpture to moveable figures. As a kid, she created puppets and marionette-like jointed figures.

Later, in art school, she incorporated these types of figures into her work, creating what she calls “metaphorical environments that the viewer could manipulate.” It was at that point that she began to study what would be considered the more traditional aspects of the history of sculpture, gaining an understanding of anatomy that she could apply to her work.

“Their emotional content came later, actually, as time went on, and are still very much developing now,” King said.

“Their emotional content came later, actually, as time went on, and are still very much developing now,” King said.

Sometime later, while living in New York City, King got a job restoring antique wooden mannequins, which had joints and could be posed. These began to inform the joint designs in her own figures, which she now creates entirely from her own specifications.

Most of her sculptures, whether complete figures or isolated body parts, now feature some aspect of movement, whether they are being moved in the presentation or are merely reliant on someone to do the moving for them.

King acknowledges that some of the intricacies of her joint design aren’t easy for viewers to access, but she said she tries to make as much of it viewable as possible.

“There’s enough open where you can look inside, you can look under, through openings in the head and see the mechanism for the movable eyes,” she explained. “Enough of that is glimpse-able that it gets you thinking about what is hidden inside our body in a metaphorical way.”

“I like this too,” King continued. “We don’t usually think about each other’s stomachs; we don’t think about each other’s circulatory systems when we meet. Yet we’re these churning little protoplasmic wonders churning around each other, and I’d love to think that the sculpture might remind us a little bit of all that is hidden that we don’t usually think about when we describe someone or talk about that personality or interact with them. Always at the same time there’s a terrifying piece of biology going on. Maybe only illness is a time when it comes up in a stark way for us, but I think art can remind us of it as well.”

Capturing expression, emotion

The heads of King’s figures are particularly striking for their detail and realism, the result of multiple processes by which King captures emotion, muscle tension and more.

She said that years ago, she would take life casts of her own head as well as her models’ in order to save hours of time that working from life would take.

“Things have to be three-dimensional from the get-go, so drawings will help a little bit, especially in designing with drawings,” she said. “But I always start with either a study in clay, a study in wax, a life cast in plaster, so that my studio is filled with life casts.”

King also focuses her creation of casts on particular parts of the head, which results in some odd displays in her studio.

“I’ll use my own mouth, because I’m available,” she said, to capture different expressions of the mouth. “And there will just be 20 mouths on little sticks doing different things. I have different castes of my nose, flared and unflared, forehead wrinkled and not wrinkled, and I’ll composite those together.”

The initial sculpture is done in clay over an armature using the casts or, sometimes, a mirror.

The initial sculpture is done in clay over an armature using the casts or, sometimes, a mirror.

“If it’s a portrait of a friend or relative, I’ll grab them for an hour,” King said. “Or I’ll work from memory, just because I stare at people a lot, and slowly I’ll put together a head that has a particular expression on it or that has some muscle tension on it.”

King then makes a plaster mold of the head and then a slip cast, which she fires several times, refines, fires again, and then she uses porcelain or sometimes bronze.

“I’ll take the head and put it on a body,” King said. “The bodies are all made of carved wood. The joints are wood on wood or, with some, the introduction of brass, hidden brass ball and socket joints. So I’m modeling clay, I’m machining brass, I’m carving wood. Those are probably the three main processes, but if there’s bronze involved, I’m also machining bronze and chasing it and finishing it. It’s all very hands-on work.”

King’s bodies are created from cut-up sculptures created from plaster casts, which she uses to figure out the specifics of where a joint will fit, how it will be specifically designed for that sculpture, and how she will join the joint with the figure. This care is taken because her goal, she says, is do more than just create a machine.

“I’m making compromises on both fronts, first in cutting a traditional statue up to animate it, joint it,” she said. “But then I’m making compromises in the anatomical side of things, because if I had full anatomical movement from mechanical joints, the thing would disintegrate; I’d lose all the sculpture’s emotional presence. So I’m always fighting to get these two different things to happen together.”

From pose to animation

In January, King was working on a small piece for the show in which the base of the thumb features a tiny spring-loaded, hidden joint in the wood – so that there is tension in the joint and the thumb is moved easily. She would follow variations of this pattern with the wrist and the elbow. This is all done with the next component of her work in mind: animation.

Ease of movement is crucial, which is why King’s figures are all small.

“You can’t animate with large pieces, because there is too much leverage and gravity and too many forces in play,” King explained. “So the scale was right -- it’s half life size. The weights and balances of the materials were right, and there was all this sensitive capability of moving parts of the anatomy that weren’t necessarily typical for and still aren’t typical for a lot of stop-frame models.”

King said she cheats a bit in creating movement in animation -- or the illusion of movement, as she point out -- including moving lights on the faces to optimize the facial expressions and complement the one moving part on the heads, the eyes.

She said animation changed her work, or at least the parameters that she worked within. Animation guides how and why she does certain things.

“Stop-frame animation was a moment of epiphany for me early in my life, she said. “And I’ve continued to love the sculptures as things in and of themselves and show them this way, posed, and then I have my other life, which is to animate them on film.”

Her first chance to pursue animation was in 1991, pre-computer, and since then she has used each experience to refine what she does sculpturally to make the animation more seamless.

“Even though the viewer doesn’t necessary encounter this directly, I still very much care about the character of the machinery, of the movement itself,” King said. “In other words, it’s not enough that it’s movable. I want to engineer it and build it so it’s elegantly movable, so you just touch it and move it a tiny degree and it stays there, and you don’t have to whip out a lot of Allen wrenches and screwdrivers.”

King is bringing this aspect of her work to the new show, at least for the first week, when she and animator Mike Belzer, well known for his work with Tim Burton and Henry Selick, will set up an animation studio in the gallery for the public to observe.

King has collaborated with Belzer before, on a film called “What Happened,” and this reunion features a special effort on the part of the museum to give them a flawless workspace that is open to anyone interested in seeing their process. Mass MoCA even built them a custom vibration-stage to allow them perfect stillness while they work.