Arts & Culture August 2016

Finding color and light in the Green Mountains

Modernist painter Milton Avery’s work in Vermont is focus of exhibit

By TELLY HALKIAS

By TELLY HALKIAS

Contributing Writer

BENNINGTON, Vt.

Milton Avery’s “Blue Trees” (1945) became one of his best-known paintings and was among those inspired by his visits to southern Vermont in the 1930s and ‘40s. It is featured in a new exhibit at the Bennington Museum. Collection Neuberger Museum of Art, Gift of Roy Neuberger, Purchase College, State University of New York. ©2016 The Milton Avery Trust/Artist Rights Society, New York.

Look at a Milton Avery painting and the first thing that will strike you is the extraordinary color.

Avery’s highly distinctive style is also known for its delicate balance between abstraction and representation.

And many of the traits of his work can be traced back to a time in the artist’s life when he spent summers with his family in Vermont.

Although he also vacationed in Canada and other places, and lived for many years in Connecticut before moving to New York City in 1925, Avery’s sojourns in Vermont proved to be pivotal in the development of the artist’s scope and vision.

Avery (1885-1965) is considered a master of Modernism, a kind of American version of Matisse. Artists of his caliber often seek destinations, whether physical or metaphorical, that are beyond the horizon.

His pilgrimages to Vermont began in the summer of 1935 and continued for many of the next eight years. The works resulting from, or influenced by, these treks are the theme for the Bennington Museum’s major exhibition of 2016, “Milton Avery’s Vermont.” The show, which opened last month, runs through Nov. 6.

The museum’s curator of collections, Jamie Franklin, said this is the first exhibition to take an intensive look at Avery based upon his summers spent in southern Vermont, mainly in the towns of Rawsonville and Jamaica.

“Avery regularly spent his summers traveling with his family in search of fresh subjects for his art,” Franklin said. “He was drawn to Vermont by his friend Meyer Schapiro, one of the most important art historians of the 20th century, who had owned a summer home here since 1930.”

Franklin said the exhibition studies Avery’s creative method and includes works such as pencil sketches drawn outdoors and subsequent works on paper, like watercolors made while in Vermont and based on those same sketches.

Inspired by Vermont landscapes

Franklin noted that all of Avery’s Vermont oil paintings were studio creations based on plein air sketches -- or on watercolors and gouaches that were executed in Vermont based on the outdoor sketches.

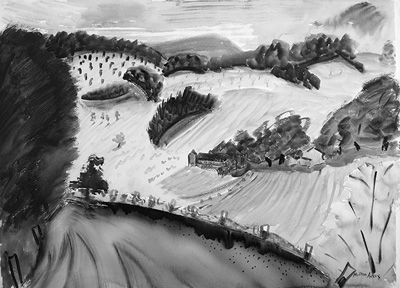

Avery’s “Untitled (Small Farm),” a watercolor from 1937, is among the works featured in “Milton Avery’s Vermont,” which runs through Nov. 6 at the Bennington Museum. Collection of the Milton and Sally Avery Art Foundation. Copyright 2016 The Milton Avery Trust/Artist Rights Society, New York.

One such work included in the exhibition is “Blue Trees,” which is among Avery’s best-known paintings. The artist rendered this 1945 painting of a forested and mountainous Vermont vista with both muted and vibrant uses of an unexpected hue.

In Vermont, Avery captured summer activities with family and friends and developed his highly personal response to the landscape in works characterized by bold, gestural marks and bright, non-associative colors.

Scholars and critics have noted the potential of “Blue Trees” to elicit a broad spectrum of reaction from any potential viewer. It’s in this way that Avery became recognized as an innovative, supreme colorist.

Robert Wolterstorff, an art historian who is the museum’s executive director, said the years Avery spent in Vermont were seminal to his maturity as an artist – and key to the public and critical recognition of his talent.

“Certainly, it is not exaggerating to say that Avery became the Avery we know and recognize during precisely the time he was coming to Vermont,” Wolterstorff said. “By the end of this period, he was on the threshold of acceptance as one of the American masters.”

Although Vermont helped in Avery’s breakthrough, the work he created here isn’t of interest merely because of what it led to, Wolterstorff added.

“These are glorious works in their own right, works to delight the eye and quicken the intellect,” he said.

During his time in Vermont, many subjects caught Avery’s attention. The presence of his family was key in providing character material – and in helping to foster a vibrant yet secure milieu in which the artist could thrive.

At her father’s side

Avery’s daughter, March Avery Cavanaugh, now 83, said she associates her childhood visits to southern Vermont with many simple pleasures.

“The first time I was only 4, and so I do not remember the painting process, only the interests of a child my age,” Cavanaugh said. “There was a cat we named Ginger, who we rented for the summer, and my 5-year-old birthday party, where we played ‘pin the tail on the donkey.’ Also, I cut my foot badly on a mowing machine.”

Cavanaugh, a well-regarded painter in her own right who watched intently as a child as her father painted, said she well remembers another visit to Vermont when she was 11.

Every day, she said, Avery would take her out to sketch in the morning. Although he encouraged his daughter to paint, Avery didn’t exactly offer lessons. He was, as she put it, “a very nonverbal painter.”

“I would show him one of my paintings, and all he would say was, ‘Paint another,’” Cavanaugh said. “The only advice I can remember him giving me was not to go to art school, and I didn’t. Of course, I learned a great deal from watching him paint. I only wish I had paid closer attention.”

In the afternoons, Avery would paint watercolors from the sketches, and then turn his attention to fun with the family.

“If the weather was good, we would go for a swim,” Cavanaugh said. “It was during the war, and food was in short supply. We ate a lot of Spam and traded blueberries we had picked with the local farmers for milk and eggs.”

Although Avery studied art and painted from an early age, he didn’t work full time as an artist until he was over 40, and it was many more years before his work gained widespread critical recognition.

Avery followed his own path and never gave in to popular trends, Franklin explained. As a result, after decades of focused work that yielded only moderate success, Avery gained acclaim in the American art world well after his most productive time in Vermont.

But those years in Vermont turned out to be key to the artist’s development, and the works he created here were part of the body of work that led to Avery’s wider recognition later in life.

“Avery’s Vermont sojourns proved to be a pivotal chapter in the development of the artist’s distinctive style,” Franklin said. “He captured summer activities with family and friends and developed his highly personal response to the landscape. This helps us appreciate more fully his rare contribution to the history of 20th century American painting.”

“Milton Avery’s Vermont” will run through Nov. 6 at the Bennington Museum, at 75 Main St. in Bennington. For more information, visit benningtonmuseum.org or call (802) 447-1571.