News

Buzz of the back yard

Beginner beekeepers find their sweet spot

By TELLY HALKIAS

By TELLY HALKIAS

Contributing writer

WILLIAMSTOWN, Mass.

When Alethea Morrison started her journey into the world of beekeeping five years ago, she and her husband kept a journal to document the experience.

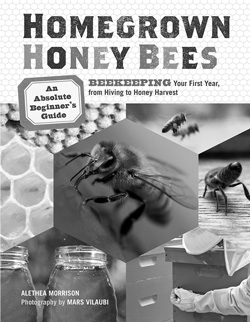

Last year, the journal became a book – “Homegrown Honey Bees: Beekeeping Your First Year, from Hiving to Honey Harvest” – put out by Storey Publishing of North Adams, where Morrison is creative director. Her husband, Mars Vilaubi, served as co-author and took photos for the primer.

The experiences of Morrison and Vilaubi – and the potential market for their book – reflect a growing trend around the region: More and more people are becoming backyard beekeepers.

For those who pursue beekeeping in a big way, there can be financial rewards. Honey prices have reached record highs nationally in each of the past two years, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture data.

But the vast majority of new beekeepers are hobbyists who simply want their own supply of fresh honey. For many, the hobby is an extension of their enthusiasm for locally grown foods, and some also are interested in the health benefits of bee products.

Morrison said she has a propensity for do-it-yourself projects, such as keeping chickens. Each project brings fulfillment and often leads to her next endeavor.

“There’s a joy to DIY, whether it’s growing your own food, building a bookcase, reupholstering a chair or knitting a scarf,” she said. “‘I love this,’ I said to myself. ‘What can I do to keep my DIY buzz on? Why, keep bees of course.’”

In their book, Morrison and Vilaubi record the events in their own hive and share the trials of their first year of beekeeping. The journal follows the couple from replacing a failing queen bee to supporting a colony over a harsh winter, as well as the reward of tasting their first harvest of honey.

Risks and rewards

As with any other activity, getting started often is a prospective beekeeper’s greatest challenge.

“I recommend that the beginner start with two or three hives,” Morrison said. “The startup costs are significant enough to merit budgeting for, but it requires very little once you’re under way. You’ll spend more than you would for a video game console -- and way more than you would for some knitting needles and a few skeins of yarn. But with those hobbies and most others, you have to feed the habit. Beekeeping is relatively self-sustaining.”

Morrison now has five hives in two separate locations. She said rookie beekeepers must invest financially in the hobby but will also be captivated in ways different than with other pastimes.

There are also risks. With pervasive pesticides, habitat destruction and invasive pests and diseases, it can be hard to keep honeybee colonies alive.

Despite this, Morrison added, it’s also a hobby full of surprises and discovery, and that is one of its appeals.

“I know people who have been keeping bees for 50 years, and every one of them will tell you that they are still learning,” she said. “One of the privileges of being a beekeeper is getting past surfaces and catching glimpses of a complicated, fascinating micro-society that is normally hidden from view. It would take more than a lifetime to understand all that is going on in there.”

Morrison said the principal factors behind a successful yield of honey are the health of the bees and the health of the plants surrounding the area of an apiary. A single hive might harvest anywhere from nothing to several hundred pounds.

“Many beekeepers support their hobby by selling honey,” she said. “But making a living from beekeeping is a long shot unless you have a major commercial operation providing pollination services to farms.”

Morrison recommends joining the closest beekeeping club or association and getting involved. She has taken her own advice: Morrison now serves as president of the Northern Berkshires Beekeeping Association.

“If you manage to score a bee mentor at a club meeting, you will double the fun of your first year of beekeeping,” Morrison said. “Don’t be shy. Beekeepers love what they do, and many of them are happy to share their wisdom with someone as ignorant but enthusiastic as you.”

Joining a movement

Across the New York state line in Hoosick Falls, Amanda Haar says she always supported local agriculture but never thought much about keeping bees until 2009, when she saw the chance to make a connection between the two.

At the time, a series of news stories detailed a sharp increase in the disappearance of honeybees elsewhere in the country because of what became known as “colony collapse disorder.” Scientists so far have not been able to definitively explain this phenomenon, but several studies have found that a class of widely used insecticides known as neonicotinoids may interfere with bees’ natural homing abilities, possibly preventing them from finding their way back to their hives.

There’s more than honey at stake in the loss of whole colonies of bees. Bees pollinate roughly 85 percent of the nation’s food crops, so without them, fruit trees, berry bushes and many vegetable plants would have much lower yields.

“I started beekeeping about five years ago in response to all the news about colony collapse,” Haar said. “We live in an agricultural community, and if you can, you should support farmers, and I saw keeping bees as a way of doing that.”

Haar said her family’s property includes many open fields and a good natural water source, so the decision to proceed was easy.

She said novice beekeepers should start simply, with a modest investment in equipment and bees, and with some hands-on education in advance.

“The first thing I did was read a few books on natural beekeeping,” Haar said. “I then took a one-day class in Manchester. That was extremely helpful, as it allowed me to ask all the questions I had. … There’s a lot of terminology associated with beekeeping that comes naturally to the experienced keeper but not so much to the novice. That’s important to know. The class clarified a lot for me.”

Haar then joined the Bennington Beekeepers Association. It typically meets once a month, at potluck dinners, for education and information sharing. The club has a nominal membership fee.

“As for other costs, the biggest cost is the hive itself,” Haar said. “You can buy them online or at a local beekeeping store, but either way they will set you back a couple hundred dollars. If you want to go the Williams-Sonoma route, that could approach $600.”

There are many components to a hive that aren’t apparent, but most of them are essential to successful beekeeping, she said. Basic requirements include a beekeeping hood and gloves, and possibly even a protective suit.

“Some old pros go gloveless, but I’m not that brave,” Haar said with a chuckle. “You also need some basic harvesting equipment plus whatever containers for bottling or storage. And, of course, you need bees.”

The cost for bees varies depending on whether a beginner procures them in a cage or a “nuke” or nucleus – a smaller honeybee colony created from a larger colony. That startup for the novice should always be undertaken with a good sense of seasonal timing.

“If you’re stocking your hive for the first time, get your bees in the early spring,” Haar said. “If you do it through a local supplier, place your order early, as they often sell out. Start calling around Thanksgiving to find out when they’re starting their order list. You can also try sourcing locally through beekeeping clubs.”

Going to commercial scale

Although Haar’s endeavor yields at best about 70 pounds of honey annually, which she consumes or gives away, other, larger family operations cross over into the commercial realm.

Regionally, one such enterprise in Vermont’s Champlain Valley is Heavenly Honey Apiary in Monkton, owned by Scott and Valarie Wilson. Established in 2007, it’s an operation known as a “sideliner,” meaning it produces honey for sale as well as for personal consumption.

“Valarie and I started with one hive, garnering about 40 pounds of honey that year,” Scott Wilson said. “At peak, which is August, a healthy hive will contain about 60,000 to 80,000 honeybees. Our second year, we grew to three hives; our third year, eight hives. Now we are up to about 30 hives.”

Valarie Wilson explained that not all hives produce honey, as some are the nucleus hives created during mid-summer – the source of bees Haar mentioned.

Nucleus hives are smaller, denser hives created by the beekeeper from an existing “strong hive” to replace the standard hives that die off during the winter. Creating nucleus hives is a method of increasing an apiary’s size and allows a beekeeper to increase the number of hives without having to buy more bees.

Because Scott Wilson has a full-time job, about 30 hives is the maximum amount the couple can currently manage well.

“The initial startup cost to purchase one beehive, the minimum needed tools and other gear, and bees, is about $500 to $600,” Valarie said.

Scott stressed the theme of education and the importance of guidance from experienced beekeepers.

“All new beekeepers should attend as many hands-on, in-person workshops as possible,” Scott said. “There is nothing on YouTube or in books that can come close to the value of in-hive workshops. The feel of the tools, the sounds and smells of the hive, sweat pouring down your forehead into your eyes, stings on the hands -- cannot be realized while sitting at a desk watching videos.”

Valarie added that theory is good, but she said the hive tells the story. So a beginner needs a mentor – ideally not just one but a few, she added.

“Crusty old beekeepers are awesome but sometimes biased in their own personal approaches,” she said. “A good cross-section of learning will help to develop the new beekeeper’s own individual approach and style.”